A month ago, I became an aunt to an adorable and winsome boy named Rishi. Around the same time, people started telling me about the book When Dimple Met Rishi, and I thought I would read the book and then maybe give it to my sister to read and imagine a fun future for her child.

When Dimple Met Rishi is about two Indian-American kids who go to an app development summer camp the summer between high school and college. Rishi and Dimple's parents are friends and want their children to meet and get married. Rishi is totally on-board with this, and he goes to Insomnia-con just to meet Dimple and propose (with his grandmother's ring, no less). Dimple has no idea; she's at Insomnia-con to develop an app to help people deal with diabetes. They meet, Rishi basically proposes, and Dimple freaks out. But then they get to know each other, and Dimple realizes that he's not all bad.

In general, I veer away from young adult romance because I find it too angsty and dramatic. I would never want to return to the period of my life when I was an overly-dramatic teenager, and it is hard for me to read books centered on characters at that age without rolling my eyes multiple times.

But I also grew up Indian-American, and I love that this book exists. There's an Indian girl on the cover, there are Hindi words in the text, there are Indian narrators on the audiobook (who pronounce all the names and words correctly!!!). All of these things are so great. It is like the YA romance version of Hasan Minhaj's Netflix special. I also appreciate that in this book, it's Dimple who is ambitious and driven and totally into being a techie, with big dreams on how to make it happen. And that Rishi loves art but feels like he needs to go to engineering school to make his parents happy.

Much about this book rings true, as someone who grew up here to Indian parents. One of my favorite parts, a tiny detail, was when Rishi explained to Dimple's friend that he speaks Hindi, but that he speaks a version of Hindi that is from Mumbai, where locals speak Marathi. And his parents went to Mumbai from elsewhere, as did many other people, and so the Hindi they speak is not often understood outside of Mumbai. This is so 100% true. My parents grew up in Bangalore, which is a Kannada-speaking city. But their families are both originally from Andhra, which is Telugu-speaking. But so many people from Andhra go to Bangalore that the version of Telugu they all speak is completely different than the Telugu spoken in Andhra. It's a small detail, but many Indian people live through it, and I loved that it somehow made its way into this book.

I also appreciate that the author, Sandhya Menon, made cultural pride and knowledge such a positive thing in this book. Rishi in particular is very well-versed in his heritage and has no embarrassment at all about fully embracing it. I think that is a really great lesson.

But there were also many things in this book that bothered me. Putting aside my general annoyance with young adult romance (and this book had many of those same tropes and bothers), there were things that just were too much for me. Granted, I am 100% sure that I would notice these and judge these more as an Indian than probably other people would. But they still grated.

For example, Rishi. He's this really perfect guy. He's extremely rich and goes to private school with other rich kids, but somehow he's not spoiled or bratty or entitled, even though all the other rich kids in this book totally are. This is never explained. Also, he is really smart and funny and kind. And he is an AMAZING artist who tells his dad that his "brain just doesn't work the same way" as an engineer's brain does. But... he somehow managed to get accepted to MIT, anyway, and is going there to major in computer engineering. Because THAT's an easy thing to just swing. Also, as a 17-year-old, he just shows up somewhere with his grandmother's engagement ring to propose marriage to a complete stranger and this strains credulity to me.

Also, Rishi had this whole encounter with this other Indian guy, Hari, that annoyed me. Hari was a jerk in the book, but there was one point when Rishi asked him where his parents were from (meaning, where in India) and Hari very pointedly said that his parents were born in the US. And then Rishi somehow "won" this competition by talking about how he was so happy and proud to go back to his family's home in India and really connect with his culture and background. This seemed to imply that somehow Hari was less Indian or less whatever than Rishi. This really bothered me because, personally, I despise when people ask me where I am from and then act as though my answer ("Chicago") is incorrect, as though they assume I am from somewhere else just because I am Indian. I realize that this question is different when asked by one Indian to another, but I completely understood Hari's anger in the situation, and I found Rishi's "I love my heritage and go to India all the time" holier-than-thou attitude pretty grating in that instance.

And then there's Dimple's relationship with her parents. Apparently, Dimple's mom wants her to wear Indian clothes all the time, even at school. (And Dimple does this, as there are multiple comments on her kurtas and odnis). And her mom wants her to wear a bunch of make-up and get married stat. Whereas Dimple wants to wear her glasses, no make-up, and focus on school. This part just never really rang true to me because it seemed like the author really wanted to set up this weird misunderstanding/antagonistic relationship between Dimple and her mom, but it was hard to believe in (as an adult, anyway) because her mom didn't come off that way at all, really, when you encountered her in the story. Maybe that's the way an adult would read the story, though, whereas a teenager would read it quite differently than I do :-)

The other thing about this book that just was off to me was the relationship between Rishi's brother, Ashish, and Dimple's friend, Celia. It felt like a waste of time and space to me, and I don't really think it needed to be included at all. Especially as I felt like the book dragged a bit at times with the plotting, and getting rid of that would have made it a bit tighter.

I think what frustrated me most was that it didn't quite rise as high above the Indian stereotypes as I would have liked. You still have two really good kids who do not rebel much at all against their parents. They both somehow get into Stanford and MIT (because God forbid they go to a place like UC-Berkeley or something). They watch Bollywood movies and, conveniently, perform in a talent show with a Bollywood dance number. And their parents want to arrange marriage for them at 18. Honestly, I'm surprised there wasn't a mention that Rishi had won the Scripps spelling bee as a child.

But! This book exists, and it is so proudly Indian-American, and it owns that culture, and I love that. I'm so glad that Dimple was going after her coding dreams and that Rishi had a great love for art, but I wish that it could have gone a bit further.

Showing posts with label #diversiverse. Show all posts

Showing posts with label #diversiverse. Show all posts

Sunday, August 6, 2017

Monday, July 31, 2017

Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid

I have read and enjoyed a few of Mohsin Hamid's novels on audiobook, and Exit West was no exception. The spare, sparse writing style that somehow builds to create beautiful, moving stories is present once more. Exit West is a novel about refugees and the impact of global migration on both the individuals and the world at large, and it's absolutely excellent.

Saeed and Nadia meet in an unnamed city, in an unnamed country. They become friends and fall in love, slowly and then hurriedly, as war overtakes their lives. They escape to Mykonos, and then to London, and then to San Francisco, through magical doorways that open up to people who can pay the price of entry.

Some people may be upset that Hamid reduces the entire exhausting, painful journey from a country in crisis to a country of refuge to the simple act of stepping through a doorway. After all, the decision to leave home is difficult, and then the trip from one place to another is often dangerous and horrible. But Hamid is not as interested in the process of becoming a refugee as on the impacts of being a refugee, or the impact of living in a world in which huge numbers of people migrate based on crises. Thus, Saeed and Nadia step over an edge and escape the physicality of their city, but they don't escape much else.

Exit West is an obviously timely novel in that it is about refugees. But timeliness in a story doesn't really matter if it doesn't stick; and in a story about refugees, it doesn't stick if it doesn't haunt you. I don't know if haunt is even the right word, but it is very difficult to read this novel without being just as consumed by the "what ifs?" as the characters are. What if I had never left? What if I brought my father with me? What if I had never met the person I escaped with? What if we escaped somewhere else? What would my life be like if war had never happened? What would I be like if war had never happened? It's impossible to know and equally impossible not to speculate.

Nadia is a confident, independent woman who adopts Saeed's family as her own and then has trouble removing herself from it. Saeed is an introspective, kind man who turns more and more to religion as he loses control of the trajectory of his life. They begin the story with so much promise and love and kindness for each other, but the stress of their lives causes both of them to draw back and recede from the other, to seek out friendship and understanding from others.

But there are other ways that people are impacted by the refugee crisis, and Hamid gives us brief snapshots of these lives before pulling away again. We see two old men fall in love over a piece of art. We see a man remake his life after contemplating suicide. We see, terrifyingly, a man follow two young women down the street as he strokes the knife in his pocket.

Exit West shows us how global migration can result in changes both profound and minimal to individuals, societies, and geographies. I loved how personal this story felt, from both Saeed's and Nadia's perspectives, and yet how easy it was to see just how much crises in completely foreign places can change people's behaviors here and everywhere. Definitely a book to read when you want to remind yourself of how important it is to remember that people are individuals, not statistics.

Saeed and Nadia meet in an unnamed city, in an unnamed country. They become friends and fall in love, slowly and then hurriedly, as war overtakes their lives. They escape to Mykonos, and then to London, and then to San Francisco, through magical doorways that open up to people who can pay the price of entry.

Some people may be upset that Hamid reduces the entire exhausting, painful journey from a country in crisis to a country of refuge to the simple act of stepping through a doorway. After all, the decision to leave home is difficult, and then the trip from one place to another is often dangerous and horrible. But Hamid is not as interested in the process of becoming a refugee as on the impacts of being a refugee, or the impact of living in a world in which huge numbers of people migrate based on crises. Thus, Saeed and Nadia step over an edge and escape the physicality of their city, but they don't escape much else.

Exit West is an obviously timely novel in that it is about refugees. But timeliness in a story doesn't really matter if it doesn't stick; and in a story about refugees, it doesn't stick if it doesn't haunt you. I don't know if haunt is even the right word, but it is very difficult to read this novel without being just as consumed by the "what ifs?" as the characters are. What if I had never left? What if I brought my father with me? What if I had never met the person I escaped with? What if we escaped somewhere else? What would my life be like if war had never happened? What would I be like if war had never happened? It's impossible to know and equally impossible not to speculate.

Nadia is a confident, independent woman who adopts Saeed's family as her own and then has trouble removing herself from it. Saeed is an introspective, kind man who turns more and more to religion as he loses control of the trajectory of his life. They begin the story with so much promise and love and kindness for each other, but the stress of their lives causes both of them to draw back and recede from the other, to seek out friendship and understanding from others.

But there are other ways that people are impacted by the refugee crisis, and Hamid gives us brief snapshots of these lives before pulling away again. We see two old men fall in love over a piece of art. We see a man remake his life after contemplating suicide. We see, terrifyingly, a man follow two young women down the street as he strokes the knife in his pocket.

Exit West shows us how global migration can result in changes both profound and minimal to individuals, societies, and geographies. I loved how personal this story felt, from both Saeed's and Nadia's perspectives, and yet how easy it was to see just how much crises in completely foreign places can change people's behaviors here and everywhere. Definitely a book to read when you want to remind yourself of how important it is to remember that people are individuals, not statistics.

Monday, July 24, 2017

Sea of Poppies

Here, she said, taste it. It is the star that took us from our homes and put us on this ship. It is the planet that rules our destiny.

- Deeti, describing a poppy seed

I have had Amitav Ghosh' Sea of Poppies on my radar since it was published. It's the first book in a trilogy centered on a ship, the Ibis. In the first book, the Ibis is transitioning from its previous life as a slave transporting vessel to one that transports coolies and opium. It begins its journey on the Ganges River in India, and then sets out on an ocean voyage with an amazingly rich cast of characters on board.

I loved this book. I am in absolute awe at the breadth and depth that is encompassed within its pages, and I am so excited to read the next two books in the series to see just how much more Ghosh has to share with me. There are some authors who truly astonish me with just how much they can pack into their pages - character development, plot advancement, social commentary, historical accuracy. It's books like this one that make reading a continued delight.

Sea of Poppies is set just at the start of the first Opium War. We don't learn much about the Opium Wars in the west (or at least not in the United States), so it was fascinating to learn more about a period that had such a massive impact on the world (and was a cause of World War I). The British Empire reeeeeeeally wanted China to open up to global trade, but the Chinese did not want to. This angered the British, and thus, Opium Wars. China was forced to cede Hong Kong and open up ports to global trade, and the British got to sell their stuff to more people. They also got access to indentured laborers (coolies) from Asia and South Asia since slavery was no longer an option for them.

Thus, Sea of Poppies is set just as globalization and imperialism really get their groove on, and the scope of this book is absolutely immense because of that. There are Indian farmers who are forced to grow poppies instead of food, and fall into debt. There is a mixed race American man trying to make his way in the world. There are pirates and merchant marines. There's an Indian raja who is humiliated by debt to the English, stripped of his title and wealth, and forced to go abroad as an indentured servant. There are, of course, the English, raking in great wealth and secure in their vision of bringing civilization to India and China. And there's more. The characters in this book are fantastic.

And those characters speak in a gloriously rich variety of languages. Honestly, this is where Ghosh's comedic genius really sparkles. Obviously, a book centered on a former slave ship that now transports opium can have many dark and depressing moments. But the way Ghosh uses language and shows how so many disparate languages can be combined and influence each other is so great. It took me a little while to understand some of the English spellings and mispronunciations of the Hindi words, but once I did, I usually smiled or laughed to myself. They were nice little Easter eggs for people who have some understanding of Indian language. I myself do not know Hindi, but am familiar enough with common words and names to have caught on. It was so well-done, and the book includes a glossary at the back for many of the words, too.

And with all of THAT happening, Ghosh doesn't ever lose sight of telling a fantastic story. Here is a very compelling tale about the wide-ranging impact of colonialism and imperialism, related through extremely personal stories. I loved that we get to know not only about how the Indian ruling class lost so much of its power and prestige to the British, but also get to learn about the farmers who suffered and the enterprising middle-class professionals who cashed out. I was thoroughly engrossed in learning more about how Hinduism was practiced in the 19th century, the obsessions with caste and purity and superstition, and how differently it is practiced today. Ghosh uses India as the setting, but the cast is from everywhere, all doing their best to make their way in a world. Most of the characters are pushing against rules and norms that have dictated their whole lives, whether due to race or caste or income or sex. And yet, they all come together on a ship and those rules are tested. You can see just how huge the social shifts in the 19th century were, all over the world, from societies of rigid class structures based on birth to more malleable ones based on wealth and influence. I loved that, and I loved this book. So excited to read the rest of this series!

- Deeti, describing a poppy seed

I have had Amitav Ghosh' Sea of Poppies on my radar since it was published. It's the first book in a trilogy centered on a ship, the Ibis. In the first book, the Ibis is transitioning from its previous life as a slave transporting vessel to one that transports coolies and opium. It begins its journey on the Ganges River in India, and then sets out on an ocean voyage with an amazingly rich cast of characters on board.

I loved this book. I am in absolute awe at the breadth and depth that is encompassed within its pages, and I am so excited to read the next two books in the series to see just how much more Ghosh has to share with me. There are some authors who truly astonish me with just how much they can pack into their pages - character development, plot advancement, social commentary, historical accuracy. It's books like this one that make reading a continued delight.

Sea of Poppies is set just at the start of the first Opium War. We don't learn much about the Opium Wars in the west (or at least not in the United States), so it was fascinating to learn more about a period that had such a massive impact on the world (and was a cause of World War I). The British Empire reeeeeeeally wanted China to open up to global trade, but the Chinese did not want to. This angered the British, and thus, Opium Wars. China was forced to cede Hong Kong and open up ports to global trade, and the British got to sell their stuff to more people. They also got access to indentured laborers (coolies) from Asia and South Asia since slavery was no longer an option for them.

Thus, Sea of Poppies is set just as globalization and imperialism really get their groove on, and the scope of this book is absolutely immense because of that. There are Indian farmers who are forced to grow poppies instead of food, and fall into debt. There is a mixed race American man trying to make his way in the world. There are pirates and merchant marines. There's an Indian raja who is humiliated by debt to the English, stripped of his title and wealth, and forced to go abroad as an indentured servant. There are, of course, the English, raking in great wealth and secure in their vision of bringing civilization to India and China. And there's more. The characters in this book are fantastic.

And those characters speak in a gloriously rich variety of languages. Honestly, this is where Ghosh's comedic genius really sparkles. Obviously, a book centered on a former slave ship that now transports opium can have many dark and depressing moments. But the way Ghosh uses language and shows how so many disparate languages can be combined and influence each other is so great. It took me a little while to understand some of the English spellings and mispronunciations of the Hindi words, but once I did, I usually smiled or laughed to myself. They were nice little Easter eggs for people who have some understanding of Indian language. I myself do not know Hindi, but am familiar enough with common words and names to have caught on. It was so well-done, and the book includes a glossary at the back for many of the words, too.

And with all of THAT happening, Ghosh doesn't ever lose sight of telling a fantastic story. Here is a very compelling tale about the wide-ranging impact of colonialism and imperialism, related through extremely personal stories. I loved that we get to know not only about how the Indian ruling class lost so much of its power and prestige to the British, but also get to learn about the farmers who suffered and the enterprising middle-class professionals who cashed out. I was thoroughly engrossed in learning more about how Hinduism was practiced in the 19th century, the obsessions with caste and purity and superstition, and how differently it is practiced today. Ghosh uses India as the setting, but the cast is from everywhere, all doing their best to make their way in a world. Most of the characters are pushing against rules and norms that have dictated their whole lives, whether due to race or caste or income or sex. And yet, they all come together on a ship and those rules are tested. You can see just how huge the social shifts in the 19th century were, all over the world, from societies of rigid class structures based on birth to more malleable ones based on wealth and influence. I loved that, and I loved this book. So excited to read the rest of this series!

Wednesday, July 5, 2017

The Best We Could Do

Sometimes I'll Google phrases like "best diverse comic books" and come across titles I've never heard of, such as this gem by Thi Bui, The Best We Could Do. Thi Bui was born in Vietnam and left the country with her family as a refugee during the war. They eventually made it to the United States, where Bui met her husband and they started a family. While raising her son, Bui reflected upon her relationships with her own parents and how little she knew about their lives before she entered the world. This graphic memoir is her attempt to tell their story and her own, and it's a beautiful one.

As I get older, it becomes more and more clear to me that my parents are human, and that they are humans who age. As I see my friends with their (still quite young) children, I can also see just how exhausting parenthood can be. There are few relationships in life that can remain as inherently selfish and self-absorbed as that of a child towards its parent. Even now, as an adult who is capable of doing adult things like cooking her own dinner and doing her own laundry, every time I go to my parents' house, I regress 100% and expect there to be food waiting for me when I arrive, and food ready for me to take back with me when I leave. I call my dad and complain of medical symptoms so that he will call in prescriptions for me. I call my mom and ask if she'll come over to oversee work on my house so that I don't have to take a day off of work.

Bui reflects upon this as she takes care of her son and compares her childhood to those of her parents' and her son's. Her parents came of age in vastly different circumstances; they met in college, got married, and then their world imploded. They raised children in the midst of war, and then left the country on a boat (while Bui's mother was eight months pregnant) to get to Malaysia. They arrived in America, still chased by their personal demons, and raised a family the best way they knew how. Bui struggled with her relationship with her parents, particularly her father, and only began to understand why when she learned more about their childhoods. The empathy that comes through in the way she describes her family history is so moving, and the title of the book works so well. Her parents weren't perfect, and they made mistakes. But they did the best they could do, and their children grew up with better lives, and their grandchildren grow up with even better ones.

The Best We Could Do is a beautiful story, particularly at this time when so much of the world is turning away refugees. Accepting refugees not only changes the lives of the refugees, but of generations to come. The book is also a truly heartfelt memoir about family and the deep love that you can have for people you don't always understand and who are far from perfect.

As I get older, it becomes more and more clear to me that my parents are human, and that they are humans who age. As I see my friends with their (still quite young) children, I can also see just how exhausting parenthood can be. There are few relationships in life that can remain as inherently selfish and self-absorbed as that of a child towards its parent. Even now, as an adult who is capable of doing adult things like cooking her own dinner and doing her own laundry, every time I go to my parents' house, I regress 100% and expect there to be food waiting for me when I arrive, and food ready for me to take back with me when I leave. I call my dad and complain of medical symptoms so that he will call in prescriptions for me. I call my mom and ask if she'll come over to oversee work on my house so that I don't have to take a day off of work.

Bui reflects upon this as she takes care of her son and compares her childhood to those of her parents' and her son's. Her parents came of age in vastly different circumstances; they met in college, got married, and then their world imploded. They raised children in the midst of war, and then left the country on a boat (while Bui's mother was eight months pregnant) to get to Malaysia. They arrived in America, still chased by their personal demons, and raised a family the best way they knew how. Bui struggled with her relationship with her parents, particularly her father, and only began to understand why when she learned more about their childhoods. The empathy that comes through in the way she describes her family history is so moving, and the title of the book works so well. Her parents weren't perfect, and they made mistakes. But they did the best they could do, and their children grew up with better lives, and their grandchildren grow up with even better ones.

The Best We Could Do is a beautiful story, particularly at this time when so much of the world is turning away refugees. Accepting refugees not only changes the lives of the refugees, but of generations to come. The book is also a truly heartfelt memoir about family and the deep love that you can have for people you don't always understand and who are far from perfect.

Labels:

#diversiverse,

20th century,

america,

family,

far east,

war

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

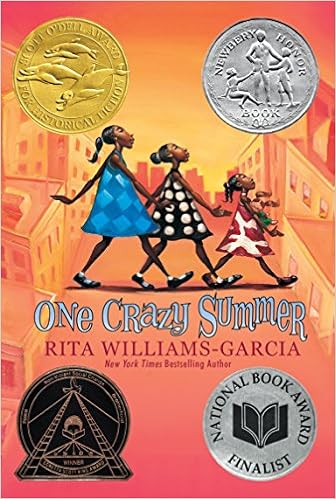

Rita Williams-Garcia's One Crazy Summer

I first heard about the book One Crazy Summer, by Rita Williams-Garcia, on Ana's blog in 2014. Me being me, I read the book in 2017. So I'm a little late to the party, but the party is still excellent!

I first heard about the book One Crazy Summer, by Rita Williams-Garcia, on Ana's blog in 2014. Me being me, I read the book in 2017. So I'm a little late to the party, but the party is still excellent!One Crazy Summer is set during the summer of 1968. Delphine and her sisters are shipped from their home with their father and grandmother in Brooklyn, New York to stay with their mother (who emphatically did not want them) in Oakland, California. Their mother, Cecile, is pretty eccentric and hands-off, so Delphine and her sisters spend much of their time in a summer camp run by the Black Panthers, learning about civil rights, strength, and unity.

Williams-Garcia's note at the end of the book emphasized that there were children also involved in the fight for civil rights, and this book is a brilliant way of showing that involvement. It's also about as complex as a children's novel can be about familial baggage. Cecile left her family and took off for the other side of the country. She isn't motherly or very caring at all in the book, to the extent that the resolution at the end felt a little forced to me. But as an adult reading the book, it's easy to empathize with her and her desire to make her own choices and live her own life. Serious kudos to Williams-Garcia for making Cecile a complex, complete person with her own struggles and motivations, some of which are unrelated to her role as a wife or mother or caregiver.

And Delphine and her sisters are wonderful. I loved the way they stick together and then bicker and then come together again. I love how they all know each other so well but continue to surprise and challenge each other. I love that they all just got up and went to San Francisco together for a day on their own. I loved the sweetness of Delphine letting herself go one moment to scream with joy as she goes down a big hill, instead of always being the grown-up.

One of my favorite things about this book is the way it portrayed the Black Panthers. This is not the paramilitary, extremist organization that many people learn about in school. It's one that provided free meals in neighborhoods and organized summer camps that taught children that they were important and valued.

I read this book for a bit of lighthearted fun after so many heavy, difficult books over the past few months. It was so easy to read and so lovely, but it certainly has depth and more heart and kindness than you would expect in such a slim, quick read. I can't wait to continue the series!

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

Trevor Noah's Born a Crime

I don't watch The Daily Show very often, mostly because I don't watch TV all that often. I didn't know much at all about Trevor Noah when he took over after Jon Stewart left. I have only watched a few episodes since then, and Noah's style is very different. He's much less angry, more willing to seek common ground. That's not to say that Jon Stewart was too jaded for his job, but you could see it wear on him, every day talking about important topics but not seeming to make any real difference.

I became interested in reading Trevor Noah's memoir, Born a Crime, after listening to some interviews with him when the book came out. I liked many of the things he said, and the very genuine way in which he said them. He does want to connect with people and find the many ways in which we are alike and can share moments and experiences vs harping on details that can tear us apart. I appreciate this kindness and empathy in him, particularly as he is someone who works in comedy and late night and news media that depends on ratings.

Noah's book is about his childhood and early adulthood in South Africa. It's not exhaustive; there are clearly some episodes that are quite painful and he does not dwell on those. It is more episodic in nature; the only people we get to know well and who feature prominently through the entire book are Trevor and his mother. Noah's mother seems like an amazing woman. She is deeply religious, and Trevor grew up going to multiple churches multiple days a week. She is also fiercely independent. She chose to live on her own in a dangerous city and have a mixed race child out of wedlock while living under apartheid. She raised him to believe that he could do anything. She worked and worked and worked, and when she married someone, she married an abusive alcoholic and the police never once helped to keep her safe.

Honestly, having read this book, the only word I can possibly use to describe Trevor Noah and his mom is resilient. Noah grew up in a very, very difficult environment. His family was extremely poor, he often went hungry, he was a mixed race kid in a country that was obsessed with race, and there seemed to be very little stability in his life. And yet he seems never to have lost his kindness and gentleness. This book makes me want to watch The Daily Show because I want to support empathy. It makes me respect religion and deeply religious people more because when religion is done right, it really can make people strive to become better, kinder versions of themselves.

I don't think I finished this book knowing Trevor Noah any better than I did going into it. I understand his background and his life better, but I do think he holds the reader just a little bit away. I think he has a lot of painful memories, and I don't think he wants to revisit them or dwell on them too deeply. Instead, he writes about events that shaped his thinking and who he became. He talks about the help he received and how grateful he is for that help and acknowledges that a lot of people don't get help. He talks about his mother and the moment he realized that women are often much more vulnerable than men in a situation. He talks about the time he realized that the police aren't always great people, that they are human and come into situations with their own histories and biases. And through it all, he shows readers (as kindly and diplomatically as possible) why he believes what he believes.

A quote that exemplifies what I am trying to explain above about Noah's approach:

I became interested in reading Trevor Noah's memoir, Born a Crime, after listening to some interviews with him when the book came out. I liked many of the things he said, and the very genuine way in which he said them. He does want to connect with people and find the many ways in which we are alike and can share moments and experiences vs harping on details that can tear us apart. I appreciate this kindness and empathy in him, particularly as he is someone who works in comedy and late night and news media that depends on ratings.

Noah's book is about his childhood and early adulthood in South Africa. It's not exhaustive; there are clearly some episodes that are quite painful and he does not dwell on those. It is more episodic in nature; the only people we get to know well and who feature prominently through the entire book are Trevor and his mother. Noah's mother seems like an amazing woman. She is deeply religious, and Trevor grew up going to multiple churches multiple days a week. She is also fiercely independent. She chose to live on her own in a dangerous city and have a mixed race child out of wedlock while living under apartheid. She raised him to believe that he could do anything. She worked and worked and worked, and when she married someone, she married an abusive alcoholic and the police never once helped to keep her safe.

Honestly, having read this book, the only word I can possibly use to describe Trevor Noah and his mom is resilient. Noah grew up in a very, very difficult environment. His family was extremely poor, he often went hungry, he was a mixed race kid in a country that was obsessed with race, and there seemed to be very little stability in his life. And yet he seems never to have lost his kindness and gentleness. This book makes me want to watch The Daily Show because I want to support empathy. It makes me respect religion and deeply religious people more because when religion is done right, it really can make people strive to become better, kinder versions of themselves.

I don't think I finished this book knowing Trevor Noah any better than I did going into it. I understand his background and his life better, but I do think he holds the reader just a little bit away. I think he has a lot of painful memories, and I don't think he wants to revisit them or dwell on them too deeply. Instead, he writes about events that shaped his thinking and who he became. He talks about the help he received and how grateful he is for that help and acknowledges that a lot of people don't get help. He talks about his mother and the moment he realized that women are often much more vulnerable than men in a situation. He talks about the time he realized that the police aren't always great people, that they are human and come into situations with their own histories and biases. And through it all, he shows readers (as kindly and diplomatically as possible) why he believes what he believes.

A quote that exemplifies what I am trying to explain above about Noah's approach:

People love to say, "Give a man a fish, and he'll eat for a day. Teach a man to fish, and he'll eat for a lifetime." What they don't say is, "And it would be nice if you gave him a fishing rod." That's the part of the analogy that's missing. Working with Andrew was the first time in my life I realized you need someone from the privileged world to come to you and say, "Okay, here's what you need, and here's how it works." Talent alone would have gotten me nowhere without Andrew giving me the CD writer. People say, "Oh, that's a handout." No. I still have to work to profit by it. But I don't stand a chance without it.This was an excellent book, and I bought a copy for my keeper shelf. Highly recommended.

Labels:

#diversiverse,

africa,

biography,

contemporary,

family,

non-fiction,

race

Monday, April 17, 2017

Whatever happened to interracial love?

I heard about Kathleen Collins and her collection of short stories, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, in the New York Times Book Review, where I get many of my reading recommendations (and which has gotten better at reviewing books by people who are not white and male). Kathleen Collins was active in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, but most of her artistic work (films, plays, short stories) was produced in the 1980s. Her short stories were, for the most part, never published. Her daughter discovered them in a trunk.

It's always hard to judge artistic talent by stories left unpublished in a trunk, mainly because it's hard to know if these stories were complete or if the author still wanted to work on them. But the romance of the whole situation is just too much to pass up! Undiscovered author! A trunk! The perfect cultural moment! Stories on race, gender, sexuality! It's a lot of awesomeness. If it could happen for Emily Dickinson, can't it happen for other people, too?

I think it can, sometimes. But sometimes the collection can also be pretty inconsistent. I think that's true for Kathleen Collins. There is so much wit in her stories, so much that speaks to how fascinating and vibrant she must have been, how much fun she must have been to talk to. But there are other stories that feel unrefined or directionless. Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is more a collection of what was great potential, lost too early (Collins died of cancer in 1988 at age 46).

The stories are mainly pretty short, and race is alluded to in almost all of them. One story is told from the point of view of a man describing the perfect family, a close-knit unit that was beautiful, intelligent, and got along well. But then cracks start to show, and it turns out the family's future is not nearly as happy as one would hope. In another, a woman loyally sends letters and gifts to her husband in prison. When he gets out and moves to a foreign country (without her), she finds peace in a small, rural home and some new friends. In "The Uncle," the narrator relates the story of his uncle, who is ill and whom many describe as lazy for his whole life. But the narrator, upon reflection, thinks that his uncle was a hero, just for surviving..

It's always hard to judge artistic talent by stories left unpublished in a trunk, mainly because it's hard to know if these stories were complete or if the author still wanted to work on them. But the romance of the whole situation is just too much to pass up! Undiscovered author! A trunk! The perfect cultural moment! Stories on race, gender, sexuality! It's a lot of awesomeness. If it could happen for Emily Dickinson, can't it happen for other people, too?

I think it can, sometimes. But sometimes the collection can also be pretty inconsistent. I think that's true for Kathleen Collins. There is so much wit in her stories, so much that speaks to how fascinating and vibrant she must have been, how much fun she must have been to talk to. But there are other stories that feel unrefined or directionless. Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is more a collection of what was great potential, lost too early (Collins died of cancer in 1988 at age 46).

The stories are mainly pretty short, and race is alluded to in almost all of them. One story is told from the point of view of a man describing the perfect family, a close-knit unit that was beautiful, intelligent, and got along well. But then cracks start to show, and it turns out the family's future is not nearly as happy as one would hope. In another, a woman loyally sends letters and gifts to her husband in prison. When he gets out and moves to a foreign country (without her), she finds peace in a small, rural home and some new friends. In "The Uncle," the narrator relates the story of his uncle, who is ill and whom many describe as lazy for his whole life. But the narrator, upon reflection, thinks that his uncle was a hero, just for surviving..

But his weeping, wailing, and gnashing of teeth brimmed potent to overflowing in the room, and I began to weep for him, weep tears of pride and joy that he should have so soaked his life in sorrow and gone back to some ancient ritual beyond the blunt humiliation of his skin, with its bound-and-sealed possibilities; so refused to overcome his sorrow as some affliction to be transcended, some stumbling block put in his way for the sake of trial and endurance; so refused to strike out against it, go down in a blaze of responsibilities met and struggled with. No. He utterly honored his sorrow, gave in to it with such deep and boundless weeping that it seemed as I stood there he was the bravest man I had ever known.There was silver and gold in all the stories collected here, even if all of them didn't stick with me. So much about how difficult life can be when people expect so little of you, or treat you like you are less than what you know yourself to be. So much about the struggle to understand your parents or your children, about competing priorities for different generations and what they decide is worth fighting for. It's a lovely collection and well worth seeking out. Not only because it's amazing to discover the unknown work of a feminist civil rights cultural icon, but because the stories are quite good, too.

Wednesday, April 5, 2017

Women Culture and Politics

Women Culture and Politics is the first Angela Y Davis book I've ever read. For those of you who may not know, Angela Davis is a hugely influential feminist communist activist. She was very active in the 1960s with the Civil Rights movement, fought hard against Ronald Reagan when he was governor of California and when he was president, and continues to serve as a voice of resistance and strength.

Women Culture and Politics is a collection of Davis' essays and speeches from the 1980s and 1990s. I am not sure if it is the best book to start with, but I think this is mostly due to the format. I admit that my grasp of history from the 1980s and 1990s is not quite as extensive as I would like, and Davis' essays are very much commentary on the times. I wish that there was an introduction to the collection as a whole or to each specific essay so that I had a better grasp and understanding of the context in which she was writing the essay or delivering the speech. That would have helped me a lot to fully understand Davis' points.

[Side note: That said, I really need to learn more about the entire Reagan presidency. Does anyone have a book they recommend for that? I feel like Reagan comes up a LOT these days, and I would like to understand more of our history with Russia and Latin America and all the rest. So, please let me know if there is any book you think would be a good one to get some background!]

While some of the context of Davis' points was lost on me, a concerning number of points were still very relevant. I suppose in the grand scheme of things, 30 years is not so long a time in which to make real change in society. But it still feels depressing.

One thing Davis talked about in her essays comes up a lot in liberal discussion these days. And that is identity politics. I have been very up and down on identity politics and the impact of identity politics on our election and on the way people describe themselves now. I 100% believe that people should feel comfortable being their truest, best selves, and that they should feel safe enough to be open about who they are. But I also can feel exhausted by the number of identifiers everyone feels the need to use these days. And I am very concerned by the way identity politics has led to white nationalism and supremacy. Davis' approach to this is that everyone should come together.

There is a LOT in this book that is amazing. I folded so many pages down to note down quotes. It would be too much for me to share them all with you, so I recommend that instead, you just read the book and feel all the feels and become a Davis fangirl. I plan to read much more by her, and I look forward to the way she will challenge my thinking.

Women Culture and Politics is a collection of Davis' essays and speeches from the 1980s and 1990s. I am not sure if it is the best book to start with, but I think this is mostly due to the format. I admit that my grasp of history from the 1980s and 1990s is not quite as extensive as I would like, and Davis' essays are very much commentary on the times. I wish that there was an introduction to the collection as a whole or to each specific essay so that I had a better grasp and understanding of the context in which she was writing the essay or delivering the speech. That would have helped me a lot to fully understand Davis' points.

[Side note: That said, I really need to learn more about the entire Reagan presidency. Does anyone have a book they recommend for that? I feel like Reagan comes up a LOT these days, and I would like to understand more of our history with Russia and Latin America and all the rest. So, please let me know if there is any book you think would be a good one to get some background!]

While some of the context of Davis' points was lost on me, a concerning number of points were still very relevant. I suppose in the grand scheme of things, 30 years is not so long a time in which to make real change in society. But it still feels depressing.

One thing Davis talked about in her essays comes up a lot in liberal discussion these days. And that is identity politics. I have been very up and down on identity politics and the impact of identity politics on our election and on the way people describe themselves now. I 100% believe that people should feel comfortable being their truest, best selves, and that they should feel safe enough to be open about who they are. But I also can feel exhausted by the number of identifiers everyone feels the need to use these days. And I am very concerned by the way identity politics has led to white nationalism and supremacy. Davis' approach to this is that everyone should come together.

"...we must begin to merge that double legacy in order to create a single continuum, one that solidly represents the aspirations of all women in our society. We must begin to create a revolutionary, multiracial women's movement that seriously addresses the main issues affecting poor and working-class women."This comes up again and again in Davis' writing, this idea that rich, white women seem to fight a completely different battle than working class women of color, and that they often forget to fight for the rights of people who are not as well off as they are. This is still relevant today, and it came up a lot with the Women's March on Washington and it continues to come up with women's rights now when we talk about Planned Parenthood (which we seem to talk about all the time). It continues now as people obsess over the rural white vote. I feel like there must be a way to talk about the issues in ways that are less divisive but that doesn't make people feel left behind. But do we all just jump too quickly now to take offense, to say, "What about me? You mentioned everyone's suffering but mine!" And instead of giving a person the opportunity to go back and consider and grow, we assume the worst and shame the person and then the person gets so nervous about saying anything wrong, but doesn't actually change his/her inner thoughts. Just hides them. And then we are where we are.

There is a LOT in this book that is amazing. I folded so many pages down to note down quotes. It would be too much for me to share them all with you, so I recommend that instead, you just read the book and feel all the feels and become a Davis fangirl. I plan to read much more by her, and I look forward to the way she will challenge my thinking.

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

The Association of Small Bombs

Karan Mahajan's The Association of Small Bombs is one of those books that is very popular with critics. It's also one of those books that you read and know that is it incredibly well-written and has a really strong message. It tackles huge issues in a very personal way. I am very glad that I read it, but I don't think I will read it again because it is so profoundly sad.

The Association of Small Bombs starts with a "small" terrorist attack in New Delhi in 1996. Two brothers are among the victims. Their friend, Mansoor, survives with a strain in his wrist.

The book follows the brothers' parents, Mansoor and his parents, and the terrorist who committed the attack (and the progress of a terrorist in the making) over the next several years. We see the way the parents come together and then drift apart. The way Mansoor's parents are overprotective and then feel like they are losing their son. The way Mansoor first feels so lucky to have survived and works hard to make the most of it, and then slowly loses that momentum.

While I found this book quite depressing, there were things that I also found very valuable in it. I appreciated that Mahajan focused on a "smaller" terrorist act in India vs on a "major" one in the west. Just as Americans seem to have become inured to mass shootings (which is horrifying), much of the world seems to think that terrorist attacks in certain parts of the world are totally normal. But Mahajan shows readers that senseless violence is never normal to the people who experience it and have to deal with its consequences, no matter how regularly it may happen. He shows how difficult it can be for parents to recover from the randomness of an act, to rethink so many decisions, to see their lives go down a completely different path than the one they had set out on themselves. Similarly, he shows how survivors can continue to suffer even when it seems like they have minor injuries. When you consider how many of these small bombs have detonated in the world, and how many lives they have upended, you can imagine that there are countless people whose lives have been profoundly changed by acts committed by complete strangers who don't care about them at all.

I also appreciated that Mahajan did not focus on an extremist Muslim's hatred of western influence. He focused on an internal Indian issue - Kashmir. This is important because so many people (*white* people, mainly) seem to think that the only victims of terrorists are westerners and that terrorists are all brown people against white people. This is not the case. Terrorists and their victims are of all races and beliefs and walks of life. It may be difficult for some readers to understand the political background that informs this part of the book (I certainly had some trouble), but I don't know that it matters - what matters is that people believe in something enough to commit desperate acts in its honor. Or they feel trapped that they have no other option.

And that was the last thing about this book that I appreciated. It really takes you inside the mind of someone as he veers from a path of non-violence to one of extreme action. It's difficult to see this happen, especially with a character you liked. But it's important, too, to understand that people are motivated to actions by many different things. It's not always a belief in extremism. A lot of times, people feel trapped or forced into an action. Or they feel they have no one to talk to, they have no real future. That's not to justify committing an act of violence, but more to show that circumstances can inform our life decisions more than we are often willing to admit.

But, as I said earlier, this is a tough book to read. It's supposed to be a tough book. Make sure you have a chaser for it.

The Association of Small Bombs starts with a "small" terrorist attack in New Delhi in 1996. Two brothers are among the victims. Their friend, Mansoor, survives with a strain in his wrist.

The book follows the brothers' parents, Mansoor and his parents, and the terrorist who committed the attack (and the progress of a terrorist in the making) over the next several years. We see the way the parents come together and then drift apart. The way Mansoor's parents are overprotective and then feel like they are losing their son. The way Mansoor first feels so lucky to have survived and works hard to make the most of it, and then slowly loses that momentum.

While I found this book quite depressing, there were things that I also found very valuable in it. I appreciated that Mahajan focused on a "smaller" terrorist act in India vs on a "major" one in the west. Just as Americans seem to have become inured to mass shootings (which is horrifying), much of the world seems to think that terrorist attacks in certain parts of the world are totally normal. But Mahajan shows readers that senseless violence is never normal to the people who experience it and have to deal with its consequences, no matter how regularly it may happen. He shows how difficult it can be for parents to recover from the randomness of an act, to rethink so many decisions, to see their lives go down a completely different path than the one they had set out on themselves. Similarly, he shows how survivors can continue to suffer even when it seems like they have minor injuries. When you consider how many of these small bombs have detonated in the world, and how many lives they have upended, you can imagine that there are countless people whose lives have been profoundly changed by acts committed by complete strangers who don't care about them at all.

I also appreciated that Mahajan did not focus on an extremist Muslim's hatred of western influence. He focused on an internal Indian issue - Kashmir. This is important because so many people (*white* people, mainly) seem to think that the only victims of terrorists are westerners and that terrorists are all brown people against white people. This is not the case. Terrorists and their victims are of all races and beliefs and walks of life. It may be difficult for some readers to understand the political background that informs this part of the book (I certainly had some trouble), but I don't know that it matters - what matters is that people believe in something enough to commit desperate acts in its honor. Or they feel trapped that they have no other option.

And that was the last thing about this book that I appreciated. It really takes you inside the mind of someone as he veers from a path of non-violence to one of extreme action. It's difficult to see this happen, especially with a character you liked. But it's important, too, to understand that people are motivated to actions by many different things. It's not always a belief in extremism. A lot of times, people feel trapped or forced into an action. Or they feel they have no one to talk to, they have no real future. That's not to justify committing an act of violence, but more to show that circumstances can inform our life decisions more than we are often willing to admit.

But, as I said earlier, this is a tough book to read. It's supposed to be a tough book. Make sure you have a chaser for it.

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

Review-itas: Books that confused me

Guys, Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee confused me so much that I cannot even explain the cover of this book to you. Does it fit with the story? I don't know. I mean, the story takes place in space, so that part is accurate. But what is the spiky thing that dominates the image? I don't know.

As far as I can tell, Ninefox Gambit is set in a civilization that really likes order. There appears to be a massive mathematical algorithm (the "calendar") that oversees every tiny thing, especially in the military. Possibly people exist outside of the military, but it is hard to tell. There is also a very rigid caste system in place, with different groups of people going into different areas of study and conforming to very specific traits. The main character, Cheris, is in the military leading her team and somehow goes against the calendar. This means she's in trouble and she's given a very big, basically impossible task to go kill some heretics, for which she asks for help from this undead ghost who won every battle he ever fought, except he also turned traitor and got an obscene number of people killed.

There was a lot in this book that I did not understand. This book is like all my fears and feelings of intimidation about science fiction coming to fruition. Once I got to the end and things started moving a little faster and became more people-focused than calendar-focused (I still cannot grasp this calendar system, and it DRIVES ME CRAZY), I got more into it. And it certainly ends on a high note that bodes well for the series to follow. So I eventually got the high-level plot, but I could tell you nothing about the setting.

After my appalling showing in 2016 of reading only four books off my TBR list, I was determined to do better in 2017. (To be fair, I set a pretty low bar for myself, so I feel confident I can beat it.) I read and enjoyed Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber, so I decided to give Sister Mine a go. Many of the same elements that I loved in Midnight Robber are present here - a strong cultural identity, humor, and fantastic female characters at the center. Sister Mine is often compared to American Gods or Anansi Gods because it is about a family of demigods. But whereas Neil Gaiman's book is almost entirely about men, Hopkinson's puts women very much at the center of the story. She plays with gender, sexuality, and many other themes while she wreaks havoc with the lives of both humans and gods.

I listened to Sister Mine on audio, and the narrator is excellent. I don't listen to many audiobooks any more, but I was pretty much instantly drawn into this one. I enjoyed many things about this story, but parts of it were just a bit too out there for me, particularly towards the end when things became very convoluted to me. I really liked many of the characters in this book, but with about two hours to go, I was just ready for the book to end. There were plot points that came up that didn't make a ton of sense to me or fit into the rest of the story, and then there was this whole section at the end that I was just... I don't know what was happening. I feel like maybe if I were reading a physical copy of the book instead of listening to an audiobook, it would have been easier for me to understand what was happening. Or maybe I'm just so confused by the real world that fantastical and science fiction worlds go too far for me. Regardless, this was a lighter book than Midnight Robber for sure, with humor and pretty great family dynamics. So if you want to give Hopkinson a try but don't want all the heavy stuff, this could be a good one to start with. But I wouldn't say it's as strong as Midnight Robber.

As far as I can tell, Ninefox Gambit is set in a civilization that really likes order. There appears to be a massive mathematical algorithm (the "calendar") that oversees every tiny thing, especially in the military. Possibly people exist outside of the military, but it is hard to tell. There is also a very rigid caste system in place, with different groups of people going into different areas of study and conforming to very specific traits. The main character, Cheris, is in the military leading her team and somehow goes against the calendar. This means she's in trouble and she's given a very big, basically impossible task to go kill some heretics, for which she asks for help from this undead ghost who won every battle he ever fought, except he also turned traitor and got an obscene number of people killed.

There was a lot in this book that I did not understand. This book is like all my fears and feelings of intimidation about science fiction coming to fruition. Once I got to the end and things started moving a little faster and became more people-focused than calendar-focused (I still cannot grasp this calendar system, and it DRIVES ME CRAZY), I got more into it. And it certainly ends on a high note that bodes well for the series to follow. So I eventually got the high-level plot, but I could tell you nothing about the setting.

After my appalling showing in 2016 of reading only four books off my TBR list, I was determined to do better in 2017. (To be fair, I set a pretty low bar for myself, so I feel confident I can beat it.) I read and enjoyed Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber, so I decided to give Sister Mine a go. Many of the same elements that I loved in Midnight Robber are present here - a strong cultural identity, humor, and fantastic female characters at the center. Sister Mine is often compared to American Gods or Anansi Gods because it is about a family of demigods. But whereas Neil Gaiman's book is almost entirely about men, Hopkinson's puts women very much at the center of the story. She plays with gender, sexuality, and many other themes while she wreaks havoc with the lives of both humans and gods.

I listened to Sister Mine on audio, and the narrator is excellent. I don't listen to many audiobooks any more, but I was pretty much instantly drawn into this one. I enjoyed many things about this story, but parts of it were just a bit too out there for me, particularly towards the end when things became very convoluted to me. I really liked many of the characters in this book, but with about two hours to go, I was just ready for the book to end. There were plot points that came up that didn't make a ton of sense to me or fit into the rest of the story, and then there was this whole section at the end that I was just... I don't know what was happening. I feel like maybe if I were reading a physical copy of the book instead of listening to an audiobook, it would have been easier for me to understand what was happening. Or maybe I'm just so confused by the real world that fantastical and science fiction worlds go too far for me. Regardless, this was a lighter book than Midnight Robber for sure, with humor and pretty great family dynamics. So if you want to give Hopkinson a try but don't want all the heavy stuff, this could be a good one to start with. But I wouldn't say it's as strong as Midnight Robber.

Monday, January 9, 2017

The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson

I took advantage of having a big chunk of free time off work between Christmas and New Year's to tackle a big, meaty book. I saw Isabel Wilkerson speak during the Chicago Humanities Festival after the election in November, and I had a feeling that her book would be a great one for me to read to start the new year.

The Warmth of Other Suns is about the Great Migration, the movement of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North over several decades in the 20th century. Wilkerson conducted hundreds of interviews. Her book compiles many people's stories, though she focuses on three people who left various areas of the South at different times and went to New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles to start new lives.

This book is excellent. It is 540 pages of personal stories, which probably sounds like a lot, but it is not. It feels like you are in the same room as these people as they tell you about their lives, the decisions they made, the regrets they have, the people they knew. It's almost like a gigantic, written version of This American Life.

Like many people, I am struggling to come to grips with the way the world seems to be moving backwards to tribalism, distrust, and fear. Reading Wilkerson's book was empowering. When she came to speak at the Humanities Festival, she said something that I keep going back to. I am paraphrasing, but the gist of it was, "The lesson of the Great Migration is the power of an individual choice. They freed themselves."

Often, when reading books about minorities in the US, the general trend of stories is the same. People who are different show up. The people who are already there become angry. They treat the newcomers badly (sometimes, really really badly). The newcomers fight for their rights. Sometimes they win. It's an important story to tell because it happens so consistently, probably everywhere, but definitely in the United States. But it's also just depressing and disheartening. People are so frightened by anything that is different, no matter how superficial that difference might be, or no matter how ridiculous that fear is. And they fight back in terrifying, brutal ways.

But even against all that, a backdrop of hate and threats and physical violence, people fight. And that's what was so, so wonderful about this book. Even people with very little of their own, barely scraping by and with no rights of their own - they resisted and they fought and they made the world a more accepting and welcoming and equal place for all of us. As Wilkerson said, "The Great Migration... was a step in freeing not just the people who fled, but the country whose mountains they crossed... It was, if nothing else, an affirmation of the power of an individual decision, however powerless the individual might appear on the surface."

A few snapshots from this book really stood out to me:

1. Ida Mae Gladney coming to Chicago in the 1930s and realizing that she had the opportunity and the right to vote and that her vote would be heard and counted. She had never even bothered trying to vote before. Many, many years later, she would vote for Barack Obama for Illinois state senator.

2. Robert Foster's desperate search for a motel to spend the night on his drive to his new life in Los Angeles. He went from motel to motel and was denied a room at every single one. Finally, he broke down and told one couple that he was a veteran, that he was a physician, that he meant no harm to anyone and just wanted to sleep. They still refused.

3. The story of a man who worked with the NAACP, was locked up in a mental institution, and then escaped with the help of a coordinated effort that had him in a coffin and traveling across state lines in different hearses.

4. The store clerk who owned a dog and taught that dog many tricks. One trick was for the clerk to ask the dog if he'd rather be black or dead. The dog was trained to respond by rolling over and playing dead.

There were many more stories about oppression and resistance, the times people bowed to authority and the times they defied it. The many ways that people faced indignities and swallowed the insults, turned the other cheek, and then came back to fight another round. The consequences of leaving behind family and friends to start a new life. The consequences of working long, hard hours to make a better life for a family that you rarely get to see. The consequences of moving from the rural south to the industrial north.

I don't think I've done a good job of describing why this book is so moving. But it's a huge book, and it covers so much! It's hard to cover all of that in one post. All I can say is that it is an excellent story of how much progress we've made and the cost of that progress, not only for the country as a whole but for so many individual people. And it serves as an important reminder that individual decisions matter and can make a difference in the world.

The Warmth of Other Suns is about the Great Migration, the movement of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North over several decades in the 20th century. Wilkerson conducted hundreds of interviews. Her book compiles many people's stories, though she focuses on three people who left various areas of the South at different times and went to New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles to start new lives.

This book is excellent. It is 540 pages of personal stories, which probably sounds like a lot, but it is not. It feels like you are in the same room as these people as they tell you about their lives, the decisions they made, the regrets they have, the people they knew. It's almost like a gigantic, written version of This American Life.

Like many people, I am struggling to come to grips with the way the world seems to be moving backwards to tribalism, distrust, and fear. Reading Wilkerson's book was empowering. When she came to speak at the Humanities Festival, she said something that I keep going back to. I am paraphrasing, but the gist of it was, "The lesson of the Great Migration is the power of an individual choice. They freed themselves."

Often, when reading books about minorities in the US, the general trend of stories is the same. People who are different show up. The people who are already there become angry. They treat the newcomers badly (sometimes, really really badly). The newcomers fight for their rights. Sometimes they win. It's an important story to tell because it happens so consistently, probably everywhere, but definitely in the United States. But it's also just depressing and disheartening. People are so frightened by anything that is different, no matter how superficial that difference might be, or no matter how ridiculous that fear is. And they fight back in terrifying, brutal ways.

But even against all that, a backdrop of hate and threats and physical violence, people fight. And that's what was so, so wonderful about this book. Even people with very little of their own, barely scraping by and with no rights of their own - they resisted and they fought and they made the world a more accepting and welcoming and equal place for all of us. As Wilkerson said, "The Great Migration... was a step in freeing not just the people who fled, but the country whose mountains they crossed... It was, if nothing else, an affirmation of the power of an individual decision, however powerless the individual might appear on the surface."

A few snapshots from this book really stood out to me:

1. Ida Mae Gladney coming to Chicago in the 1930s and realizing that she had the opportunity and the right to vote and that her vote would be heard and counted. She had never even bothered trying to vote before. Many, many years later, she would vote for Barack Obama for Illinois state senator.

2. Robert Foster's desperate search for a motel to spend the night on his drive to his new life in Los Angeles. He went from motel to motel and was denied a room at every single one. Finally, he broke down and told one couple that he was a veteran, that he was a physician, that he meant no harm to anyone and just wanted to sleep. They still refused.

3. The story of a man who worked with the NAACP, was locked up in a mental institution, and then escaped with the help of a coordinated effort that had him in a coffin and traveling across state lines in different hearses.

4. The store clerk who owned a dog and taught that dog many tricks. One trick was for the clerk to ask the dog if he'd rather be black or dead. The dog was trained to respond by rolling over and playing dead.

There were many more stories about oppression and resistance, the times people bowed to authority and the times they defied it. The many ways that people faced indignities and swallowed the insults, turned the other cheek, and then came back to fight another round. The consequences of leaving behind family and friends to start a new life. The consequences of working long, hard hours to make a better life for a family that you rarely get to see. The consequences of moving from the rural south to the industrial north.

I don't think I've done a good job of describing why this book is so moving. But it's a huge book, and it covers so much! It's hard to cover all of that in one post. All I can say is that it is an excellent story of how much progress we've made and the cost of that progress, not only for the country as a whole but for so many individual people. And it serves as an important reminder that individual decisions matter and can make a difference in the world.

Friday, January 6, 2017

Intisar Khanani's Memories of Ash

I was lucky enough to get an early copy of Intisar Khanani's Memories of Ash back in May when it was first released. I really love Khanani's work, and I fully intended to sit down and read the book as soon as I received it. But things do not often work out as well as you wish, and I never got around to reading this book until over the Christmas long weekend. This ended up working out for the best, though, as I had precious hours in a row to devote to reading and became fully enmeshed in the story.

Memories of Ash picks up about a year after Sunbolt ends. It's been well over two years since I read Sunbolt and I admit that I was foggy on some of the details (and, er, major plot points). I highly recommend that you read Sunbolt before you read Memories of Ash, and if you are the type to re-read when a new book in a series comes out, I recommend you do that, too. I rarely do that and rely solely on memory and chutzpah to get me through, and usually it works fairly well.

Anyway, Memories of Ash begins with Hitomi living a quiet, peaceful life in the country with an older mage, Brigit Stormwind, who is teaching her how to hone her magical skills. But soon people come for Stormwind, accusing her of treason and other trumped-up charges. Stormwind is taken away; Hitomi leaves soon after to go and save her. The rest of the book follows Hitomi as she sets out to accomplish this very difficult task.

One of the greatest things about Khanani as an author, at least to me, is that she rewards her characters for being good people. So often in fiction, people are shown to be unkind or vindictive or two-faced or untrustworthy. In Khanani's books, people are shown to be kind and supportive. They may have different priorities or goals, but they listen to each other and attempt to understand motives. At a time when it feels like people just talk past each other and don't really listen and are not willing to hear anything they don't want to hear, I cannot express how much I treasure this aspect of Khanani's work.

We learn more about Hitomi's past in this book, and while that knowledge adds intriguing depth and great promise to this series, Hitomi herself remains loyal, steadfast and honorable in light of everything she finds out. She's a pretty great lead character, so it's no surprise that she makes some really wonderful friends.

In reading this book, I also understood why Khanani spent so much time writing and editing it. Not only has she constructed a beautifully intricate world and peopled it with a diverse and fascinating cast, but she's also given all of them rich cultural backgrounds and hinted at more to come. There are a lot of politics at play here and Hitomi has to navigate all of that in addition to trying to meet her own goals. She has so much empathy for people, and because of that, she really tries to understand what motivates them and what would make them believe her and help her. If this sounds like manipulation, then I am not describing it well. Hitomi does not pray on people's fears or weaknesses, she looks for common ground.

And this is one of the reasons I love some types of fantasy and really hate others. I prefer the premise that people are good and can see some of themselves in others, that power is a privilege that should be wielded fairly and with integrity. I don't like fantasy that implies that as soon as someone gets power, that person becomes corrupt and savors violence or cruelty (especially towards women). I appreciate that Khanani seems to have that same vision; most of her characters are kind and strong and stand up for what's right, even the ones with smaller roles. And that means a lot. So even if it takes another two years for the next installment in this series to come out, I'll count it worth the wait if it continues this excellent trend.

Memories of Ash picks up about a year after Sunbolt ends. It's been well over two years since I read Sunbolt and I admit that I was foggy on some of the details (and, er, major plot points). I highly recommend that you read Sunbolt before you read Memories of Ash, and if you are the type to re-read when a new book in a series comes out, I recommend you do that, too. I rarely do that and rely solely on memory and chutzpah to get me through, and usually it works fairly well.

Anyway, Memories of Ash begins with Hitomi living a quiet, peaceful life in the country with an older mage, Brigit Stormwind, who is teaching her how to hone her magical skills. But soon people come for Stormwind, accusing her of treason and other trumped-up charges. Stormwind is taken away; Hitomi leaves soon after to go and save her. The rest of the book follows Hitomi as she sets out to accomplish this very difficult task.