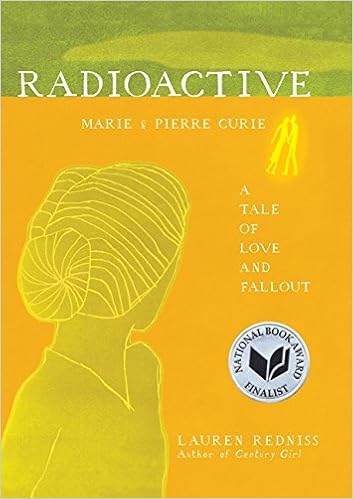

Lauren Redniss' Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie - A Tale of Love and Fallout is a beautiful book. It is beautiful because of the amazingly subtle artwork that implies more than it compels, because of the process used to create that artwork, because of the typeface the author created herself based on manuscripts she saw at the New York Public Library, because of the archives and research Redniss delved into and included in the book to make it both very informative and intensely personal.

Redniss' book is different than many other graphic novels. It's not structured in panels, but in full page illustrations, sometimes accompanied by dense, descriptive text. It includes many types of artwork, from cyanotype printing (used to achieve a look similar to a radioactive glow), photos, grave rubbings, sketches, and more. There is a Chernobyl Situational Map and photos of mutant flowers. It's absolutely stunning.

Radioactive is described as the story of Marie & Pierre Curie, but that's more of a starting point than the arc of the whole story. Pierre & Marie Curie's partnership was hugely productive, but Marie lived a full life after her husband's untimely death (including earning herself a second Nobel Prize). She raised seriously amazing scientist children and inspired other scientists and changed the world.

She slept with a bottle of lightly glowing radium next to her bed. Her clothes and skin glowed. She had an affair with her husband's former student. She won two Nobel Prizes. During World War I, she made France mobile X-labs. She died a slow, painful death due to radiation exposure, working to the last as she described her "crisis and pus."

Redniss used Marie Curie's life as the centerpoint of her web, but she goes well beyond the lives of the Curies to describe just how much her work has inspired and influenced other people and how much it has impacted the world. Her work helped develop chemotherapy, treatment still used by cancer treatments today. Conversely, it led to significant work on the development of the atomic bomb. Many people in the world became ill or died due to their work with radium; others were inspired by it to study science.

I admit that sometimes this book could be hard for me to follow, and sometimes I had difficulty finding the thread between the Curie storyline and others. But I really, really enjoyed this book. The artwork is stunning, almost hypnotic. Curie's life is fascinating, her work ground-breaking. And it was so inspiring to read about all these truly amazing women.

Showing posts with label biography. Show all posts

Showing posts with label biography. Show all posts

Monday, July 17, 2017

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

Trevor Noah's Born a Crime

I don't watch The Daily Show very often, mostly because I don't watch TV all that often. I didn't know much at all about Trevor Noah when he took over after Jon Stewart left. I have only watched a few episodes since then, and Noah's style is very different. He's much less angry, more willing to seek common ground. That's not to say that Jon Stewart was too jaded for his job, but you could see it wear on him, every day talking about important topics but not seeming to make any real difference.

I became interested in reading Trevor Noah's memoir, Born a Crime, after listening to some interviews with him when the book came out. I liked many of the things he said, and the very genuine way in which he said them. He does want to connect with people and find the many ways in which we are alike and can share moments and experiences vs harping on details that can tear us apart. I appreciate this kindness and empathy in him, particularly as he is someone who works in comedy and late night and news media that depends on ratings.

Noah's book is about his childhood and early adulthood in South Africa. It's not exhaustive; there are clearly some episodes that are quite painful and he does not dwell on those. It is more episodic in nature; the only people we get to know well and who feature prominently through the entire book are Trevor and his mother. Noah's mother seems like an amazing woman. She is deeply religious, and Trevor grew up going to multiple churches multiple days a week. She is also fiercely independent. She chose to live on her own in a dangerous city and have a mixed race child out of wedlock while living under apartheid. She raised him to believe that he could do anything. She worked and worked and worked, and when she married someone, she married an abusive alcoholic and the police never once helped to keep her safe.

Honestly, having read this book, the only word I can possibly use to describe Trevor Noah and his mom is resilient. Noah grew up in a very, very difficult environment. His family was extremely poor, he often went hungry, he was a mixed race kid in a country that was obsessed with race, and there seemed to be very little stability in his life. And yet he seems never to have lost his kindness and gentleness. This book makes me want to watch The Daily Show because I want to support empathy. It makes me respect religion and deeply religious people more because when religion is done right, it really can make people strive to become better, kinder versions of themselves.

I don't think I finished this book knowing Trevor Noah any better than I did going into it. I understand his background and his life better, but I do think he holds the reader just a little bit away. I think he has a lot of painful memories, and I don't think he wants to revisit them or dwell on them too deeply. Instead, he writes about events that shaped his thinking and who he became. He talks about the help he received and how grateful he is for that help and acknowledges that a lot of people don't get help. He talks about his mother and the moment he realized that women are often much more vulnerable than men in a situation. He talks about the time he realized that the police aren't always great people, that they are human and come into situations with their own histories and biases. And through it all, he shows readers (as kindly and diplomatically as possible) why he believes what he believes.

A quote that exemplifies what I am trying to explain above about Noah's approach:

I became interested in reading Trevor Noah's memoir, Born a Crime, after listening to some interviews with him when the book came out. I liked many of the things he said, and the very genuine way in which he said them. He does want to connect with people and find the many ways in which we are alike and can share moments and experiences vs harping on details that can tear us apart. I appreciate this kindness and empathy in him, particularly as he is someone who works in comedy and late night and news media that depends on ratings.

Noah's book is about his childhood and early adulthood in South Africa. It's not exhaustive; there are clearly some episodes that are quite painful and he does not dwell on those. It is more episodic in nature; the only people we get to know well and who feature prominently through the entire book are Trevor and his mother. Noah's mother seems like an amazing woman. She is deeply religious, and Trevor grew up going to multiple churches multiple days a week. She is also fiercely independent. She chose to live on her own in a dangerous city and have a mixed race child out of wedlock while living under apartheid. She raised him to believe that he could do anything. She worked and worked and worked, and when she married someone, she married an abusive alcoholic and the police never once helped to keep her safe.

Honestly, having read this book, the only word I can possibly use to describe Trevor Noah and his mom is resilient. Noah grew up in a very, very difficult environment. His family was extremely poor, he often went hungry, he was a mixed race kid in a country that was obsessed with race, and there seemed to be very little stability in his life. And yet he seems never to have lost his kindness and gentleness. This book makes me want to watch The Daily Show because I want to support empathy. It makes me respect religion and deeply religious people more because when religion is done right, it really can make people strive to become better, kinder versions of themselves.

I don't think I finished this book knowing Trevor Noah any better than I did going into it. I understand his background and his life better, but I do think he holds the reader just a little bit away. I think he has a lot of painful memories, and I don't think he wants to revisit them or dwell on them too deeply. Instead, he writes about events that shaped his thinking and who he became. He talks about the help he received and how grateful he is for that help and acknowledges that a lot of people don't get help. He talks about his mother and the moment he realized that women are often much more vulnerable than men in a situation. He talks about the time he realized that the police aren't always great people, that they are human and come into situations with their own histories and biases. And through it all, he shows readers (as kindly and diplomatically as possible) why he believes what he believes.

A quote that exemplifies what I am trying to explain above about Noah's approach:

People love to say, "Give a man a fish, and he'll eat for a day. Teach a man to fish, and he'll eat for a lifetime." What they don't say is, "And it would be nice if you gave him a fishing rod." That's the part of the analogy that's missing. Working with Andrew was the first time in my life I realized you need someone from the privileged world to come to you and say, "Okay, here's what you need, and here's how it works." Talent alone would have gotten me nowhere without Andrew giving me the CD writer. People say, "Oh, that's a handout." No. I still have to work to profit by it. But I don't stand a chance without it.This was an excellent book, and I bought a copy for my keeper shelf. Highly recommended.

Labels:

#diversiverse,

africa,

biography,

contemporary,

family,

non-fiction,

race

Monday, January 9, 2017

The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson

I took advantage of having a big chunk of free time off work between Christmas and New Year's to tackle a big, meaty book. I saw Isabel Wilkerson speak during the Chicago Humanities Festival after the election in November, and I had a feeling that her book would be a great one for me to read to start the new year.

The Warmth of Other Suns is about the Great Migration, the movement of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North over several decades in the 20th century. Wilkerson conducted hundreds of interviews. Her book compiles many people's stories, though she focuses on three people who left various areas of the South at different times and went to New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles to start new lives.

This book is excellent. It is 540 pages of personal stories, which probably sounds like a lot, but it is not. It feels like you are in the same room as these people as they tell you about their lives, the decisions they made, the regrets they have, the people they knew. It's almost like a gigantic, written version of This American Life.

Like many people, I am struggling to come to grips with the way the world seems to be moving backwards to tribalism, distrust, and fear. Reading Wilkerson's book was empowering. When she came to speak at the Humanities Festival, she said something that I keep going back to. I am paraphrasing, but the gist of it was, "The lesson of the Great Migration is the power of an individual choice. They freed themselves."

Often, when reading books about minorities in the US, the general trend of stories is the same. People who are different show up. The people who are already there become angry. They treat the newcomers badly (sometimes, really really badly). The newcomers fight for their rights. Sometimes they win. It's an important story to tell because it happens so consistently, probably everywhere, but definitely in the United States. But it's also just depressing and disheartening. People are so frightened by anything that is different, no matter how superficial that difference might be, or no matter how ridiculous that fear is. And they fight back in terrifying, brutal ways.

But even against all that, a backdrop of hate and threats and physical violence, people fight. And that's what was so, so wonderful about this book. Even people with very little of their own, barely scraping by and with no rights of their own - they resisted and they fought and they made the world a more accepting and welcoming and equal place for all of us. As Wilkerson said, "The Great Migration... was a step in freeing not just the people who fled, but the country whose mountains they crossed... It was, if nothing else, an affirmation of the power of an individual decision, however powerless the individual might appear on the surface."

A few snapshots from this book really stood out to me:

1. Ida Mae Gladney coming to Chicago in the 1930s and realizing that she had the opportunity and the right to vote and that her vote would be heard and counted. She had never even bothered trying to vote before. Many, many years later, she would vote for Barack Obama for Illinois state senator.

2. Robert Foster's desperate search for a motel to spend the night on his drive to his new life in Los Angeles. He went from motel to motel and was denied a room at every single one. Finally, he broke down and told one couple that he was a veteran, that he was a physician, that he meant no harm to anyone and just wanted to sleep. They still refused.

3. The story of a man who worked with the NAACP, was locked up in a mental institution, and then escaped with the help of a coordinated effort that had him in a coffin and traveling across state lines in different hearses.

4. The store clerk who owned a dog and taught that dog many tricks. One trick was for the clerk to ask the dog if he'd rather be black or dead. The dog was trained to respond by rolling over and playing dead.

There were many more stories about oppression and resistance, the times people bowed to authority and the times they defied it. The many ways that people faced indignities and swallowed the insults, turned the other cheek, and then came back to fight another round. The consequences of leaving behind family and friends to start a new life. The consequences of working long, hard hours to make a better life for a family that you rarely get to see. The consequences of moving from the rural south to the industrial north.

I don't think I've done a good job of describing why this book is so moving. But it's a huge book, and it covers so much! It's hard to cover all of that in one post. All I can say is that it is an excellent story of how much progress we've made and the cost of that progress, not only for the country as a whole but for so many individual people. And it serves as an important reminder that individual decisions matter and can make a difference in the world.

The Warmth of Other Suns is about the Great Migration, the movement of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North over several decades in the 20th century. Wilkerson conducted hundreds of interviews. Her book compiles many people's stories, though she focuses on three people who left various areas of the South at different times and went to New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles to start new lives.

This book is excellent. It is 540 pages of personal stories, which probably sounds like a lot, but it is not. It feels like you are in the same room as these people as they tell you about their lives, the decisions they made, the regrets they have, the people they knew. It's almost like a gigantic, written version of This American Life.

Like many people, I am struggling to come to grips with the way the world seems to be moving backwards to tribalism, distrust, and fear. Reading Wilkerson's book was empowering. When she came to speak at the Humanities Festival, she said something that I keep going back to. I am paraphrasing, but the gist of it was, "The lesson of the Great Migration is the power of an individual choice. They freed themselves."

Often, when reading books about minorities in the US, the general trend of stories is the same. People who are different show up. The people who are already there become angry. They treat the newcomers badly (sometimes, really really badly). The newcomers fight for their rights. Sometimes they win. It's an important story to tell because it happens so consistently, probably everywhere, but definitely in the United States. But it's also just depressing and disheartening. People are so frightened by anything that is different, no matter how superficial that difference might be, or no matter how ridiculous that fear is. And they fight back in terrifying, brutal ways.

But even against all that, a backdrop of hate and threats and physical violence, people fight. And that's what was so, so wonderful about this book. Even people with very little of their own, barely scraping by and with no rights of their own - they resisted and they fought and they made the world a more accepting and welcoming and equal place for all of us. As Wilkerson said, "The Great Migration... was a step in freeing not just the people who fled, but the country whose mountains they crossed... It was, if nothing else, an affirmation of the power of an individual decision, however powerless the individual might appear on the surface."

A few snapshots from this book really stood out to me:

1. Ida Mae Gladney coming to Chicago in the 1930s and realizing that she had the opportunity and the right to vote and that her vote would be heard and counted. She had never even bothered trying to vote before. Many, many years later, she would vote for Barack Obama for Illinois state senator.

2. Robert Foster's desperate search for a motel to spend the night on his drive to his new life in Los Angeles. He went from motel to motel and was denied a room at every single one. Finally, he broke down and told one couple that he was a veteran, that he was a physician, that he meant no harm to anyone and just wanted to sleep. They still refused.

3. The story of a man who worked with the NAACP, was locked up in a mental institution, and then escaped with the help of a coordinated effort that had him in a coffin and traveling across state lines in different hearses.

4. The store clerk who owned a dog and taught that dog many tricks. One trick was for the clerk to ask the dog if he'd rather be black or dead. The dog was trained to respond by rolling over and playing dead.

There were many more stories about oppression and resistance, the times people bowed to authority and the times they defied it. The many ways that people faced indignities and swallowed the insults, turned the other cheek, and then came back to fight another round. The consequences of leaving behind family and friends to start a new life. The consequences of working long, hard hours to make a better life for a family that you rarely get to see. The consequences of moving from the rural south to the industrial north.

I don't think I've done a good job of describing why this book is so moving. But it's a huge book, and it covers so much! It's hard to cover all of that in one post. All I can say is that it is an excellent story of how much progress we've made and the cost of that progress, not only for the country as a whole but for so many individual people. And it serves as an important reminder that individual decisions matter and can make a difference in the world.

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Hope Jahren's Lab Girl

One of the things I most missed about blogging while I was in and out this year was discussing books with you guys. Thus, one of the first things I did when I came back to blogging was to plan a buddy read with one of my favoritest and longest-lasting blogging friends, Ana of things mean a lot. We chose to read Hope Jahren's memoir Lab Girl because reading about women rocking the science world seemed like a really nice thing to do after the horrors (that continue) of Brexit and the American Presidential election.

Lab Girl is written by a plant biologist who does research on topics that seem to be quite fascinating (at least at the macro level. At the micro level, it seems like a lot of sorting through dirt). She writes about how she got into biology, her life as a biologist, and her friendship with someone who is hugely important to her personal and professional life. Throughout the book, there are vignettes that describe the life of a tree, from seed to seedling to battling disease and other threats to communicating with other plants. Those vignettes are beautiful.

Unfortunately, Lab Girl wasn't quite what we were expecting, and neither of us loved it as much as we'd hoped. But there were some really great parts! Below is our discussion of the book, if you care to read it:

Lab Girl is written by a plant biologist who does research on topics that seem to be quite fascinating (at least at the macro level. At the micro level, it seems like a lot of sorting through dirt). She writes about how she got into biology, her life as a biologist, and her friendship with someone who is hugely important to her personal and professional life. Throughout the book, there are vignettes that describe the life of a tree, from seed to seedling to battling disease and other threats to communicating with other plants. Those vignettes are beautiful.

Unfortunately, Lab Girl wasn't quite what we were expecting, and neither of us loved it as much as we'd hoped. But there were some really great parts! Below is our discussion of the book, if you care to read it:

Labels:

biography,

contemporary,

non-fiction,

science,

women

Thursday, April 28, 2016

How to follow your dreams and disappoint your parents

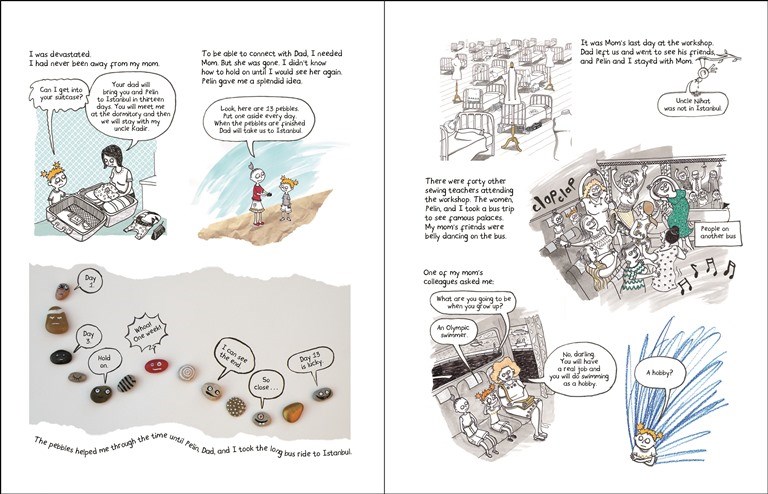

I am not sure why comics are such great vehicles for memoirs, particularly memoirs of growing up and coming of age. Whatever it is, I definitely have a weakness for memoirs in comic book form (whereas I hardly ever read memoirs in prose). So when I heard about Ozge Samanci's Dare to Disappoint, her memoir of growing up in Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s, I put it straight on my library wish list.

As usual, I have no idea where I first heard about this book. I think possibly on some comic book round-up from the end of 2015. While the story itself is nothing earth-shattering or ground-breaking, it's related in a very endearing and visually appealing way, and I really enjoyed it.

Ozge grew up in a pretty tense environment. Turkey was in a period of high militarization, religious fervor and conflict, and an opening of the economy and culture to outside influences. In the midst of all that, Ozge's parents worked very hard at low-paying jobs; they were insistent that Ozge and her older sister would do better for themselves. Only study engineering at the very top school! Otherwise, they'd be failures.

As someone who grew up in an Indian household, I completely understood the pressure Ozge felt to do well in subjects that were not nearly as interesting to her as others were (though, to be fair, Indian parents require their kids to be good in all subjects, not just math and science). Similarly, I can understand parents' deep desire to ensure that their children's lives are easier and more comfortable than their own.

As this is a pretty universal conflict, it's not really Ozge's struggles that draw you into the story, though they are shared in a humorous and entertaining manner. Instead, it's the juxtaposition of her coming-of-age against Turkey's growing pains. She learns about herself, understands her environment better, and navigates a complicated system. All with the help of fun, colorful illustrations and collages.

I really enjoyed learning more about Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s, at the end of the Cold War. It's always fun to learn about everyday life in a different place, particularly when systems are set up so differently from what you are used to. For example, Turkey's school system was set up (maybe still is?) in such a way that you had to do really well on tests to advance to the good schools and the well-paying jobs. Students practiced military drills at school. Ozge encounters devout Muslims (she is not one herself), studies and works herself to exhaustion, discovers boys, chats with Jacques Cousteau, and tries to figure out what she wants to do with her life.

Dare to Disappoint is not likely to change your world or blow your bind, but it's funny, bright, and thoughtful. If you're a fan of comics or of coming-of-age stories or memoirs (that's a pretty wide range), then I'd recommend checking it out.

As usual, I have no idea where I first heard about this book. I think possibly on some comic book round-up from the end of 2015. While the story itself is nothing earth-shattering or ground-breaking, it's related in a very endearing and visually appealing way, and I really enjoyed it.

Ozge grew up in a pretty tense environment. Turkey was in a period of high militarization, religious fervor and conflict, and an opening of the economy and culture to outside influences. In the midst of all that, Ozge's parents worked very hard at low-paying jobs; they were insistent that Ozge and her older sister would do better for themselves. Only study engineering at the very top school! Otherwise, they'd be failures.

As someone who grew up in an Indian household, I completely understood the pressure Ozge felt to do well in subjects that were not nearly as interesting to her as others were (though, to be fair, Indian parents require their kids to be good in all subjects, not just math and science). Similarly, I can understand parents' deep desire to ensure that their children's lives are easier and more comfortable than their own.

As this is a pretty universal conflict, it's not really Ozge's struggles that draw you into the story, though they are shared in a humorous and entertaining manner. Instead, it's the juxtaposition of her coming-of-age against Turkey's growing pains. She learns about herself, understands her environment better, and navigates a complicated system. All with the help of fun, colorful illustrations and collages.

I really enjoyed learning more about Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s, at the end of the Cold War. It's always fun to learn about everyday life in a different place, particularly when systems are set up so differently from what you are used to. For example, Turkey's school system was set up (maybe still is?) in such a way that you had to do really well on tests to advance to the good schools and the well-paying jobs. Students practiced military drills at school. Ozge encounters devout Muslims (she is not one herself), studies and works herself to exhaustion, discovers boys, chats with Jacques Cousteau, and tries to figure out what she wants to do with her life.

Dare to Disappoint is not likely to change your world or blow your bind, but it's funny, bright, and thoughtful. If you're a fan of comics or of coming-of-age stories or memoirs (that's a pretty wide range), then I'd recommend checking it out.

Labels:

asia,

biography,

contemporary,

europe,

graphic novel,

young adult

Monday, April 11, 2016

Delicious eats and food for thought

I really love the food documentaries on Netflix. I enjoyed The Chef's Table, I really liked For Grace, and I am sure I will eat up (haha, pun intended) whatever else Netflix recommends in my queue.

I don't actually do a lot of food-related reading, though. I am not sure why. Maybe I miss the visuals of the beautiful dishes or the sounds of pots clanging, meat sizzling, knives chopping.

I have never been to any of Marcus Samuelsson's restaurants before, though I have used his recipe for a garam masala pumpkin tart for Thanksgiving over the past few years. I really like Samuelsson's cooking in theory, though I have not experienced it in practice. Samuelsson was born in Ethiopia, grew up in Sweden, worked in restaurants around Europe and on the sea, and then moved to New York. His cooking style draws from all of his global experiences and tastes; hence, he has a recipe for garam masala pumpkin pie, melding the tastes of traditional American home-cooking with Indian spices. I love taking tastes that don't often go together and making them work, making something new and different. In a dorky and idealistic way, I feel like if people can see how their tastes are not so different and can complement each other to make stronger whole, then maybe it will help people see past their bigger and more philosophical differences, too.

Yes, Chef is Marcus Samuelsson's book about his life. In many ways, it's pretty typical of what you would expect from a chef. He didn't like school, he preferred being in the kitchen with his grandmother. He went to culinary school and worked harder and longer and better than anyone else. He was lucky enough to get a big break at a well-known restaurant, and from there he was off, with a few bumps and bruises along the way.

But in addition to that, Samuelsson shares some personal insights as well. For example, he grew up very dark-skinned in a very light-skinned environment. He faced overt and more subtle racism in the kitchen almost everywhere he went. A couple of times, he would be offered a job on paper but then show up for work and be told that there was no place for him. He talks a lot about how few minorities are in the kitchens of high-end restaurants, how few women, too. And how he is doing his part, working very hard to give people the opportunities that he often did not receive while he was training. Samuelsson never makes race or racism the dominant part of his narrative, but it clearly had a huge impact on his training and the way he learned to cook, and I think he addresses it really well. It's also clear just how much it has influenced every aspect of his cooking; he draws from so many different food cultures to create his recipes.

What's also obvious in this book is that being a chef is really hard and a ton of work. It takes a huge personal toll on people. Samuelsson missed both his grandmother's and his father's funerals because of work. He does not spend a lot of time being introspective about this, but it is hard to imagine. He also has a daughter, and for about the first 15 years of her life, he never made any attempt to contact her or get to know her. Obviously, Samuelsson had to deal with a lot of personal things and decisions as he grew and matured; while readers don't get a huge amount of insight into these very personal motivations and decisions, it's clear that he still struggles with them.

Samuelsson makes no secret that he enjoyed going out, having fun, meeting people and spending time with women. He also clearly has a ton of confidence in his skill and his decisions. He can sometimes sound arrogant, but I think it is just honesty. And it's hard not to love anyone who serves a meal at the White House and then comes home to Harlem and makes the exact same meal for his teenaged next-door neighbor and all her best friends. That was just lovely.

I enjoyed this book a lot, and now I really want to visit Samuelsson's restaurant in Harlem the next time I am in New York City! Here's a link to Red Rooster's website in case you want to see the fusion menu he has on there, too.

I don't actually do a lot of food-related reading, though. I am not sure why. Maybe I miss the visuals of the beautiful dishes or the sounds of pots clanging, meat sizzling, knives chopping.

I have never been to any of Marcus Samuelsson's restaurants before, though I have used his recipe for a garam masala pumpkin tart for Thanksgiving over the past few years. I really like Samuelsson's cooking in theory, though I have not experienced it in practice. Samuelsson was born in Ethiopia, grew up in Sweden, worked in restaurants around Europe and on the sea, and then moved to New York. His cooking style draws from all of his global experiences and tastes; hence, he has a recipe for garam masala pumpkin pie, melding the tastes of traditional American home-cooking with Indian spices. I love taking tastes that don't often go together and making them work, making something new and different. In a dorky and idealistic way, I feel like if people can see how their tastes are not so different and can complement each other to make stronger whole, then maybe it will help people see past their bigger and more philosophical differences, too.

Yes, Chef is Marcus Samuelsson's book about his life. In many ways, it's pretty typical of what you would expect from a chef. He didn't like school, he preferred being in the kitchen with his grandmother. He went to culinary school and worked harder and longer and better than anyone else. He was lucky enough to get a big break at a well-known restaurant, and from there he was off, with a few bumps and bruises along the way.

But in addition to that, Samuelsson shares some personal insights as well. For example, he grew up very dark-skinned in a very light-skinned environment. He faced overt and more subtle racism in the kitchen almost everywhere he went. A couple of times, he would be offered a job on paper but then show up for work and be told that there was no place for him. He talks a lot about how few minorities are in the kitchens of high-end restaurants, how few women, too. And how he is doing his part, working very hard to give people the opportunities that he often did not receive while he was training. Samuelsson never makes race or racism the dominant part of his narrative, but it clearly had a huge impact on his training and the way he learned to cook, and I think he addresses it really well. It's also clear just how much it has influenced every aspect of his cooking; he draws from so many different food cultures to create his recipes.

What's also obvious in this book is that being a chef is really hard and a ton of work. It takes a huge personal toll on people. Samuelsson missed both his grandmother's and his father's funerals because of work. He does not spend a lot of time being introspective about this, but it is hard to imagine. He also has a daughter, and for about the first 15 years of her life, he never made any attempt to contact her or get to know her. Obviously, Samuelsson had to deal with a lot of personal things and decisions as he grew and matured; while readers don't get a huge amount of insight into these very personal motivations and decisions, it's clear that he still struggles with them.

Samuelsson makes no secret that he enjoyed going out, having fun, meeting people and spending time with women. He also clearly has a ton of confidence in his skill and his decisions. He can sometimes sound arrogant, but I think it is just honesty. And it's hard not to love anyone who serves a meal at the White House and then comes home to Harlem and makes the exact same meal for his teenaged next-door neighbor and all her best friends. That was just lovely.

I enjoyed this book a lot, and now I really want to visit Samuelsson's restaurant in Harlem the next time I am in New York City! Here's a link to Red Rooster's website in case you want to see the fusion menu he has on there, too.

Labels:

#diversiverse,

audiobook,

biography,

contemporary,

food,

non-fiction,

race

Monday, January 4, 2016

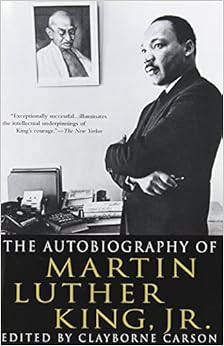

Martin Luther King, Jr., in his own words

I don't need to say this, but we've had a tumultuous several years in this world, haven't we? So many steps forward and so many steps backward, and it's hard to appreciate all the good in the midst of so much that is bad.

Police brutality has been in the news all over the United States and recently, my beloved Chicago has (deservedly) gained national attention due to the practices of its police department. There is not a federal investigation into the police department and there have been many protests in the streets, people demanding the mayor to step down.

Perhaps I have become very cynical lately, but I don't really see the point of protesting without very concrete demands; if you want the mayor to step down, then you should have someone ready to step up to the plate, take on the role. Otherwise, it feels incomplete and less compelling. This is happening all over America and probably the world. A lot of people are protesting and are 100% justified in protesting. But it's hard to understand what the next step will be.

All of this really made me want to learn more about leaders for positive change. And, given the environment and the country I live in, Martin Luther King, Jr. seemed the obvious choice. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. is not technically an autobiography in that MLK did not sit down to write his life story. But the book is comprised of his notes and letters and speeches and truly succeeds in bringing him to life. I highly recommend the audiobook version, which includes audio clips of MLK himself, so that you can truly understand what a charismatic and passionate speaker he was.

It is impossible to read this book and not think about the current climate in America. So many things that MLK brought up and fought for are still issues today. Clearly, police brutality still exists. Schools are still highly segregated, even if they are not meant to be. There are still slums, still low-paying jobs, still a disproportionate economic impact of recession. In the book, Martin Luther King is quoted as saying that he never faced such racism and hatred anywhere in America as he faced in Chicago, and while I hope that's changed, I don't know that Chicago has done much to earn accolades. The city is still segregated, many people refuse to even drive through certain neighborhoods, and there are more victims of gun and gang violence here than probably anywhere else in the country. Most of those victims are black.

Living through the most recent political and social movements in the world, from Occupy Wall Street to Arab Spring to all the other protest movements that ebb and flow, the success of Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement are even more striking. It is very difficult to make the status quo into an issue that people will care about, that they will fight for, that leaders will take notice of. I am truly amazed at what they were able to do. It is inspiring to read about and listen to and think about where we are now vs where we were then, and where we want to be in another fifty years to continue to progress and become the people, the society, the world that we want to be.

This is an excellent read for anyone who wants to learn more about Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement. And for anyone who needs to believe that a small group of people can make great big changes in the world. Highly recommended.

Police brutality has been in the news all over the United States and recently, my beloved Chicago has (deservedly) gained national attention due to the practices of its police department. There is not a federal investigation into the police department and there have been many protests in the streets, people demanding the mayor to step down.

Perhaps I have become very cynical lately, but I don't really see the point of protesting without very concrete demands; if you want the mayor to step down, then you should have someone ready to step up to the plate, take on the role. Otherwise, it feels incomplete and less compelling. This is happening all over America and probably the world. A lot of people are protesting and are 100% justified in protesting. But it's hard to understand what the next step will be.

All of this really made me want to learn more about leaders for positive change. And, given the environment and the country I live in, Martin Luther King, Jr. seemed the obvious choice. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. is not technically an autobiography in that MLK did not sit down to write his life story. But the book is comprised of his notes and letters and speeches and truly succeeds in bringing him to life. I highly recommend the audiobook version, which includes audio clips of MLK himself, so that you can truly understand what a charismatic and passionate speaker he was.

It is impossible to read this book and not think about the current climate in America. So many things that MLK brought up and fought for are still issues today. Clearly, police brutality still exists. Schools are still highly segregated, even if they are not meant to be. There are still slums, still low-paying jobs, still a disproportionate economic impact of recession. In the book, Martin Luther King is quoted as saying that he never faced such racism and hatred anywhere in America as he faced in Chicago, and while I hope that's changed, I don't know that Chicago has done much to earn accolades. The city is still segregated, many people refuse to even drive through certain neighborhoods, and there are more victims of gun and gang violence here than probably anywhere else in the country. Most of those victims are black.

Living through the most recent political and social movements in the world, from Occupy Wall Street to Arab Spring to all the other protest movements that ebb and flow, the success of Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement are even more striking. It is very difficult to make the status quo into an issue that people will care about, that they will fight for, that leaders will take notice of. I am truly amazed at what they were able to do. It is inspiring to read about and listen to and think about where we are now vs where we were then, and where we want to be in another fifty years to continue to progress and become the people, the society, the world that we want to be.

This is an excellent read for anyone who wants to learn more about Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement. And for anyone who needs to believe that a small group of people can make great big changes in the world. Highly recommended.

Monday, September 28, 2015

#GOAT

I grew up in Chicago in the 90s, and my entire family (and really, the entire city) was completely obsessed with the Chicago Bulls basketball team. Scottie Pippen is my all-time favorite player, and I'm still a huge fan of the team (though they have the tendency to break my heart more these days than they ever did in the 90s).

The most dominant player of the 90s era (and possibly of all time) was Michael Jordan. Pretty much as soon as I saw that there was a new-ish biography out about Jordan, I planned to read it. Looking back at Jordan's time with the Bulls, it is amazing that the team did so well so consistently for so long. I really wanted to look back on that amazing period.

Michael Jordan: The Life, by Roland Lazenby, is an account of Jordan's life, including his family, close friends, and his very volatile relationships with the teams he played on. Quite honestly, I don't know if this book would appeal to anyone who is not a big sports fan in general or a huge Bulls fan in particular. I debated whether I should even write a review because it's hard to be objective about a book when it's about a childhood hero. I'm certainly not an objective reader here.

Lazenby's book is very detailed. There's a lot of time spent on Jordan's family history and his childhood, which I really appreciated. There's also beautiful writing about the games Jordan played, the way he moved on the court, the way he could dominate everyone. I wish that the book had been a more multimedia experience; so many times, I wanted to go to YouTube and find the play that Lazenby was describing.

What comes across on almost every page is just how competitive Michael Jordan is. He was able to pump himself up for every game, wanted to win every single game. When you consider that the regular season of the NBA stretches from November to April and includes 82 games, that is absolutely mind-blowing. He competed not only with other teams, but also with his teammates, forcing them to get better, and with himself, always drilling, always pushing to see how much further he could go and how much better he could become. He rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. But the fans hardly ever saw that; they saw an amazing player, a team leader, a media darling. And, of course, they saw all of his commercials. Nike, Gatorade, McDonald's... but mostly Nike. I was fascinated by the Nike deal and all the implications that contract had for Jordan and for Nike.

But fame and fortune have their drawbacks. And someone so obsessed with competition and winning can easily become addicted to something like gambling. Michael Jordan gambled a lot. And for huge sums of money. He also had a large family and group of friends that depended on him for all sorts of things, and the massive sums of money he made created a lot of tension with them, too.

As a fan, you really only see your team on the court. To you, they don't really have anything else going on. No personal lives, no triumphs or failures, no issues with teammates or family or friends. All you care about is how they play. In that way, I really appreciated Lazenby's book. I enjoyed getting a peek behind the Bulls organization of my childhood and understanding just how special that team was.

The most dominant player of the 90s era (and possibly of all time) was Michael Jordan. Pretty much as soon as I saw that there was a new-ish biography out about Jordan, I planned to read it. Looking back at Jordan's time with the Bulls, it is amazing that the team did so well so consistently for so long. I really wanted to look back on that amazing period.

Michael Jordan: The Life, by Roland Lazenby, is an account of Jordan's life, including his family, close friends, and his very volatile relationships with the teams he played on. Quite honestly, I don't know if this book would appeal to anyone who is not a big sports fan in general or a huge Bulls fan in particular. I debated whether I should even write a review because it's hard to be objective about a book when it's about a childhood hero. I'm certainly not an objective reader here.

Lazenby's book is very detailed. There's a lot of time spent on Jordan's family history and his childhood, which I really appreciated. There's also beautiful writing about the games Jordan played, the way he moved on the court, the way he could dominate everyone. I wish that the book had been a more multimedia experience; so many times, I wanted to go to YouTube and find the play that Lazenby was describing.

What comes across on almost every page is just how competitive Michael Jordan is. He was able to pump himself up for every game, wanted to win every single game. When you consider that the regular season of the NBA stretches from November to April and includes 82 games, that is absolutely mind-blowing. He competed not only with other teams, but also with his teammates, forcing them to get better, and with himself, always drilling, always pushing to see how much further he could go and how much better he could become. He rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. But the fans hardly ever saw that; they saw an amazing player, a team leader, a media darling. And, of course, they saw all of his commercials. Nike, Gatorade, McDonald's... but mostly Nike. I was fascinated by the Nike deal and all the implications that contract had for Jordan and for Nike.

But fame and fortune have their drawbacks. And someone so obsessed with competition and winning can easily become addicted to something like gambling. Michael Jordan gambled a lot. And for huge sums of money. He also had a large family and group of friends that depended on him for all sorts of things, and the massive sums of money he made created a lot of tension with them, too.

As a fan, you really only see your team on the court. To you, they don't really have anything else going on. No personal lives, no triumphs or failures, no issues with teammates or family or friends. All you care about is how they play. In that way, I really appreciated Lazenby's book. I enjoyed getting a peek behind the Bulls organization of my childhood and understanding just how special that team was.

Labels:

20th century,

america,

audiobook,

biography,

sports

Monday, September 21, 2015

Growing up Black in America

In accepting both the chaos of history and the fact of my total end, I was freed to truly consider how I wished to live - specifically, how do I live free in this black body? It is a profound question because America understands itself as God's handiwork, but the black body is the clearest evidence that America is the work of men.Ta-Nehisi Coates' letter to his son, published as the book Between the World and Me has justifiably garnered a lot of attention since its publication. As Americans struggle to understand their racial legacy, Coates' book provides us with a glimpse of what it was like for him to grow up Black.

For that reason alone, I think as many Americans as possible should read this book. I am lucky enough to have a diverse group of friends with whom I can frankly and honestly discuss race and gender issues. I realize that many people do not have that luxury, which is yet another reason why reading diversely is so important. Between the World and Me offers those people with an idea of just how terrifying it can be to be Black here. And it serves as a reminder to everyone that fear runs both ways. As frightened as a middle-class white man can be to see a black guy walking the streets of his neighborhood, it's pretty much guaranteed that the black guy feels just as frightened, except add in the fact that he probably doesn't trust the police to protect him, either.

There are so many parts of this book that made me so very sad. Coates is such an emotionally charged author. He pushes you and challenges you, and it was such a good lesson. Soon after finishing this book, I took a trip to Charleston, SC, and I think because the stories were so fresh in my mind, I found myself constantly telling myself and my friend, "Do not forget that these beautiful houses were built by slave labor. Do not forget, do not forget, do not forget." Of course, it's easier to remind yourself when you are a Northerner visiting the South, as Northerners love to think we have some sort of moral superiority to the South. We like to forget so much of our own horrifying history. Or the fact that when half the country uses slave labor, the entire country benefits from slave labor. I hope that all my reading about the black experience in America will help me to flush out my own biases, and constantly remind myself that my experience of America is not universal.

Other quotes that really stood out to me and the reasons why:

I have no desire to make you "tough" or "street," perhaps because any "toughness" I garnered came reluctantly. I think I was always, somehow, aware of the price. I think I somehow knew that that third of my brain should have been concerned with more beautiful things. I think I felt that something out there, some force, nameless and vast, had robbed me of ... what? Time? experience? I think you know something of what that third could have done, and I think that is why you may feel the need for escape even more than I did. You have seen all the wonderful life up above the tree-line, yet you understand that there is no real distance between you and Trayvon Martin, and thus Trayvon Martin must terrify you in a way that he could never terrify me. You have seen so much more of all that is lost when they destroy your body.That one had me in tears, really. The possibility of a life well-lived, lifelong friends, the potential and opportunity to do something extraordinary, so much of that passes through Chicago schools every day, and so much of it is lost to horrible schools, violence, and issues at home. Think of all the amazing, brilliant, artistic, world-changing people that our country has lost.

You may have heard the talk of diversity, sensitivity training, and body cameras. These are all fine and applicable, but they understate the task and allow the citizens of this country to pretend that there is real distance between their own attitudes and those of the ones appointed to protect them. The truth is that the police reflect America in all of its will and fear, and whatever we might make of this country's criminal justice policy, it cannot be said that it was imposed by a repressive minority.Many times in this book, Coates reiterates the point that no matter how successful, how polite, how friendly, how un-confrontational a black man can be in every moment of his life, it can all fall apart so quickly and so easily because someone else can just see you and feel frightened and take action. Many people move out of unsafe neighborhoods as quickly as they can, put their kids into excellent schools as early as they can, give them experiences and gifts that expand their minds in hopes of helping them become good, successful, happy people. But black men have to work so much harder for that to happen, and the possibility that it can all be taken away is ever-present.

"And one racist act. It's all it takes."

Thursday, February 26, 2015

"the best natured and best bred woman in England"

I have been making a concerted effort to read more of the books on my own shelves. Many of those books are non-fiction books about 18th and 19th century Britain, which has been my favorite era in history since reading Jane Austen for the first time. But in recent years, I've moved away from British history, and many of those books have sat unread while my reading tastes have changed.

But I picked up Amanda Foreman's Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and I realized that my tastes haven't changed so much. While I am so happy to be reading more widely and diversely than before, I do still love the Georgian era. And very few people personify the era as well as the Duchess of Devonshire.

A fashion icon, a published author, a serious party-goer with a gambling addiction, a political powerhouse much more impressive than her husband, an amateur geologist, and a loving mother, Georgiana Cavendish holds, in one person, all the excess and glory we associate with the late 1700s. I am not entirely sure how to provide a plot summary for a biography. Suffice it to say that Foreman gives us insights into every stage of Georgiana's life, from her childhood as her mother's favorite child, to her failed marriage with the Duke of Devonshire, to her desperation to have a son, and her serious, ever-present concerns about her gambling debts.

Foreman also brings the entire era to life (at least, the era as it was lived by the ridiculously rich people at the very top). She talks about 18th century politics at length and with authority, covers the French Revolution, and gives us a glimpse into the fashionable life. I admit the descriptions of men's fashion in particular completely bowled me over:

Georgiana was a leader of fashion herself, with the most epic hairstyles you can imagine. She is probably best remembered for her high-flying lifestyle and the scandalous three's company type existence she lived with her husband and her best friend, Lady Elizabeth Foster. Bess also happened to be her husband's mistress for several years and bore two of his children. But this is unfair to Georgiana. Foreman admits in her introduction that she fell more in love with Georgiana the more she read about her, and it's hard to read this book without falling in love with her yourself. Her life was so bittersweet:

Seriously, the Duchess was no joke. We get to know her pretty well, but there are still so many more things I wanted to know. So many things hinted at but frustratingly hard to find out. This may be because so many of her papers were lost or censored by later (ahem, Victorian) generations. It could also be because Foreman didn't have the inclination to write a much longer book. But there are so many events or people hinted at that fall to the wayside later on - for example, what was so unlikable about the Duke's daughter Caroline that everyone commented upon how awkward and weird she was as a child? And then she just disappears! And why in the world did Georgiana's daughter Harryo want to marry her aunt's lover? And what was Lady Elizabeth Foster really after? How did Georgiana treat her servants? How does one even begin to prepare for a dinner party with 1000 guests? I want to know!

But what I do know, even with those minor frustrations, is that history has given Georgiana the short shrift. She was so much more than she is given credit for, and when you read her letters and see how desperately lonely she was, and how she overcame that loneliness so much to be politically savvy and wonderfully kind and so generous, you will be as enchanted with her as London society was.

But if it was difficult to read this book and not fall in love with the duchess it was well nigh impossible to read it and not be completely astounded by the amount of money the aristocracy spent, burned, gambled, frittered away or just lost track of. Many of these people had 7- and 8-digit incomes or personal wealth and practically all of them were in debt. To each other. For gambling losses. I cannot even comprehend how one can be a millionaire one day and then lose an entire fortune that night to a passing acquaintance. I just... wow. Even though I feel pretty familiar with the Georgian era, I think I must severely underestimate just how strong the sense of entitlement was among the super-rich.

I thoroughly enjoyed this biography and highly recommend it. As Foreman points out, Georgiana was in every sense of the word a product of her time. She brilliantly maneuvered not just in the "women's sphere" of hearth and home but also used her influence and friends to make real and lasting impact on the larger world that we historically associate with men. She breaks down the entire notion of "separate spheres" and shows just how valuable women could be in the political arena. She's pretty amazing, and I'm glad to know more about her.

Note: The Georgians were really, really dramatic in pretty much everything they did. They wrote very effusive letters, they made grandiose gestures, said very intense things... it was truly awe-inspiring to read. I think the Victorians were pretty dramatic, too, so WHEN DID WE BECOME SO CALM? (Written in all capitals for ironic effect.) I was truly uncomfortable with the hair-tearing, the excessive weeping, the cloyingly affectionate (to me) descriptions - when did this happen? No wonder no one faints any more. We are all in a state of perpetual calm.

But I picked up Amanda Foreman's Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and I realized that my tastes haven't changed so much. While I am so happy to be reading more widely and diversely than before, I do still love the Georgian era. And very few people personify the era as well as the Duchess of Devonshire.

A fashion icon, a published author, a serious party-goer with a gambling addiction, a political powerhouse much more impressive than her husband, an amateur geologist, and a loving mother, Georgiana Cavendish holds, in one person, all the excess and glory we associate with the late 1700s. I am not entirely sure how to provide a plot summary for a biography. Suffice it to say that Foreman gives us insights into every stage of Georgiana's life, from her childhood as her mother's favorite child, to her failed marriage with the Duke of Devonshire, to her desperation to have a son, and her serious, ever-present concerns about her gambling debts.

Foreman also brings the entire era to life (at least, the era as it was lived by the ridiculously rich people at the very top). She talks about 18th century politics at length and with authority, covers the French Revolution, and gives us a glimpse into the fashionable life. I admit the descriptions of men's fashion in particular completely bowled me over:

Fox's particular contribution was to experiment with hair color, powdering his hair blue one day, red the next. He wore multicolored shoes and velvet frills...I mean, can you imagine this man with red hair and velvet frills? The mind boggles as to why all painters neglected to include this key identifying characteristic in any of his portraits.

|

| Charles James Fox, alas without red or blue powdered hair |

Georgiana was a leader of fashion herself, with the most epic hairstyles you can imagine. She is probably best remembered for her high-flying lifestyle and the scandalous three's company type existence she lived with her husband and her best friend, Lady Elizabeth Foster. Bess also happened to be her husband's mistress for several years and bore two of his children. But this is unfair to Georgiana. Foreman admits in her introduction that she fell more in love with Georgiana the more she read about her, and it's hard to read this book without falling in love with her yourself. Her life was so bittersweet:

She was an acknowledged beauty yet unappreciated by her husband, a popular leader of the ton who saw through its hypocrisy, and a woman whom people loved who was yet so insecure in her ability to command love that she became dependent on the suspect devotion of Lady Elizabeth Foster. She was a generous contributor to charitable causes who nevertheless stole from her friends, a writer who never published under her own name, a devoted mother who sacrificed one child to save the other three, a celebrity and patron of the arts in an era when married women had no legal status, a politician without a vote, and a skilled tactician a generation before the development of professional party politics.

Seriously, the Duchess was no joke. We get to know her pretty well, but there are still so many more things I wanted to know. So many things hinted at but frustratingly hard to find out. This may be because so many of her papers were lost or censored by later (ahem, Victorian) generations. It could also be because Foreman didn't have the inclination to write a much longer book. But there are so many events or people hinted at that fall to the wayside later on - for example, what was so unlikable about the Duke's daughter Caroline that everyone commented upon how awkward and weird she was as a child? And then she just disappears! And why in the world did Georgiana's daughter Harryo want to marry her aunt's lover? And what was Lady Elizabeth Foster really after? How did Georgiana treat her servants? How does one even begin to prepare for a dinner party with 1000 guests? I want to know!

But what I do know, even with those minor frustrations, is that history has given Georgiana the short shrift. She was so much more than she is given credit for, and when you read her letters and see how desperately lonely she was, and how she overcame that loneliness so much to be politically savvy and wonderfully kind and so generous, you will be as enchanted with her as London society was.

But if it was difficult to read this book and not fall in love with the duchess it was well nigh impossible to read it and not be completely astounded by the amount of money the aristocracy spent, burned, gambled, frittered away or just lost track of. Many of these people had 7- and 8-digit incomes or personal wealth and practically all of them were in debt. To each other. For gambling losses. I cannot even comprehend how one can be a millionaire one day and then lose an entire fortune that night to a passing acquaintance. I just... wow. Even though I feel pretty familiar with the Georgian era, I think I must severely underestimate just how strong the sense of entitlement was among the super-rich.

I thoroughly enjoyed this biography and highly recommend it. As Foreman points out, Georgiana was in every sense of the word a product of her time. She brilliantly maneuvered not just in the "women's sphere" of hearth and home but also used her influence and friends to make real and lasting impact on the larger world that we historically associate with men. She breaks down the entire notion of "separate spheres" and shows just how valuable women could be in the political arena. She's pretty amazing, and I'm glad to know more about her.

Note: The Georgians were really, really dramatic in pretty much everything they did. They wrote very effusive letters, they made grandiose gestures, said very intense things... it was truly awe-inspiring to read. I think the Victorians were pretty dramatic, too, so WHEN DID WE BECOME SO CALM? (Written in all capitals for ironic effect.) I was truly uncomfortable with the hair-tearing, the excessive weeping, the cloyingly affectionate (to me) descriptions - when did this happen? No wonder no one faints any more. We are all in a state of perpetual calm.

Monday, January 12, 2015

Life under the veil in Iran

I cannot believe it took me so long to read Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis. I saw the animated film years ago, but what really pushed me to read this one was when I saw Satrapi about a month ago at the Chicago Humanities Festival. She was just so vibrant and fun and apolitical (and said a lot of things about feminism that I pretty strongly disagree with) that it really made me want to read more of her books.

So, finally! Persepolis. The comic is the story of Satrapi's life in Iran, growing up with a big, liberal, loving family as the government becomes increasingly totalitarian. Satrapi writes about the early influences in her life - her grandfather and uncle, both of whom fought for people's rights. She moves onto her teenage years in Vienna, struggling to come of age in a country so foreign to her upbringing and so far from her family. And then the difficulties of coming home to an Iran that was so different than what she remembered, and became increasingly difficult to deal with.

I loved this book. The artwork and the writing are seamlessly integrated, in such a manner that I highly recommend Persepolis as a starter comic if you are concerned about reading a comic and are not sure how to deal with the words and pictures. I am always concerned that I don't pay enough attention to the artwork in graphic novels, but in Persepolis, I had none of that concern:

I also feel like Satrapi does such a great job of showing us everyday Iranian life. She did the same thing in Embroideries, and I can see why people say that Persepolis is so much better than Embroideries. What I enjoyed about Embroideries was the rich, deep relationships that existed between the women in the book. And that is true x1000 in Persepolis. There is such a deep love between Satrapi and her parents, between Satrapi and her grandmother. And her whole family is so supportive of her - not just when she shows her brilliance, but also when she makes mistakes. And they never tell her to be afraid or to bow down to authority - they let her make her own decisions and live her own life and are very proud of her when she stands up for her rights.

This was truly a beautifully written, funny, and wonderful book. I am so glad that I finally read it, and I can't wait to read Satrapi's Chicken with Plums and perhaps watch the movie that she directed this year!

So, finally! Persepolis. The comic is the story of Satrapi's life in Iran, growing up with a big, liberal, loving family as the government becomes increasingly totalitarian. Satrapi writes about the early influences in her life - her grandfather and uncle, both of whom fought for people's rights. She moves onto her teenage years in Vienna, struggling to come of age in a country so foreign to her upbringing and so far from her family. And then the difficulties of coming home to an Iran that was so different than what she remembered, and became increasingly difficult to deal with.

I loved this book. The artwork and the writing are seamlessly integrated, in such a manner that I highly recommend Persepolis as a starter comic if you are concerned about reading a comic and are not sure how to deal with the words and pictures. I am always concerned that I don't pay enough attention to the artwork in graphic novels, but in Persepolis, I had none of that concern:

I also feel like Satrapi does such a great job of showing us everyday Iranian life. She did the same thing in Embroideries, and I can see why people say that Persepolis is so much better than Embroideries. What I enjoyed about Embroideries was the rich, deep relationships that existed between the women in the book. And that is true x1000 in Persepolis. There is such a deep love between Satrapi and her parents, between Satrapi and her grandmother. And her whole family is so supportive of her - not just when she shows her brilliance, but also when she makes mistakes. And they never tell her to be afraid or to bow down to authority - they let her make her own decisions and live her own life and are very proud of her when she stands up for her rights.

This was truly a beautifully written, funny, and wonderful book. I am so glad that I finally read it, and I can't wait to read Satrapi's Chicken with Plums and perhaps watch the movie that she directed this year!

Monday, December 22, 2014

Review-itas: Life through the 20th century

Bud, Not Buddy, by Christopher Paul Curtis, is about a 10-year-old orphan boy living through the Great Depression in Michigan. Bud's mother passed away when he was six and he never knew his father. But in his suitcase filled with his most prized possessions, he has fliers that his mother saved over the years. The fliers show a jazz band, and Bud's sure that his father is in that band, so he sets off to go find him.

I read Curtis' The Mighty Miss Malone earlier this year and quickly decided that I should read all of his other books, on audiobook if possible. Bud, Not Buddy is my second Curtis book and Deza Malone even has a cameo!

I like the way Curtis writes about a black child's experience of the Great Depression. While the Great Depression was difficult for everyone, it was particularly hard on people of color who were passed over for jobs, often couldn't own property, and were discriminated against in many ways. I think Curtis does really well in bringing these important facts to life in ways that would make children curious to learn more and have a discussion with their parents or a teacher about how people experience the same world differently.

As with The Mighty Miss Malone, I liked how Curtis showed examples of different family structures. Bud is an orphan but has many happy memories of growing up with a single mom. He meets a stranger who is a proud father of a growing (and very fun) family, and a jazz band that acts as a family. While I didn't love Bud, Not Buddy as much as I did The Mighty Miss Malone, I did enjoy learning even more about the Great Depression and am looking forward to Curtis' perspective on other important historical events in American history.

Jacqueline Woodson's memoir in free verse, Brown Girl Dreaming, is set in the 1960s and moves from Ohio to South Carolina to New York. I did this book on audio. I do better with poetry in audio since I don't worry so much about whether I am getting the pacing and the rhythm right. Like pretty much everyone else, I loved it.

Woodson's stories tell of her early childhood growing up during a tumultuous time in American history, struggling with school, and falling in love with words and the art of story-telling. I wish I had read this in physical form because the poetry is stunning. I love the way Woodson confused facts and stories - she would hear something and then immediately incorporate that fact into a story about herself. It wasn't lying, it was learning the art of the story, and she excelled at it. This excerpt sums up very well the way I felt reading this book - I didn't want it to end, either:

“I am not my sister.

Words from the books curl around each other

make little sense

until

I read them again

and again, the story

settling into memory. Too slow my teacher says.

Read Faster.

Too babyish, the teacher says.

Read older.

But I don't want to read faster or older or

any way else that might

make the story disappear too quickly from where

it's settling

inside my brain,

slowly becoming a part of me.

A story I will remember

long after I've read it for the second, third,

tenth, hundredth time.”

Aya: Life in Yop City, by Marguerite Abouet and Clement Oubrerie is about 3 teenaged girls growing up in boom-time 1970s and 1980s Ivory Coast. Aya is dedicated to going to medical school and doesn't let anything distract her from that goal. Her friends Adjoua and Bintou, however, are more easily distracted. The three of them deal with a lot of family drama (seriously - everything from paternity drama to secret second family drama to homosexuality and everything in between).

I am a little torn about this book. On the surface, it's like a soap opera, with twists and turns on every level. I don't know much at all about what life is like in a polygamous society, but it seems very complicated! It was so interesting to learn about such a foreign culture, from the funeral parties to beauty pageant, from polygamy to witch doctors. Everything was new to me!

On another level, though, the book touches on some really important themes. For example, Aya wants to be a doctor, but her father just wants her to get married to some rich guy. Aya's girlfriends seem sexually liberated and like they just want to have fun in life, but they both deal with very real consequences of their promiscuity while the men seem to get off pretty easily. Aya's mother wrestles with the knowledge that her husband sleeps with many other women but gets very little sympathy because every man does that. And the two gay men in the book struggle with their homosexuality and what to do, knowing that they will never be accepted. And there are more examples of this - the beauty pageant, Aya's friend's impending marriage to a much older man, the catcalls every woman faces each time she walks down the street...

This is why I think perhaps the translation was a little lacking. The translator did a great job of getting the humor and wit across in each panel, but it was harder for me to understand the deeper issues and social commentary that were under the current here. Was Abouet just writing a fun drama? Or did she have more meaningful messages that she wanted to share? My opinion is that the latter is true (but I also probably look for feminism everywhere). In any case, this book is worth reading just for the immersion in another culture and the fantastic, vivid art. And, PS, it was made into an animated movie! I'll have to try and find it (with subtitles).

I read Curtis' The Mighty Miss Malone earlier this year and quickly decided that I should read all of his other books, on audiobook if possible. Bud, Not Buddy is my second Curtis book and Deza Malone even has a cameo!

I like the way Curtis writes about a black child's experience of the Great Depression. While the Great Depression was difficult for everyone, it was particularly hard on people of color who were passed over for jobs, often couldn't own property, and were discriminated against in many ways. I think Curtis does really well in bringing these important facts to life in ways that would make children curious to learn more and have a discussion with their parents or a teacher about how people experience the same world differently.

As with The Mighty Miss Malone, I liked how Curtis showed examples of different family structures. Bud is an orphan but has many happy memories of growing up with a single mom. He meets a stranger who is a proud father of a growing (and very fun) family, and a jazz band that acts as a family. While I didn't love Bud, Not Buddy as much as I did The Mighty Miss Malone, I did enjoy learning even more about the Great Depression and am looking forward to Curtis' perspective on other important historical events in American history.

Jacqueline Woodson's memoir in free verse, Brown Girl Dreaming, is set in the 1960s and moves from Ohio to South Carolina to New York. I did this book on audio. I do better with poetry in audio since I don't worry so much about whether I am getting the pacing and the rhythm right. Like pretty much everyone else, I loved it.

Woodson's stories tell of her early childhood growing up during a tumultuous time in American history, struggling with school, and falling in love with words and the art of story-telling. I wish I had read this in physical form because the poetry is stunning. I love the way Woodson confused facts and stories - she would hear something and then immediately incorporate that fact into a story about herself. It wasn't lying, it was learning the art of the story, and she excelled at it. This excerpt sums up very well the way I felt reading this book - I didn't want it to end, either:

“I am not my sister.

Words from the books curl around each other

make little sense

until

I read them again

and again, the story

settling into memory. Too slow my teacher says.

Read Faster.

Too babyish, the teacher says.

Read older.

But I don't want to read faster or older or

any way else that might

make the story disappear too quickly from where

it's settling

inside my brain,

slowly becoming a part of me.

A story I will remember

long after I've read it for the second, third,

tenth, hundredth time.”

Aya: Life in Yop City, by Marguerite Abouet and Clement Oubrerie is about 3 teenaged girls growing up in boom-time 1970s and 1980s Ivory Coast. Aya is dedicated to going to medical school and doesn't let anything distract her from that goal. Her friends Adjoua and Bintou, however, are more easily distracted. The three of them deal with a lot of family drama (seriously - everything from paternity drama to secret second family drama to homosexuality and everything in between).

I am a little torn about this book. On the surface, it's like a soap opera, with twists and turns on every level. I don't know much at all about what life is like in a polygamous society, but it seems very complicated! It was so interesting to learn about such a foreign culture, from the funeral parties to beauty pageant, from polygamy to witch doctors. Everything was new to me!