Sometimes I'll Google phrases like "best diverse comic books" and come across titles I've never heard of, such as this gem by Thi Bui, The Best We Could Do. Thi Bui was born in Vietnam and left the country with her family as a refugee during the war. They eventually made it to the United States, where Bui met her husband and they started a family. While raising her son, Bui reflected upon her relationships with her own parents and how little she knew about their lives before she entered the world. This graphic memoir is her attempt to tell their story and her own, and it's a beautiful one.

As I get older, it becomes more and more clear to me that my parents are human, and that they are humans who age. As I see my friends with their (still quite young) children, I can also see just how exhausting parenthood can be. There are few relationships in life that can remain as inherently selfish and self-absorbed as that of a child towards its parent. Even now, as an adult who is capable of doing adult things like cooking her own dinner and doing her own laundry, every time I go to my parents' house, I regress 100% and expect there to be food waiting for me when I arrive, and food ready for me to take back with me when I leave. I call my dad and complain of medical symptoms so that he will call in prescriptions for me. I call my mom and ask if she'll come over to oversee work on my house so that I don't have to take a day off of work.

Bui reflects upon this as she takes care of her son and compares her childhood to those of her parents' and her son's. Her parents came of age in vastly different circumstances; they met in college, got married, and then their world imploded. They raised children in the midst of war, and then left the country on a boat (while Bui's mother was eight months pregnant) to get to Malaysia. They arrived in America, still chased by their personal demons, and raised a family the best way they knew how. Bui struggled with her relationship with her parents, particularly her father, and only began to understand why when she learned more about their childhoods. The empathy that comes through in the way she describes her family history is so moving, and the title of the book works so well. Her parents weren't perfect, and they made mistakes. But they did the best they could do, and their children grew up with better lives, and their grandchildren grow up with even better ones.

The Best We Could Do is a beautiful story, particularly at this time when so much of the world is turning away refugees. Accepting refugees not only changes the lives of the refugees, but of generations to come. The book is also a truly heartfelt memoir about family and the deep love that you can have for people you don't always understand and who are far from perfect.

Showing posts with label far east. Show all posts

Showing posts with label far east. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 5, 2017

Monday, May 4, 2015

Meet Balsa, your new hero

Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit, by Nahoko Uehashi, is the first book in a ten-book series of which I was completely unaware. It's set in a fantasy version of medieval Japan and centers on this amazing woman, Balsa, who is the greatest martial artist ever and who works as a bodyguard. Her new charge is Prince Chagum, who has been possessed by a spirit. He is being pursued by people who want to kill him and by some sort of animal who wants to eat the spirit inside him.

I am not sure how I first heard about this book, but I assume it was on a blog somewhere. I thought it was a graphic novel, but it's not, though there is gorgeous artwork on not just the cover but throughout the story. I also don't think I realized it was just the first in a long series, of which only the first two books have been translated into English. Hopefully the rest are translated soon!

There were a lot of things I really enjoyed about this story. First, it's a fantasy adventure series that features a woman as the hero, which is awesome. Balsa is an amazing fighter who possibly enjoys fighting a little bit too much. She has a slight romantic interest, and that man is a healer who waits patiently for her to return to him, another great example of role reversal. A third very powerful character is an old woman. Again - how awesome is this cast of characters? I love the way Uehashi took what is a fairly common plot - a strong, weary person promised to help a smaller, weaker, but important person to safety - and twisted all of it around to give women and men roles they normally wouldn't get in a fantasy novel.

I also LOVED the setting. Loved, loved, loved. Everything felt so real, from the heavy snow in the mountains to the simple recipes. And the way the characters interacted with each other based on class and role was so different than anything I had come across before. It was excellent. Uehashi wrote a novel for children and young adults but within these pages lies a lot of commentary - how facts can be embellished or erased; the power of folklore and stories; and the importance of understanding the truth, and not just listening to what people tell you.

That said, the book was not without its flaws. The story did not flow very smoothly. There were multiple worlds existing in the same space, which is a complicated idea to describe, and I don't know if the translator did Uehashi justice. The description of the spirit (actually an egg) that lived inside Chagum and the animal that wanted to eat the egg were also very odd. There were several disparate parts that were all supposed to come cleanly together at the end, but instead, it felt like cutting and pasting and the result was a little haphazard. Hopefully the second book is better translated and easier to follow.

BUT, seriously, this book is less than 250 pages with big font and I read it on a rainy afternoon and evening. The negatives above are, in my opinion, outweighed by the characters and the unique setting. Check it out!

I am not sure how I first heard about this book, but I assume it was on a blog somewhere. I thought it was a graphic novel, but it's not, though there is gorgeous artwork on not just the cover but throughout the story. I also don't think I realized it was just the first in a long series, of which only the first two books have been translated into English. Hopefully the rest are translated soon!

There were a lot of things I really enjoyed about this story. First, it's a fantasy adventure series that features a woman as the hero, which is awesome. Balsa is an amazing fighter who possibly enjoys fighting a little bit too much. She has a slight romantic interest, and that man is a healer who waits patiently for her to return to him, another great example of role reversal. A third very powerful character is an old woman. Again - how awesome is this cast of characters? I love the way Uehashi took what is a fairly common plot - a strong, weary person promised to help a smaller, weaker, but important person to safety - and twisted all of it around to give women and men roles they normally wouldn't get in a fantasy novel.

I also LOVED the setting. Loved, loved, loved. Everything felt so real, from the heavy snow in the mountains to the simple recipes. And the way the characters interacted with each other based on class and role was so different than anything I had come across before. It was excellent. Uehashi wrote a novel for children and young adults but within these pages lies a lot of commentary - how facts can be embellished or erased; the power of folklore and stories; and the importance of understanding the truth, and not just listening to what people tell you.

That said, the book was not without its flaws. The story did not flow very smoothly. There were multiple worlds existing in the same space, which is a complicated idea to describe, and I don't know if the translator did Uehashi justice. The description of the spirit (actually an egg) that lived inside Chagum and the animal that wanted to eat the egg were also very odd. There were several disparate parts that were all supposed to come cleanly together at the end, but instead, it felt like cutting and pasting and the result was a little haphazard. Hopefully the second book is better translated and easier to follow.

BUT, seriously, this book is less than 250 pages with big font and I read it on a rainy afternoon and evening. The negatives above are, in my opinion, outweighed by the characters and the unique setting. Check it out!

Monday, February 16, 2015

A Septuagenarian Crime-Solving Boss in Communist Laos

The Coroner's Lunch, by Colin Cotterill, is one of those books that makes me feel better about my TBR pile. I've had it for a few years now and only just got around to reading it, mainly because I felt guilty at hardly reading anything from my own shelves in 2014. But it waited patiently for me to finally get around to it, and then it validated the space it takes up on my shelf by being just fantastic. Hooray!

The Coroner's Lunch introduces us to Dr. Siri, a 72-year-old coroner in Laos around 1970, just as the country adjusts to Communist rule. As coroner, Siri must write cause of death for many cadavers, and some of the people who come to him do not seem to have died natural deaths. Even when he is heavily advised against doing so, Siri investigates those deaths. Sometimes he is helped along by the spirit world; though he is a very logical and pragmatic man, Dr. Siri often sees the spirits of the dead, and they will often guide his research and methods.

I was a little skeptical when I first encountered the spirits in The Coroner's Lunch, mostly because I didn't really like a somewhat similar theme in Maisie Dobbs. But it was very believable here and works seamlessly into the story as a whole. Dr. Siri has a lot of demons and guilt, and in many ways, the spirits are just manifestations of those occurrences in his past. But in other ways, the spirit world is alive and well and a very strong theme in this story, so if that puts you off, you may want to steer clear. For my part, I loved the angle that brought to this book, especially when weighed against Siri's own skepticism. It added a new, unique dimension to the whole thing.

I also really appreciated the setting. I don't know of many books set in Laos (do you?). I liked that it was set in the 1970s, just after the Communist revolution as the country was on the cusp of modernity but still quite rural. For example, Siri first used a telephone at age 72. But he also goes to a rural area and sees massive deforestation, so clearly the modern world, with its benefits and horrors, hasn't left Laos behind. The secondary characters are all wonderful, too. I particularly liked Thuy, Dr. Siri's very capable female assistant who also enjoys reading comic books.

And Siri himself is absolutely charming. I really enjoy books with older protagonists, and Dr. Siri is like a Miss Marple who has decided that she doesn't care who she pisses off, she's just going to go do her thing and be a boss. To clarify, Miss Marple totally IS a boss, but she hides it very well behind her politeness and gentle kindness. Dr. Siri, like the honey badger, doesn't care who he offends because he's old and tired and just wants to solve crime and get on with it. He's fantastic.

The author of the Dr. Siri series is Colin Cotterill, a British expat living in Southeast Asia. I suspect Cotterill has the dry sense of humor the Brits are famous for, and he has infused Dr. Siri with that humor as well (though maybe the Lao are more witty and dry than I give them credit for - I don't know much about their humor). In my head, I imagined Dr. Siri to be very similar to Bill Nighy in Worricker, except not British. This was probably helped along by the audiobook narrator, Clive Chafer, who was absolutely excellent but extremely English.

I thoroughly enjoyed this novel, and I'm so glad that someone (I don't remember who it was!) recommended it to me in a comment on this blog or in response to a comment I made elsewhere. This is exactly the sort of mystery I love, that deals with not just the mystery at hand, but with so many other things as well, with characters with whom I can't wait to spend more time.

The Coroner's Lunch introduces us to Dr. Siri, a 72-year-old coroner in Laos around 1970, just as the country adjusts to Communist rule. As coroner, Siri must write cause of death for many cadavers, and some of the people who come to him do not seem to have died natural deaths. Even when he is heavily advised against doing so, Siri investigates those deaths. Sometimes he is helped along by the spirit world; though he is a very logical and pragmatic man, Dr. Siri often sees the spirits of the dead, and they will often guide his research and methods.

I was a little skeptical when I first encountered the spirits in The Coroner's Lunch, mostly because I didn't really like a somewhat similar theme in Maisie Dobbs. But it was very believable here and works seamlessly into the story as a whole. Dr. Siri has a lot of demons and guilt, and in many ways, the spirits are just manifestations of those occurrences in his past. But in other ways, the spirit world is alive and well and a very strong theme in this story, so if that puts you off, you may want to steer clear. For my part, I loved the angle that brought to this book, especially when weighed against Siri's own skepticism. It added a new, unique dimension to the whole thing.

I also really appreciated the setting. I don't know of many books set in Laos (do you?). I liked that it was set in the 1970s, just after the Communist revolution as the country was on the cusp of modernity but still quite rural. For example, Siri first used a telephone at age 72. But he also goes to a rural area and sees massive deforestation, so clearly the modern world, with its benefits and horrors, hasn't left Laos behind. The secondary characters are all wonderful, too. I particularly liked Thuy, Dr. Siri's very capable female assistant who also enjoys reading comic books.

And Siri himself is absolutely charming. I really enjoy books with older protagonists, and Dr. Siri is like a Miss Marple who has decided that she doesn't care who she pisses off, she's just going to go do her thing and be a boss. To clarify, Miss Marple totally IS a boss, but she hides it very well behind her politeness and gentle kindness. Dr. Siri, like the honey badger, doesn't care who he offends because he's old and tired and just wants to solve crime and get on with it. He's fantastic.

The author of the Dr. Siri series is Colin Cotterill, a British expat living in Southeast Asia. I suspect Cotterill has the dry sense of humor the Brits are famous for, and he has infused Dr. Siri with that humor as well (though maybe the Lao are more witty and dry than I give them credit for - I don't know much about their humor). In my head, I imagined Dr. Siri to be very similar to Bill Nighy in Worricker, except not British. This was probably helped along by the audiobook narrator, Clive Chafer, who was absolutely excellent but extremely English.

I thoroughly enjoyed this novel, and I'm so glad that someone (I don't remember who it was!) recommended it to me in a comment on this blog or in response to a comment I made elsewhere. This is exactly the sort of mystery I love, that deals with not just the mystery at hand, but with so many other things as well, with characters with whom I can't wait to spend more time.

Thursday, January 15, 2015

Non-Humans of New York

Hele Wecker's The Golem and the (D)Jinni is set mostly in Manhattan, right at the turn of the 20th century. The two main characters are Chava, a golem, and Ahmad, a jinn. Chava was created to be the wife of a man who died on their voyage to the new world. Ahmad has no idea how he ended up in Manhattan - his last memory is from about 1000 years ago. In contrast, Chava's first memory is of waking up on the ship and meeting her (ill-fated) husband.

Ahmad and Chava both stumble through their new lives in New York, trying to understand humankind - the relationships that form between people, the decisions they make, how they treat each other, who has responsibility for what actions. They also, serendipitously, meet each other one evening, and embark upon a friendship that helps both of them understand their place in the world and deal with the consequences of their natures and decisions.

I found several things very interesting about this book. I'm a sucker for any story with mythology or folklore or mysticism, and this book is full of all those things. For that reason alone, I wanted to read the book. But there was more! For example, I really liked the way Wecker played out the tension between each character's true nature - for Chava, to solve everyone's problems, for Ahmad, to disregard everyone's problems - and their attempts to fit into human civilization. Chava, for example, is terrified that one day, her true nature will come out and she will beat everyone around her to a bloody pulp because that's what golems do when they are threatened. In conrast, Ahmad thinks humans over-complicate everything, and people should just do what feels good and damn the consequences.

In that way, Chava and Ahmad play out traditional gender roles even though they are not human. Ahmad toys with plenty of women, and they are the ones who have to wake up in the morning, bereft, while he just moves onto the next person. But it's not that Ahmad doesn't care about those women; it's that humankind fascinates him, and he needs to understand the whole species, not just one person. And so he moves on. Chava's whole purpose in existing, on the other hand, is to do what other people tell her to do. In fact, they don't even have to tell her, they just have to think it and she'll know. She is therefore very eager to please and worries constantly about whether she did the right thing.

Though the main characters were pretty fascinating on their own, I think there were far too many secondary characters who didn't really progress the story that much. There's a bored, rich girl (doesn't every book set in early 20th century America require one of those?). There's a curious Bedouin girl. A cursed ice cream seller. A lonely, quiet boy. A lonely, quiet man. A concerned father. A creepy old man. A creepy middle-aged man. A kind middle-aged woman. And more, and more. We get back stories on several of these characters. And, in general, I enjoyed these back stories, but I don't think they were necessary. The two title characters in the novel don't even meet until 1/3rd of the way through the book (what is this, Anna Karenina?). And while I enjoy a good, atmospheric, meandering story, this one just felt weighted down by all those characters.

That said, it's a great story to read on a cold, damp night!

Ahmad and Chava both stumble through their new lives in New York, trying to understand humankind - the relationships that form between people, the decisions they make, how they treat each other, who has responsibility for what actions. They also, serendipitously, meet each other one evening, and embark upon a friendship that helps both of them understand their place in the world and deal with the consequences of their natures and decisions.

I found several things very interesting about this book. I'm a sucker for any story with mythology or folklore or mysticism, and this book is full of all those things. For that reason alone, I wanted to read the book. But there was more! For example, I really liked the way Wecker played out the tension between each character's true nature - for Chava, to solve everyone's problems, for Ahmad, to disregard everyone's problems - and their attempts to fit into human civilization. Chava, for example, is terrified that one day, her true nature will come out and she will beat everyone around her to a bloody pulp because that's what golems do when they are threatened. In conrast, Ahmad thinks humans over-complicate everything, and people should just do what feels good and damn the consequences.

In that way, Chava and Ahmad play out traditional gender roles even though they are not human. Ahmad toys with plenty of women, and they are the ones who have to wake up in the morning, bereft, while he just moves onto the next person. But it's not that Ahmad doesn't care about those women; it's that humankind fascinates him, and he needs to understand the whole species, not just one person. And so he moves on. Chava's whole purpose in existing, on the other hand, is to do what other people tell her to do. In fact, they don't even have to tell her, they just have to think it and she'll know. She is therefore very eager to please and worries constantly about whether she did the right thing.

Though the main characters were pretty fascinating on their own, I think there were far too many secondary characters who didn't really progress the story that much. There's a bored, rich girl (doesn't every book set in early 20th century America require one of those?). There's a curious Bedouin girl. A cursed ice cream seller. A lonely, quiet boy. A lonely, quiet man. A concerned father. A creepy old man. A creepy middle-aged man. A kind middle-aged woman. And more, and more. We get back stories on several of these characters. And, in general, I enjoyed these back stories, but I don't think they were necessary. The two title characters in the novel don't even meet until 1/3rd of the way through the book (what is this, Anna Karenina?). And while I enjoy a good, atmospheric, meandering story, this one just felt weighted down by all those characters.

That said, it's a great story to read on a cold, damp night!

Monday, December 29, 2014

Review-itas: Closing out 2014

Haruki Murakami is one of those authors that both intrigues and intimidates me. The second book I read by him is one of his earlier collections of short stories, After the Quake, set in the months following the earthquake that shook Japan in 1995.

Murakami's stories always feel so ephemeral to me. There is an other-worldly, dream-like quality to them that I can't quite grasp. Only hours after finishing the book, I often can't remember what the stories were, though I remember the atmosphere of the whole collection. I enjoyed After the Quake much more than I did The Elephant Vanishes. Here, the characters are grappling with a huge and horrific event, so there isn't the same "meh" attitude towards life that pervaded The Elephant Vanishes.

The stories all center on characters who look back over their lives and try to understand when they were derailed, what defines them. And often, they find that they've allowed themselves to be defined by other people or things that they don't like thinking about. My personal favorite story was about a woman in Thailand who learns how to let go of the past so that she can move forward. A simple lesson that shows up again and again in literature, but Murakami gives it a true touch of grace.

Cory Doctorow's In Real Life was much less successful for me. There are a few positive points. The main character, Anda, is a kind, shy, and slightly overweight girl who really comes into her own and gains confidence through online gaming. And the artwork is really beautiful - Wang did a brilliant job in the way she used color. But the premise of the story really bothered me.

There's not much I can say about this book that isn't already covered in The Book Smugglers' fantastic and thorough commentary, so I will direct you all there with this nugget to entice you to click through:

Almost immediately after finishing Lev Grossman's The Magicians, I went on to read its sequel, The Magician King. I liked this one much more than the first book, though there was a scene towards the end that I found very disturbing. The main character, Quentin, wasn't quite as insufferable in this book because he became aware of what a jerk he can be and seemed to take steps to remedy the situation a bit.

The Magician King maintains the humor and appreciation for the absurd that the first book featured, which I really liked. And the audiobook narrator, Mark Bramhall, is pretty brilliant. I think he's a significant part of why I continue with these books. And people tell me that the last book in the trilogy, The Magician's Land, is the best of the bunch, so I am in line to get that one on audiobook, too. Hopefully it just continues to get better and better!

Murakami's stories always feel so ephemeral to me. There is an other-worldly, dream-like quality to them that I can't quite grasp. Only hours after finishing the book, I often can't remember what the stories were, though I remember the atmosphere of the whole collection. I enjoyed After the Quake much more than I did The Elephant Vanishes. Here, the characters are grappling with a huge and horrific event, so there isn't the same "meh" attitude towards life that pervaded The Elephant Vanishes.

The stories all center on characters who look back over their lives and try to understand when they were derailed, what defines them. And often, they find that they've allowed themselves to be defined by other people or things that they don't like thinking about. My personal favorite story was about a woman in Thailand who learns how to let go of the past so that she can move forward. A simple lesson that shows up again and again in literature, but Murakami gives it a true touch of grace.

Cory Doctorow's In Real Life was much less successful for me. There are a few positive points. The main character, Anda, is a kind, shy, and slightly overweight girl who really comes into her own and gains confidence through online gaming. And the artwork is really beautiful - Wang did a brilliant job in the way she used color. But the premise of the story really bothered me.

There's not much I can say about this book that isn't already covered in The Book Smugglers' fantastic and thorough commentary, so I will direct you all there with this nugget to entice you to click through:

I felt utterly uncomfortable (to put it very mildly) about the depiction of the Chinese characters’ plight and the lack of viewpoint from their perspective – the stress on Anda’s feelings rather than Raymond’s about his own situation is problematic to the extreme and reeks, REEKS of white saviour complex and American superiority (cue me rolling my eyes when Anda was all horrified at the lack of proper health insurance in China when in America things are not exactly rainbows and ponies, are they.)

Almost immediately after finishing Lev Grossman's The Magicians, I went on to read its sequel, The Magician King. I liked this one much more than the first book, though there was a scene towards the end that I found very disturbing. The main character, Quentin, wasn't quite as insufferable in this book because he became aware of what a jerk he can be and seemed to take steps to remedy the situation a bit.

The Magician King maintains the humor and appreciation for the absurd that the first book featured, which I really liked. And the audiobook narrator, Mark Bramhall, is pretty brilliant. I think he's a significant part of why I continue with these books. And people tell me that the last book in the trilogy, The Magician's Land, is the best of the bunch, so I am in line to get that one on audiobook, too. Hopefully it just continues to get better and better!

Monday, June 9, 2014

The future, Asian style

I first heard about Aliette de Bodard's novella On a Red Station, Drifting on Stainless Steel Droppings. I wanted the book as soon as I read Carl's review and promptly went over to Amazon to purchase it. So I hope you read his review, too, and that it has the same effect on you as it did on me. I don't read much science fiction, so I thought a novella written from an Asian female perspective was just the thing to get me to dip my toes into the genre:

For generations Prosper Station has thrived under the guidance of its Honoured Ancestress: born of a human womb, the station’s artificial intelligence has offered guidance and protection to its human relatives.

But war has come to the Dai Viet Empire. Prosper’s brightest minds have been called away to defend the Emperor; and a flood of disorientated refugees strain the station’s resources. As deprivations cause the station’s ordinary life to unravel, uncovering old grudges and tearing apart the decimated family, Station Mistress Quyen and the Honoured Ancestress struggle to keep their relatives united and safe. What Quyen does not know is that the Honoured Ancestress herself is faltering, her mind eaten away by a disease that seems to have no cure; and that the future of the station itself might hang in the balance…

There was a lot that felt unfamiliar to me about this book. I don't read a lot of science fiction, so already I felt a bit out of my depth right from the start, with all the action taking place on space stations and distant planets. I also don't know a lot about Vietnamese culture, and therefore wasn't always sure if I was a little lost because I didn't understand the culture or the setting. Regardless, I was a little lost :-)

But I expected to feel a little lost in reading a new genre, and I didn't mind very much. There was a lot that felt familiar, too, for those that know the fantasy and science fiction genres well - a once-prosperous place now fallen on hard times with a large population and limited resources. Failing infrastructure. A long, never-ending war that has taken away the heroes and left the defenseless alone. You know the story, right? But that's where de Bodard takes off into the awesomeness of a feminine perspective and an East Asian influence.

But I expected to feel a little lost in reading a new genre, and I didn't mind very much. There was a lot that felt familiar, too, for those that know the fantasy and science fiction genres well - a once-prosperous place now fallen on hard times with a large population and limited resources. Failing infrastructure. A long, never-ending war that has taken away the heroes and left the defenseless alone. You know the story, right? But that's where de Bodard takes off into the awesomeness of a feminine perspective and an East Asian influence.

It is so rare (really, ridiculously rare) to see a woman's perspective in fantasy and science fiction, and even more abysmally rare to see the perspective of someone of color. It was so refreshing to read this book, with its two central characters both women, and neither of them with a romantic interest or "God, I wish I was prettier" thought in their heads for the whole book! Rather, both women were concerned about their friends and family and their ways of life. You know. Things that normal people care about. And, much like in real life, there is no villain in this story. There are just people with different perspectives who misunderstand each other and want different things.

And the Vietnamese perspective was so great, too. On a Red Station, Drifting gave me such a zing of excitement because it is such a wonderful example of all that fantasy and science fiction can and should be. It provides such a unique lens on the traditional hero story, one that includes things that are so important in Eastern cultures: respecting your elders, ancestor worship, and strong family ties. de Bodard brings these themes into her novella so seamlessly that you can easily imagine a future in which Eastern culture dominates, and see just what the positives and negatives of such a culture would be.

I'm pretty impressed that de Bodard was able to pack so much punch into such a short novel. Clocking in at just over 100 pages, On a Red Station, Drifting is not a huge commitment and therefore is an excellent introduction to the science fiction genre. It's also a lovely reminder of how many different ways there are to tell a story, ways that are influenced by culture, history, gender, religion, and different ways of viewing the world. Highly recommended.

Monday, April 28, 2014

Love and espionage in North Korea

Adam Johnson's The Orphan Master's Son is a novel set in North Korea. After reading several non-fiction books about life in North Korea, I have become completely fascinated with the country and how people make their lives there. Johnson's novel brings a new take on that country to life - it is about the people there who know that their Dear Leader is a corrupt liar, but do their best to improve their lives and those of their loved ones.

Jun Do grew up in labor camps and then became a kidnapper, stealing people from their lives in Japan to become teachers, singers or other workers in Korea. He's good at his job and rises through the ranks quickly, shedding previous versions of himself so that no one ever really knows who he is. As he gets closer and closer to the Dear Leader's inner circle, he wants more and more desperately to get out and to get his family out, but struggles to find a way to do so without endangering everyone.

The narrative of this story was difficult for me to follow sometimes, probably because I was reading it on audiobook. The perspective would shift from one character to another, and the timeline would move back and forth and characters would change facts to tell a story that was far more likely to get them off lightly than to tell the truth. Usually, this would involve triple rainbows in celebration of North Korea, or about starving Americans being helped by beneficent Koreans. While I enjoyed the audiobook version, I think I would recommend this one to be read in written form to decrease the amount of confusion (though it seems like people who read it in print also struggled with the shifts).

There was a lot of brutality and propaganda and unhappiness in this book. It was tough to read. But I really appreciated Johnson's humanization of all his characters. Jun Do does horrible things, but he also inspires trust and loyalty in the people who are closest to him. He tries his best to stick to a moral code in a country where there really is no moral ground, just whatever the state decrees. It's easy to think about North Koreans always turning each other in and reporting each other's activities to authorities and living completely paranoid lives. But within that system, friendship and love and loyalty do still exist, and Johnson brought that very much to life.

I also liked how Johnson brought some humor into this book, though it was a bit of bleak humor. The second half of the book has three narrators: Jun Do, his interrogator, and the North Korean radio broadcast. All three of them are ostensibly telling the same story, but they tell it in completely different ways. It's fascinating to see how the interrogator draws conclusions based on what he has been told and what he's found out, and how that stacks up against what Jun Do really did, and how all of this is warped into a story by North Korean radio to either laud or revile the parties included, depending on how the government wants to sway things.

I think sometimes my confusion over the timeline and narrators kept me from loving this book as some others did. While I liked Jun Do, I didn't really care for any of the other characters. And the narrators in the book are quite unemotional. Which I think is the point - I get the impression that North Korea is not a country known for excessive emotion - but it made the book a little monotone.

However, there are only so many books on North Korea out there! And this one definitely brings nuance and breaks new ground.

Jun Do grew up in labor camps and then became a kidnapper, stealing people from their lives in Japan to become teachers, singers or other workers in Korea. He's good at his job and rises through the ranks quickly, shedding previous versions of himself so that no one ever really knows who he is. As he gets closer and closer to the Dear Leader's inner circle, he wants more and more desperately to get out and to get his family out, but struggles to find a way to do so without endangering everyone.

The narrative of this story was difficult for me to follow sometimes, probably because I was reading it on audiobook. The perspective would shift from one character to another, and the timeline would move back and forth and characters would change facts to tell a story that was far more likely to get them off lightly than to tell the truth. Usually, this would involve triple rainbows in celebration of North Korea, or about starving Americans being helped by beneficent Koreans. While I enjoyed the audiobook version, I think I would recommend this one to be read in written form to decrease the amount of confusion (though it seems like people who read it in print also struggled with the shifts).

There was a lot of brutality and propaganda and unhappiness in this book. It was tough to read. But I really appreciated Johnson's humanization of all his characters. Jun Do does horrible things, but he also inspires trust and loyalty in the people who are closest to him. He tries his best to stick to a moral code in a country where there really is no moral ground, just whatever the state decrees. It's easy to think about North Koreans always turning each other in and reporting each other's activities to authorities and living completely paranoid lives. But within that system, friendship and love and loyalty do still exist, and Johnson brought that very much to life.

I also liked how Johnson brought some humor into this book, though it was a bit of bleak humor. The second half of the book has three narrators: Jun Do, his interrogator, and the North Korean radio broadcast. All three of them are ostensibly telling the same story, but they tell it in completely different ways. It's fascinating to see how the interrogator draws conclusions based on what he has been told and what he's found out, and how that stacks up against what Jun Do really did, and how all of this is warped into a story by North Korean radio to either laud or revile the parties included, depending on how the government wants to sway things.

I think sometimes my confusion over the timeline and narrators kept me from loving this book as some others did. While I liked Jun Do, I didn't really care for any of the other characters. And the narrators in the book are quite unemotional. Which I think is the point - I get the impression that North Korea is not a country known for excessive emotion - but it made the book a little monotone.

However, there are only so many books on North Korea out there! And this one definitely brings nuance and breaks new ground.

Thursday, April 17, 2014

Two sides of the same coin

Gene Luen Yang's companion graphic novels, Boxers and Saints, got a lot of attention a few months ago when they came out. I finally got them in at the library and promptly read them in what I feel was probably the wrong order. I read Saints first because it arrived first. But after finishing both books and seeing the covers linked above, I understand why the series is called Boxers & Saints, rather than Saints & Boxers because there was a lot more alluding to Saints in Boxers than there was the other way around.

I feel like that paragraph was probably really difficult to understand if you haven't read the books. So, moving on.

Boxers & Saints is a graphic novel set in China during the Boxer Rebellion. The context of the story is that there are many Europeans who are flooding into China, bringing their foreign culture and ways and religions with them. This wreaks havoc on the Chinese population, some of whom convert to Christianity and appreciate the foreign goods, and some of whom think the Europeans are ruining their way of life. Yang's story tells the history from both points of view. Little Bao suffers firsthand from the British invasion; his father is beaten and never quite recovers. On the other hand, Four Girl never found a place for herself at home as she was considered bad luck. So she escaped to the church and made a home for herself there.

I really like the idea behind these novels. In history, there aren't many facts, just opinions that are voiced more loudly than others. And even stark facts hide so much nuance and gray areas. I love that Yang tackled this head-on by showing two people on opposite sides who were likable and easy to empathize with. I also like that he showed the damage done by both sides. There were a lot of things that led up to the Boxer Rebellion, but the outcome was a lot of pain and fear and loss on all sides. Yang does not sugarcoat that reality at all.

I also think Yang did wonderfully with his use of color in the stories. Four Girl's story was told in black and white, maybe with some sepia thrown in. And Joan of Arc in bright yellow. Little Bao's was a riot of color in contrast, with bold, vivid frames really bringing his story to life. And the facial expressions that Yang can portray in his drawings are exquisite - you can definitely see exactly what each character is feeling!

I didn't love either of these books, though. Overall, I enjoyed Boxers more than Saints, but I found both books a little lacking. In Saints, for example, Four Girl didn't represent the Christian side well to me at all. She basically just wanted cookies, so she started talking to a Christian. And then her family kicked her out of the house, so she joined the church. And then she didn't really believe in the Christian God or do anything that made herself stand out to me as someone worthy of a story. She had visions of Joan of Arc, but I don't think there was much of a strong correlation between Joan and Four Girl.

In Boxers, Little Bao had a much stronger character. His motivations in joining the Boxers were understandable, and I empathized with the difficulties he faced as a leader. Overall, I found his story much better developed and interesting than Four Girl's.

I'm really glad I read these books because I have been interested in them since they came out. What a fantastic and creative way to tell one story through different lenses. I think we should all try to learn history this way - by reading accounts from different sides and learning what motivated and drove people to act as they did. While I didn't love the stories themselves, I really applaud the effort and hope that Yang does more like this, or inspires other authors to do the same. So many historical events that I would love to see put in context! Such as:

I feel like that paragraph was probably really difficult to understand if you haven't read the books. So, moving on.

Boxers & Saints is a graphic novel set in China during the Boxer Rebellion. The context of the story is that there are many Europeans who are flooding into China, bringing their foreign culture and ways and religions with them. This wreaks havoc on the Chinese population, some of whom convert to Christianity and appreciate the foreign goods, and some of whom think the Europeans are ruining their way of life. Yang's story tells the history from both points of view. Little Bao suffers firsthand from the British invasion; his father is beaten and never quite recovers. On the other hand, Four Girl never found a place for herself at home as she was considered bad luck. So she escaped to the church and made a home for herself there.

I really like the idea behind these novels. In history, there aren't many facts, just opinions that are voiced more loudly than others. And even stark facts hide so much nuance and gray areas. I love that Yang tackled this head-on by showing two people on opposite sides who were likable and easy to empathize with. I also like that he showed the damage done by both sides. There were a lot of things that led up to the Boxer Rebellion, but the outcome was a lot of pain and fear and loss on all sides. Yang does not sugarcoat that reality at all.

I also think Yang did wonderfully with his use of color in the stories. Four Girl's story was told in black and white, maybe with some sepia thrown in. And Joan of Arc in bright yellow. Little Bao's was a riot of color in contrast, with bold, vivid frames really bringing his story to life. And the facial expressions that Yang can portray in his drawings are exquisite - you can definitely see exactly what each character is feeling!

I didn't love either of these books, though. Overall, I enjoyed Boxers more than Saints, but I found both books a little lacking. In Saints, for example, Four Girl didn't represent the Christian side well to me at all. She basically just wanted cookies, so she started talking to a Christian. And then her family kicked her out of the house, so she joined the church. And then she didn't really believe in the Christian God or do anything that made herself stand out to me as someone worthy of a story. She had visions of Joan of Arc, but I don't think there was much of a strong correlation between Joan and Four Girl.

In Boxers, Little Bao had a much stronger character. His motivations in joining the Boxers were understandable, and I empathized with the difficulties he faced as a leader. Overall, I found his story much better developed and interesting than Four Girl's.

I'm really glad I read these books because I have been interested in them since they came out. What a fantastic and creative way to tell one story through different lenses. I think we should all try to learn history this way - by reading accounts from different sides and learning what motivated and drove people to act as they did. While I didn't love the stories themselves, I really applaud the effort and hope that Yang does more like this, or inspires other authors to do the same. So many historical events that I would love to see put in context! Such as:

- The American Civil War

- Partition in India/Pakistan

- Arab Spring

What events would you like to see brought to life in this manner?

Thursday, January 9, 2014

The idyllic life of rural Malaysia

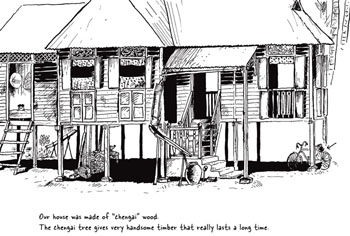

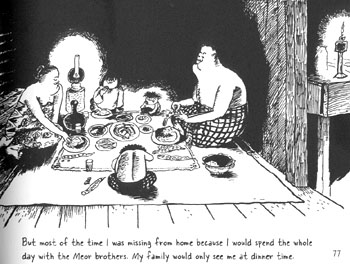

Kampung Boy is a graphic novel I found while browsing the shelves of the library one day. It caught my eye as it's about growing up in very small village in Malaysia and the author, Lat, is apparently one of Malaysia's best-loved comic artists. This was enough to pull me in - I know nothing about life in Malaysia - and I settled in to a very happy hour reading about Lat's life.

The artwork in this book really matches the tone of the story. It's light, episodic, and sweet, and the black and white images really lend themselves to bringing this to life.

Lat tells readers about everything from going fishing in the river to getting circumcised. And his descriptions of his family members, while only telling us what is necessary for that particular story, make those characters come to life. Helped, of course, by the illustrations.

There are hints of developments that reminded me of a very different book, 1493, as Lat described how much of the land around his kampung was being developed into rubber tree plantations. There is also a large tin factory nearby, so life probably isn't as quiet as Lat's pictures make it out to be.

It's a very quick read, but no less enjoyable because of it, and I hope that I can find the sequel, in which Lat goes off to school in a bigger city. I can see why this artist is so popular in his home country, and I'm glad that the book version of his comics is available for us in the West now, as he really is great fun.

The artwork in this book really matches the tone of the story. It's light, episodic, and sweet, and the black and white images really lend themselves to bringing this to life.

Lat tells readers about everything from going fishing in the river to getting circumcised. And his descriptions of his family members, while only telling us what is necessary for that particular story, make those characters come to life. Helped, of course, by the illustrations.

There are hints of developments that reminded me of a very different book, 1493, as Lat described how much of the land around his kampung was being developed into rubber tree plantations. There is also a large tin factory nearby, so life probably isn't as quiet as Lat's pictures make it out to be.

It's a very quick read, but no less enjoyable because of it, and I hope that I can find the sequel, in which Lat goes off to school in a bigger city. I can see why this artist is so popular in his home country, and I'm glad that the book version of his comics is available for us in the West now, as he really is great fun.

Monday, January 6, 2014

The beachcomber's guide to turning back time

Ruth Ozeki's A Tale for the Time Being is one of those books that kept popping up for me all over the internet. All the reviews I saw were positive, so I decided that I wanted to read it even though I had only a very vague idea of what the book was about. It recently came available from the library on digital download and I listened to it all last week on my commute. Ozeki herself narrates the novel, and she is really good.

Both Jenny and Vasilly read and loved this book (if that isn't enough to induce you to read it, then I wash my hands of you), but like me, they struggled to describe the plot in a way that will make you run out to the store or library or internet and grab it immediately. The story revolves around two women. Nao Yasutani is a teenager who grew up in California and then moved back with her parents to Japan. She struggles in school, is constantly bullied by her peers, and has a lot of difficulties at home, too, where she deals with a suicidal father. She gets through her days with the help of her great-grandmother, a Buddhist nun who always knows just what to say and do. Ruth is a middle-aged author who lives on a remote Canadian island. One day, she finds Nao's diary washed up on the shore of the beach in a trash bag. As she reads Nao's journal, she becomes obsessed with finding out more about Nao and helping the young girl through her difficult life.

See? Reading the above summary does not make me want to read the book and I already read and loved it. So perhaps it's best to go into this novel as I did, with just a vague idea of the plot and the knowledge that people who read the book REALLY REALLY loved it.

Nao Yasutani is one of the most charismatic and engaging narrators I have come across in a long time. She struggles through so many horrible things but her voice is always so spot-on and real and perfect, I just fell in love with her. I can completely understand why Ruth felt so invested in her story; I felt invested in it, too.

There is so much in this book besides Nao's scary life and Ruth's isolated one. There is philosophical discussion, a lot of information about crows, a whole bunch of tear-jerking moments about the strong bonds between different family members (particularly between a girl and her father), how difficult it can be to deal with a crisis of conscience, and so much more. Ozeki also does something similar to G. Willow Wilson in the way they approach time and how we control time, but I think Ozeki's method was easier for me to understand than the one Wilson used in Alif the Unseen.

There are so many lovely, beautiful messages in this book and they are not at all preachy, which is a small issue I had with the other book I read by Ozeki, My Year of Meats. This one, I had no issues with. The whole story is a delight and I was utterly enchanted. The little twist of magical realism at the end was welcome, too. I suppose some people may find it odd, but I thought it was perfect and it fit so well within the story.

Truly a wonderful book to help close out 2013. Highly recommended.

Both Jenny and Vasilly read and loved this book (if that isn't enough to induce you to read it, then I wash my hands of you), but like me, they struggled to describe the plot in a way that will make you run out to the store or library or internet and grab it immediately. The story revolves around two women. Nao Yasutani is a teenager who grew up in California and then moved back with her parents to Japan. She struggles in school, is constantly bullied by her peers, and has a lot of difficulties at home, too, where she deals with a suicidal father. She gets through her days with the help of her great-grandmother, a Buddhist nun who always knows just what to say and do. Ruth is a middle-aged author who lives on a remote Canadian island. One day, she finds Nao's diary washed up on the shore of the beach in a trash bag. As she reads Nao's journal, she becomes obsessed with finding out more about Nao and helping the young girl through her difficult life.

See? Reading the above summary does not make me want to read the book and I already read and loved it. So perhaps it's best to go into this novel as I did, with just a vague idea of the plot and the knowledge that people who read the book REALLY REALLY loved it.

Nao Yasutani is one of the most charismatic and engaging narrators I have come across in a long time. She struggles through so many horrible things but her voice is always so spot-on and real and perfect, I just fell in love with her. I can completely understand why Ruth felt so invested in her story; I felt invested in it, too.

There is so much in this book besides Nao's scary life and Ruth's isolated one. There is philosophical discussion, a lot of information about crows, a whole bunch of tear-jerking moments about the strong bonds between different family members (particularly between a girl and her father), how difficult it can be to deal with a crisis of conscience, and so much more. Ozeki also does something similar to G. Willow Wilson in the way they approach time and how we control time, but I think Ozeki's method was easier for me to understand than the one Wilson used in Alif the Unseen.

There are so many lovely, beautiful messages in this book and they are not at all preachy, which is a small issue I had with the other book I read by Ozeki, My Year of Meats. This one, I had no issues with. The whole story is a delight and I was utterly enchanted. The little twist of magical realism at the end was welcome, too. I suppose some people may find it odd, but I thought it was perfect and it fit so well within the story.

Truly a wonderful book to help close out 2013. Highly recommended.

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Sticking out like a sore thumb

Shenzhen is the third graphic travel memoir I've read by Guy Delisle, and I think I may give up on him now. I just feel like he's not a very positive person (though he describes himself as an optimist in the book), and his unhappiness when he travels really seeps through the pages of his books. I enjoyed Burma Chronicles, but I thought he was kind of a jerk in Pyongyang. In Shenzhen, he's not really a jerk, but he just seems so unhappy to be in Shenzhen that I'm surprised he decided to write a book about his time there. So much of the time, he talks about wanting to leave the city and visit Hong Kong and Canton. In fact, a good portion of the book is not about Shenzhen at all but about Delisle's weekend trips away.

And he says he likes Hong Kong because he blends in there.

I can imagine how exhausting it must be to spend months in a place where you are made to feel so completely different than everyone else. To not speak the language means that you really are quite isolated and can't make friends or go many places on your own. It's also hard to be the one white person in a sea of Asians (I assume), especially when people stare and point and all the rest that comes with the territory.

But at the same time, Delisle could have used the opportunity to talk about that, rather than just saying he enjoyed Hong Kong because he could read the language and it felt more European. That made him seem like the sort of person who only wants to go to western Europe on trips, and I know that's not true as he's spent a significant amount of time in Asia. I just wish his desire to learn about other cultures and immerse himself in a different lifestyle would come out more in his books.

That may not be what he wants to do, though. Delisle's strength is in his humorous anecdotes, his ability to take a small occasion and find the universality that exists there. He talks about how scared he was to ride a bike in Shenzhen, but then tells readers what the correct technique is (basically - just go forward with confidence and people will have to let you in). He talks about someone he works with telling a joke that was a huge hit with the office, but when Delisle asks someone to translate it for him, it makes no sense. But he laughs heartily, anyway. These moments really are fun to read about because I think all of us have been in that situation before, feeling very much away from home. But I think I would have appreciated those vignettes more if they hadn't been surrounded by commentary about Delisle not liking Shenzhen much at all.

And he says he likes Hong Kong because he blends in there.

I can imagine how exhausting it must be to spend months in a place where you are made to feel so completely different than everyone else. To not speak the language means that you really are quite isolated and can't make friends or go many places on your own. It's also hard to be the one white person in a sea of Asians (I assume), especially when people stare and point and all the rest that comes with the territory.

But at the same time, Delisle could have used the opportunity to talk about that, rather than just saying he enjoyed Hong Kong because he could read the language and it felt more European. That made him seem like the sort of person who only wants to go to western Europe on trips, and I know that's not true as he's spent a significant amount of time in Asia. I just wish his desire to learn about other cultures and immerse himself in a different lifestyle would come out more in his books.

That may not be what he wants to do, though. Delisle's strength is in his humorous anecdotes, his ability to take a small occasion and find the universality that exists there. He talks about how scared he was to ride a bike in Shenzhen, but then tells readers what the correct technique is (basically - just go forward with confidence and people will have to let you in). He talks about someone he works with telling a joke that was a huge hit with the office, but when Delisle asks someone to translate it for him, it makes no sense. But he laughs heartily, anyway. These moments really are fun to read about because I think all of us have been in that situation before, feeling very much away from home. But I think I would have appreciated those vignettes more if they hadn't been surrounded by commentary about Delisle not liking Shenzhen much at all.

Labels:

20th century,

biography,

far east,

graphic novel,

travel

Monday, August 26, 2013

Tales of a dancing dwarf, a disappearing elephant, and a green monster

Why didn't I realize that Haruki Murakami was so quirky? Now that I look at the book summaries of many of his books, I see that quirkiness (or some synonym of that word) shows up in every single description. So why I didn't expect it, I don't know. But listening to Murakami's short story collection The Elephant Vanishes while driving to and from work was an absolutely surreal experience. You'd be in a story with someone who appears totally normal, making spaghetti or drinking a beer or listening to classical music, and then BAM! you're introduced to some little green monster or a dancing elf or a man who works in a vanishing elephant. And then it's gone and you return to normalcy and you are not quite sure if what you heard really happened or was some bizarre dream-memory in your mind. It reminded me a lot of The Invisible Man, particularly the part in which the narrator worked at a paint factory and then underwent crazy treatments. None of which were ever referenced again, so that when my teacher asked us in class about the paint factory part of the book, we were all like, "WHOA, that really happened?!"

That pretty much sums up how I felt about a lot of the stories in this book - like I was off-kilter and not sure if what I was listening to was really happening. For me, this feeling worked well in a series of short stories. Part of the reason is because some of the stories did not have the magical realism, surrealism element to them. Part of the reason is that every character had this detached narrative style, so it seemed much more real because they themselves believed in what was happening so fully.

That pretty much sums up how I felt about a lot of the stories in this book - like I was off-kilter and not sure if what I was listening to was really happening. For me, this feeling worked well in a series of short stories. Part of the reason is because some of the stories did not have the magical realism, surrealism element to them. Part of the reason is that every character had this detached narrative style, so it seemed much more real because they themselves believed in what was happening so fully.

Monday, August 5, 2013

And I thought life was hard as a MIDDLE child...

The Third Son, by Julie Wu, is populated by characters who are completely extreme. The main character, Saburo, is an extremely neglected child. His lady love, Yoshiko, is an extremely ambitious person. His parents are extremely strict and harsh. His older brother is extremely cruel. His cousin is extremely kind. The Americans are extremely wishy-washy.

The cover is extremely pretty.

I really did not enjoy this book. I don't know too much about Taiwanese culture, but if Julie Wu is correct, then third sons are so little loved that their parents can pretty much starve them so that they need to get injections due to severe malnutrition. Even when the family is wealthy. First sons get everything, and everyone else must fend for themselves. Poor Saburo never even got an egg. They all went to his extremely cruel older brother.

The Third Son begins in Taiwan during World War II. Saburo is a young boy trying to escape an air raid, and he runs into a beautiful girl while trying to escape and hide. The two of them have a moment. Then the beautiful girl, Yoshiko, walks away, and Saburo goes back to his miserable existence. But he never forgets Yoshiko. He thinks about her as he gets expelled from school, thinks about going to but then never applies to college in the US, and pretty much any other time. Then he meets her again, but his extremely cruel older brother is interested in her, too. So Saburo has to find a way to win her back.

I think there were many reasons this book just fell flat for me. First, I didn't really care much about Saburo or Yoshiko. I guess they were nice people, but Saburo was just really whiny and Yoshiko wasn't even in the book for most of the time. So I didn't really believe in this huge, epic love story between them because - well - I couldn't really see what there was to like in each other. And everyone else in the book, too, was just so exhausting to read about. I mean, seriously, Saburo's parents were just SO MEAN. And I didn't understand why, if they were so wealthy, they wouldn't just buy enough food to feed their whole family instead of only getting enough for themselves and their eldest son and not giving enough to everyone else. I don't think I fully understand just how the cultural norms worked. And even if a culture generally favors an eldest son, I don't think that means that they despised their other children, but that's what this book made it seem like, and it was hard to read.

To me, the most valuable aspect of this book was the insight it provided into life in Taiwan in the mid-20th century. I didn't really know anything about the Japanese occupation and then the transfer of power to China, and then the crazy political machinations between different Chinese parties, becoming more and more paranoid. It was good to learn more about it, and I appreciate Wu for shedding light on a topic that we in the West don't hear much about.

Note: I received a complimentary copy of this book to review.

The cover is extremely pretty.

I really did not enjoy this book. I don't know too much about Taiwanese culture, but if Julie Wu is correct, then third sons are so little loved that their parents can pretty much starve them so that they need to get injections due to severe malnutrition. Even when the family is wealthy. First sons get everything, and everyone else must fend for themselves. Poor Saburo never even got an egg. They all went to his extremely cruel older brother.

The Third Son begins in Taiwan during World War II. Saburo is a young boy trying to escape an air raid, and he runs into a beautiful girl while trying to escape and hide. The two of them have a moment. Then the beautiful girl, Yoshiko, walks away, and Saburo goes back to his miserable existence. But he never forgets Yoshiko. He thinks about her as he gets expelled from school, thinks about going to but then never applies to college in the US, and pretty much any other time. Then he meets her again, but his extremely cruel older brother is interested in her, too. So Saburo has to find a way to win her back.

I think there were many reasons this book just fell flat for me. First, I didn't really care much about Saburo or Yoshiko. I guess they were nice people, but Saburo was just really whiny and Yoshiko wasn't even in the book for most of the time. So I didn't really believe in this huge, epic love story between them because - well - I couldn't really see what there was to like in each other. And everyone else in the book, too, was just so exhausting to read about. I mean, seriously, Saburo's parents were just SO MEAN. And I didn't understand why, if they were so wealthy, they wouldn't just buy enough food to feed their whole family instead of only getting enough for themselves and their eldest son and not giving enough to everyone else. I don't think I fully understand just how the cultural norms worked. And even if a culture generally favors an eldest son, I don't think that means that they despised their other children, but that's what this book made it seem like, and it was hard to read.

To me, the most valuable aspect of this book was the insight it provided into life in Taiwan in the mid-20th century. I didn't really know anything about the Japanese occupation and then the transfer of power to China, and then the crazy political machinations between different Chinese parties, becoming more and more paranoid. It was good to learn more about it, and I appreciate Wu for shedding light on a topic that we in the West don't hear much about.

Note: I received a complimentary copy of this book to review.

Labels:

#diversiverse,

20th century,

america,

asia,

family,

far east,

historical fiction,

war

Thursday, July 25, 2013

The Khmer Rouge, through the eyes of a child

In the Shadow of the Banyan was a book that I stupidly chose to read in fairly public places - on planes, trains, and buses. This was not a great decision because it's very difficult to read this book with dry eyes. It's also very hard not to continue reading this book once you've started, and so I just tried to sniffle very quietly and discreetly into my tissues and everyone around me politely pretended not to notice.

In the Shadow of the Banyan, by Vaddey Ratner, is set during the Cambodian civil war of the 1970s. We first meet our narrator, Raami, living a charmed life as a royal princess on an idyllic estate in Phnon Penh. But very quickly, revolution comes and Raami's family must leave their home to go become workers in the country. This is especially difficult for Raami as she suffered from polio as a baby and has difficulty walking. It's also difficult for her royal father, who believes in the ideals of the revolution but must hide his identity for his family's safety. He makes a sacrifice that most can't understand and that his family finds it difficult to forget. As Raami is shuffled from one place to another, connecting with some people and completely dissociating herself from others, working long, hard hours and slowly starving, we see the Cambodian civil war in all its terrible reality, and learn the power that stories can have to lift us away from our lives.

I cannot believe that this is Ratner's first novel, and in her second language, no less. The writing was absolutely stunning. Imagery fills every page, imagery of flight and heroes and sacrifice and love. There are beautiful poems to break through the drudgery and pain of everyday living. And so many amazing characters. There is Raami herself, of course, introspective and lonely for most of the book as she sees society fall apart around her. And her mother, one of the strongest and most resourceful women I've read about in some time, who works tirelessly for her daughter. And Raami's father, the poet prince, who stands for everything that is lost in the revolution - culture and beauty and happy times. And so many others who exemplify generosity and kindness of spirit, or hopelessness and despair.

Obviously, any book about civil war and revolution and genocide is not easy to read. And this book is about all those things. But it's also about the bonds that can grow and strengthen between people, about the different kinds of sacrifice that parents and lovers choose to make for the people who matter most to them, and about all of the ways that humans have of surviving hardship and making the most of what they have, all of the stories we tell ourselves about the heroes that came before and the beauty that they saw in our flawed, imperfect world. Absolutely beautiful - I hope you give it a try.

In the Shadow of the Banyan, by Vaddey Ratner, is set during the Cambodian civil war of the 1970s. We first meet our narrator, Raami, living a charmed life as a royal princess on an idyllic estate in Phnon Penh. But very quickly, revolution comes and Raami's family must leave their home to go become workers in the country. This is especially difficult for Raami as she suffered from polio as a baby and has difficulty walking. It's also difficult for her royal father, who believes in the ideals of the revolution but must hide his identity for his family's safety. He makes a sacrifice that most can't understand and that his family finds it difficult to forget. As Raami is shuffled from one place to another, connecting with some people and completely dissociating herself from others, working long, hard hours and slowly starving, we see the Cambodian civil war in all its terrible reality, and learn the power that stories can have to lift us away from our lives.

I cannot believe that this is Ratner's first novel, and in her second language, no less. The writing was absolutely stunning. Imagery fills every page, imagery of flight and heroes and sacrifice and love. There are beautiful poems to break through the drudgery and pain of everyday living. And so many amazing characters. There is Raami herself, of course, introspective and lonely for most of the book as she sees society fall apart around her. And her mother, one of the strongest and most resourceful women I've read about in some time, who works tirelessly for her daughter. And Raami's father, the poet prince, who stands for everything that is lost in the revolution - culture and beauty and happy times. And so many others who exemplify generosity and kindness of spirit, or hopelessness and despair.

Obviously, any book about civil war and revolution and genocide is not easy to read. And this book is about all those things. But it's also about the bonds that can grow and strengthen between people, about the different kinds of sacrifice that parents and lovers choose to make for the people who matter most to them, and about all of the ways that humans have of surviving hardship and making the most of what they have, all of the stories we tell ourselves about the heroes that came before and the beauty that they saw in our flawed, imperfect world. Absolutely beautiful - I hope you give it a try.

Monday, July 22, 2013

A 13th century travel guide to wondrous places

I purchased the book Invisible Cities, by Italo Calvino, after hearing one of the author's short stories on an episode of Radiolab. I was completely mesmerized by the story and wanted immediately to read more by the author. I chose Invisible Cities because the premise just seemed so fascinating. It's based on imagined conversations between famed explorer Marco Polo and the emperor Kublai Khan. Each section begins and ends with bits of conversation between the two men and each short chapter is Marco Polo's description of a different, fantastical city that he has visited within Kublai Khan's realm.

I should say right from the start that there is no plot in this book. This was a surprise to me and I was on uneven footing through the first few chapters, unsure of whether I was reading the book correctly or if I had missed something major, or what happened. It also isn't a book with great characters. While Marco Polo and Kublai Khan to us are larger than life and would be expected to dominate the narrative, they do not. You learn about them in subtle ways, through their conversations and their descriptions of cities, but you do not know them any better than they want you to know them and they are not the stars of this collection.

This short book, more than anything else, is about the power that words have to evoke a setting, utterly and completely. The cities that Marco Polo describes do not exist, but gosh, you wish they did. This is where Calvino's genius for description, for using just the right word to get across exactly what he wants the reader to take away, really comes through. I wish I could read Italian because I can't help feeling that something must have been lost in translation. This is not because I read a bad translation - I didn't, the language was beautiful - but because I feel like each word was chosen with such care that I would like to read the book in Calvino's chosen language. In a way, I felt like each chapter was a poem. They were all so short - between two and three pages long - and they evoked such a sense of nostalgia for places that do not even exist, and with such a succinct use of words - that they felt very poem-like to me.

I read this book while traveling, which I think was ideal. As you walk around unfamiliar places, I think you notice things that the locals ignore or don't think about any more, and you are very aware of how the city feels and what its personality is. Calvino takes that feeling to an extreme by making his cities as magical as possible so that you have a sense not just of the physical attributes of the city, but the more nebulous aspects, too - the atmosphere and vibe that are so hard to describe to other people.

And each chapter is such a delight. I don't want to ruin the experience of reading something so different for you, but I do want you to get a sense of what is waiting for you. There's one city that exists on a spiderweb. One that is built in men's dreams of chasing a woman. One that has only the plumbing but none of the buildings. One that is built entirely on massive stilts. So many inventive and creative places to visit!

I admit this book wasn't what I was expecting. I really wanted to read a novel by Calvino and this is certainly not a novel. I was disappointed at the lack of characters and plot and context. But I can still get a novel by Calvino and enjoy that. This was a different, completely new, kind of treat, and I think if you go into the book knowing that it really is just a series of vignettes that describe cities you wish truly were in our world, then you would really enjoy it. The language is beautiful, and the cities - I wish there were accompanying illustrations for each chapter!

I should say right from the start that there is no plot in this book. This was a surprise to me and I was on uneven footing through the first few chapters, unsure of whether I was reading the book correctly or if I had missed something major, or what happened. It also isn't a book with great characters. While Marco Polo and Kublai Khan to us are larger than life and would be expected to dominate the narrative, they do not. You learn about them in subtle ways, through their conversations and their descriptions of cities, but you do not know them any better than they want you to know them and they are not the stars of this collection.

This short book, more than anything else, is about the power that words have to evoke a setting, utterly and completely. The cities that Marco Polo describes do not exist, but gosh, you wish they did. This is where Calvino's genius for description, for using just the right word to get across exactly what he wants the reader to take away, really comes through. I wish I could read Italian because I can't help feeling that something must have been lost in translation. This is not because I read a bad translation - I didn't, the language was beautiful - but because I feel like each word was chosen with such care that I would like to read the book in Calvino's chosen language. In a way, I felt like each chapter was a poem. They were all so short - between two and three pages long - and they evoked such a sense of nostalgia for places that do not even exist, and with such a succinct use of words - that they felt very poem-like to me.

I read this book while traveling, which I think was ideal. As you walk around unfamiliar places, I think you notice things that the locals ignore or don't think about any more, and you are very aware of how the city feels and what its personality is. Calvino takes that feeling to an extreme by making his cities as magical as possible so that you have a sense not just of the physical attributes of the city, but the more nebulous aspects, too - the atmosphere and vibe that are so hard to describe to other people.

And each chapter is such a delight. I don't want to ruin the experience of reading something so different for you, but I do want you to get a sense of what is waiting for you. There's one city that exists on a spiderweb. One that is built in men's dreams of chasing a woman. One that has only the plumbing but none of the buildings. One that is built entirely on massive stilts. So many inventive and creative places to visit!