There are a few times in her book Testosterone Rex in which Cordelia Fine self-deprecatingly talks about how, when she introduces herself to people, she is always saddened by the fact that she is not immediately surrounded by fangirls and fanboys who carry copies of her book around and want her to autograph it right then and there.

I admit that I don't carry Fine's Delusions of Gender around with me, but I am a HUGE fan of the book, and I'm pretty sure that if I were ever to meet Fine in person, I would be a total fangirl and absolutely ask to take a photo with her and all sorts of other things.

SO NOW YOU KNOW, CORDELIA - you are just meeting the wrong people. You have LOADS of fans who love you and your work.

I was pretty excited to learn that Fine had a new book out, this one about how people assume that testosterone is a hormone that creates vast differences between men and women (besides the private bits), and that it can explain a lot of things about human and animal behavior, from risk-taking to spreading the seed to being successful at work. And, as she does, Fine shoots all of these assumptions down using science.

The book clocks in at less than 200 pages before the footnotes, so it's not long, but there's a LOT packed into its pages. I don't remember this happening at all while I read Delusions of Gender, but I admit that reading all these details about the sex habits of fish and insects was a little trying for me. I didn't love every page of this book the way I loved every page of Delusions of Gender, but I do think the pay-off for this book is really just as good! Just know that I skimmed some parts of it.

Fine makes a lot of great points, and some of them really resonated with me. For example, she talks about risk-taking and how studies have shown that men are more likely to take risks than women are. Then she totally breaks apart this whole thing, and it was amazing. FIRST, she says that when you separate people by ethnicity, it is actually mostly just white men who feel the world is super-safe and therefore are quite willing to take risks. And, within that subset, it was white men who were "well educated, rich, and politically conservative, as well as more trusting of institutions and authorities, and opposed to a "power to the people" view of the world..."

Who would have thought? The people with the most privilege are the ones most likely to take "risks," possibly because they are the least likely to lose.

Fine goes on to state that people view risks very differently, and someone may consider one thing quite risky and something else quite safe. For example, a skydiver could be very conservative with his money, and a Wall Street speculator could drive a Volvo. It's the individual's perception of the risk that is important, not a general idea of what is risky and what is not.

A salient point to bring those two facts together? "When asked about the risks to human health, safety, or prosperity arising from high tax rates for business, now it was the women's and minority men's turn to be sanguine." (Ah, so rich white men were very worried about the risks that would come with taxing business, whereas the people who would more likely benefit from taking that risk were not so worried!) Basically, people of both genders and all races take risks all the time, it is just that we seem to value some actions as being more risky (skydiving) than others (accepting a job at a company where that you will be the only woman, surrounded by bros).

Cordelia Fine is one of those people with so much glorious righteous anger PLUS a fantastic sense of humor that you kind of want her to fight all your battles for you. She shares a story about how she went to a school sale and some woman was selling plastic knives, and made a point to say the girl could have a pink knife, but her brother could have red or blue. She talks about how early kids become aware of gender and what they are "supposed" to do. (She goes into even more detail on this in Delusions of Gender). She reminds us that we should never say stupid phrases like, "Boys will be boys," as though we should give them a free pass for being jerks. She really carries the banner on gender equality, and I love her for it.

Really excellent book! Go read it!

Showing posts with label women. Show all posts

Showing posts with label women. Show all posts

Thursday, June 8, 2017

Monday, April 17, 2017

Whatever happened to interracial love?

I heard about Kathleen Collins and her collection of short stories, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, in the New York Times Book Review, where I get many of my reading recommendations (and which has gotten better at reviewing books by people who are not white and male). Kathleen Collins was active in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, but most of her artistic work (films, plays, short stories) was produced in the 1980s. Her short stories were, for the most part, never published. Her daughter discovered them in a trunk.

It's always hard to judge artistic talent by stories left unpublished in a trunk, mainly because it's hard to know if these stories were complete or if the author still wanted to work on them. But the romance of the whole situation is just too much to pass up! Undiscovered author! A trunk! The perfect cultural moment! Stories on race, gender, sexuality! It's a lot of awesomeness. If it could happen for Emily Dickinson, can't it happen for other people, too?

I think it can, sometimes. But sometimes the collection can also be pretty inconsistent. I think that's true for Kathleen Collins. There is so much wit in her stories, so much that speaks to how fascinating and vibrant she must have been, how much fun she must have been to talk to. But there are other stories that feel unrefined or directionless. Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is more a collection of what was great potential, lost too early (Collins died of cancer in 1988 at age 46).

The stories are mainly pretty short, and race is alluded to in almost all of them. One story is told from the point of view of a man describing the perfect family, a close-knit unit that was beautiful, intelligent, and got along well. But then cracks start to show, and it turns out the family's future is not nearly as happy as one would hope. In another, a woman loyally sends letters and gifts to her husband in prison. When he gets out and moves to a foreign country (without her), she finds peace in a small, rural home and some new friends. In "The Uncle," the narrator relates the story of his uncle, who is ill and whom many describe as lazy for his whole life. But the narrator, upon reflection, thinks that his uncle was a hero, just for surviving..

It's always hard to judge artistic talent by stories left unpublished in a trunk, mainly because it's hard to know if these stories were complete or if the author still wanted to work on them. But the romance of the whole situation is just too much to pass up! Undiscovered author! A trunk! The perfect cultural moment! Stories on race, gender, sexuality! It's a lot of awesomeness. If it could happen for Emily Dickinson, can't it happen for other people, too?

I think it can, sometimes. But sometimes the collection can also be pretty inconsistent. I think that's true for Kathleen Collins. There is so much wit in her stories, so much that speaks to how fascinating and vibrant she must have been, how much fun she must have been to talk to. But there are other stories that feel unrefined or directionless. Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is more a collection of what was great potential, lost too early (Collins died of cancer in 1988 at age 46).

The stories are mainly pretty short, and race is alluded to in almost all of them. One story is told from the point of view of a man describing the perfect family, a close-knit unit that was beautiful, intelligent, and got along well. But then cracks start to show, and it turns out the family's future is not nearly as happy as one would hope. In another, a woman loyally sends letters and gifts to her husband in prison. When he gets out and moves to a foreign country (without her), she finds peace in a small, rural home and some new friends. In "The Uncle," the narrator relates the story of his uncle, who is ill and whom many describe as lazy for his whole life. But the narrator, upon reflection, thinks that his uncle was a hero, just for surviving..

But his weeping, wailing, and gnashing of teeth brimmed potent to overflowing in the room, and I began to weep for him, weep tears of pride and joy that he should have so soaked his life in sorrow and gone back to some ancient ritual beyond the blunt humiliation of his skin, with its bound-and-sealed possibilities; so refused to overcome his sorrow as some affliction to be transcended, some stumbling block put in his way for the sake of trial and endurance; so refused to strike out against it, go down in a blaze of responsibilities met and struggled with. No. He utterly honored his sorrow, gave in to it with such deep and boundless weeping that it seemed as I stood there he was the bravest man I had ever known.There was silver and gold in all the stories collected here, even if all of them didn't stick with me. So much about how difficult life can be when people expect so little of you, or treat you like you are less than what you know yourself to be. So much about the struggle to understand your parents or your children, about competing priorities for different generations and what they decide is worth fighting for. It's a lovely collection and well worth seeking out. Not only because it's amazing to discover the unknown work of a feminist civil rights cultural icon, but because the stories are quite good, too.

Wednesday, April 5, 2017

Women Culture and Politics

Women Culture and Politics is the first Angela Y Davis book I've ever read. For those of you who may not know, Angela Davis is a hugely influential feminist communist activist. She was very active in the 1960s with the Civil Rights movement, fought hard against Ronald Reagan when he was governor of California and when he was president, and continues to serve as a voice of resistance and strength.

Women Culture and Politics is a collection of Davis' essays and speeches from the 1980s and 1990s. I am not sure if it is the best book to start with, but I think this is mostly due to the format. I admit that my grasp of history from the 1980s and 1990s is not quite as extensive as I would like, and Davis' essays are very much commentary on the times. I wish that there was an introduction to the collection as a whole or to each specific essay so that I had a better grasp and understanding of the context in which she was writing the essay or delivering the speech. That would have helped me a lot to fully understand Davis' points.

[Side note: That said, I really need to learn more about the entire Reagan presidency. Does anyone have a book they recommend for that? I feel like Reagan comes up a LOT these days, and I would like to understand more of our history with Russia and Latin America and all the rest. So, please let me know if there is any book you think would be a good one to get some background!]

While some of the context of Davis' points was lost on me, a concerning number of points were still very relevant. I suppose in the grand scheme of things, 30 years is not so long a time in which to make real change in society. But it still feels depressing.

One thing Davis talked about in her essays comes up a lot in liberal discussion these days. And that is identity politics. I have been very up and down on identity politics and the impact of identity politics on our election and on the way people describe themselves now. I 100% believe that people should feel comfortable being their truest, best selves, and that they should feel safe enough to be open about who they are. But I also can feel exhausted by the number of identifiers everyone feels the need to use these days. And I am very concerned by the way identity politics has led to white nationalism and supremacy. Davis' approach to this is that everyone should come together.

There is a LOT in this book that is amazing. I folded so many pages down to note down quotes. It would be too much for me to share them all with you, so I recommend that instead, you just read the book and feel all the feels and become a Davis fangirl. I plan to read much more by her, and I look forward to the way she will challenge my thinking.

Women Culture and Politics is a collection of Davis' essays and speeches from the 1980s and 1990s. I am not sure if it is the best book to start with, but I think this is mostly due to the format. I admit that my grasp of history from the 1980s and 1990s is not quite as extensive as I would like, and Davis' essays are very much commentary on the times. I wish that there was an introduction to the collection as a whole or to each specific essay so that I had a better grasp and understanding of the context in which she was writing the essay or delivering the speech. That would have helped me a lot to fully understand Davis' points.

[Side note: That said, I really need to learn more about the entire Reagan presidency. Does anyone have a book they recommend for that? I feel like Reagan comes up a LOT these days, and I would like to understand more of our history with Russia and Latin America and all the rest. So, please let me know if there is any book you think would be a good one to get some background!]

While some of the context of Davis' points was lost on me, a concerning number of points were still very relevant. I suppose in the grand scheme of things, 30 years is not so long a time in which to make real change in society. But it still feels depressing.

One thing Davis talked about in her essays comes up a lot in liberal discussion these days. And that is identity politics. I have been very up and down on identity politics and the impact of identity politics on our election and on the way people describe themselves now. I 100% believe that people should feel comfortable being their truest, best selves, and that they should feel safe enough to be open about who they are. But I also can feel exhausted by the number of identifiers everyone feels the need to use these days. And I am very concerned by the way identity politics has led to white nationalism and supremacy. Davis' approach to this is that everyone should come together.

"...we must begin to merge that double legacy in order to create a single continuum, one that solidly represents the aspirations of all women in our society. We must begin to create a revolutionary, multiracial women's movement that seriously addresses the main issues affecting poor and working-class women."This comes up again and again in Davis' writing, this idea that rich, white women seem to fight a completely different battle than working class women of color, and that they often forget to fight for the rights of people who are not as well off as they are. This is still relevant today, and it came up a lot with the Women's March on Washington and it continues to come up with women's rights now when we talk about Planned Parenthood (which we seem to talk about all the time). It continues now as people obsess over the rural white vote. I feel like there must be a way to talk about the issues in ways that are less divisive but that doesn't make people feel left behind. But do we all just jump too quickly now to take offense, to say, "What about me? You mentioned everyone's suffering but mine!" And instead of giving a person the opportunity to go back and consider and grow, we assume the worst and shame the person and then the person gets so nervous about saying anything wrong, but doesn't actually change his/her inner thoughts. Just hides them. And then we are where we are.

There is a LOT in this book that is amazing. I folded so many pages down to note down quotes. It would be too much for me to share them all with you, so I recommend that instead, you just read the book and feel all the feels and become a Davis fangirl. I plan to read much more by her, and I look forward to the way she will challenge my thinking.

Monday, February 27, 2017

The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe

I read Kij Johnson's The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe with my feminist science fiction book club, and it's the first book I've read that made me really love being in a book club. I'm not very good at book clubs because I don't like reading books because I have to read them. But feminist science fiction is a pretty great space, so it's not hard to get excited about reading for each meeting. Also, the women in the club are so cool.

Anyway, onto the book! I really enjoyed The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe when I read it, but it was only after our book club meeting that I realized on just how many levels it is fantastically feminist. For such a slim volume (about 165 pages), it really packs a punch. Especially when you compare it to its inspiration, HP Lovecraft's The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, which I tried to read prior to reading this one, and just could NOT get through.

If I had read the entirety of Lovecraft's book, I probably would have even more thoroughly appreciated Johnson's version of it. But I would say I read enough of Lovecraft to know that I didn't want to read any more. Where Lovecraft seems to have no real focus except in introducing as many bizarre characters and species as possible, Johnson gives readers a more internal focus on Vellitt Boe herself. While she is not particularly introspective, we learn enough about her to want to know even more about her.

Vellitt Boe is a professor at a women's college in a dream-world. One of her students has run away with someone from "the real world," and Vellitt must go bring her student back. She embarks (with zero drama) on this quest on her own, knowing that it could take a very long time and will probably be super-dangerous. But Vellitt is someone who does what's right, and so she hops to it.

This is a short book, so I don't want to give a lot away on the plot points. But a few things were really great and came up in our book club and really made me appreciate the story even more:

1. Vellitt is middle-aged. She's a middle-aged adventure heroine! You do not find those around very often at all, and I just love that making Vellitt middle-aged and female is in itself a completely feminist way of setting up this story. She is aware that she used to be super-attractive and that she used her charms to get her way and that, being female, her attractiveness lessens with age. But she doesn't really miss her past, she is happy with who she is. There's also this whole interplay with a former lover who does not look like he's aged at all, and the way they look at each other and how Vellitt reflects upon him and their past relationship is just brilliant.

2. Vellitt is "ethnic." Ok, ok, I admit I TOTALLY did not catch this when I was reading the book. Ironically, the two POC in the book club defaulted to thinking Vellitt was white, whereas everyone in the book club who was white was really quick to catch onto the fact that Vellitt had skin "the color of mud" and hair she wore in braids. Oops. I don't think the race component in this book is as strong as it could have been, considering the author pointed out at the end that she wrote it partially to counteract the racism in Lovecraft's book. I feel like if I missed it, it was pretty subtle, but maybe I am just not as attentive a reader as I thought. ALSO, I would say that, based on that description, the cover of this book feels a little white-washed. Maybe that is gray hair, but it's definitely not in braids.

3. The girl who ran away from school is amazing. She doesn't play a huge part, and, seeing as she's a beautiful college student who ran away with a boy, you'd think she'd be pretty flighty and lame. But she is not. She's strong and straight-forward and everything that is great.

4. The setting. Vellitt Boe's world is capricious and mercurial and does not obey the laws of physics. We don't get a ton of detail about the world because, well, the book is 165 pages long. But what we do get is fascinating. For example, the sky is never the same color, it seems to roil and boil all the time. There are exactly 79 stars in the sky. There are gods, and the gods are not very nice. While trying to make my way through Lovecraft's book, I felt like he just kept going ON AND ON with no point at all. While reading Johnson's book, I felt none of that. I am not sure why because really, many of the plot points are the same and Vellitt goes on essentially the same journey as was laid out previously. But I think a lot of it has to do with the way Johnson describes the setting and gives us a little background on the characters that Vellitt encounters.

So, this book! It's great! It's not even very long but so great! I am not sure if it is a great first foray into fantasy and science fiction as it is very dream-like and many characters that show up seem to disappear and then not matter at all to the plot. But if you are ok with that and want to read something that is awesomely feminist but subtly so, then I highly recommend it. And it won't take too long to read, either :-)

Anyway, onto the book! I really enjoyed The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe when I read it, but it was only after our book club meeting that I realized on just how many levels it is fantastically feminist. For such a slim volume (about 165 pages), it really packs a punch. Especially when you compare it to its inspiration, HP Lovecraft's The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, which I tried to read prior to reading this one, and just could NOT get through.

If I had read the entirety of Lovecraft's book, I probably would have even more thoroughly appreciated Johnson's version of it. But I would say I read enough of Lovecraft to know that I didn't want to read any more. Where Lovecraft seems to have no real focus except in introducing as many bizarre characters and species as possible, Johnson gives readers a more internal focus on Vellitt Boe herself. While she is not particularly introspective, we learn enough about her to want to know even more about her.

Vellitt Boe is a professor at a women's college in a dream-world. One of her students has run away with someone from "the real world," and Vellitt must go bring her student back. She embarks (with zero drama) on this quest on her own, knowing that it could take a very long time and will probably be super-dangerous. But Vellitt is someone who does what's right, and so she hops to it.

This is a short book, so I don't want to give a lot away on the plot points. But a few things were really great and came up in our book club and really made me appreciate the story even more:

1. Vellitt is middle-aged. She's a middle-aged adventure heroine! You do not find those around very often at all, and I just love that making Vellitt middle-aged and female is in itself a completely feminist way of setting up this story. She is aware that she used to be super-attractive and that she used her charms to get her way and that, being female, her attractiveness lessens with age. But she doesn't really miss her past, she is happy with who she is. There's also this whole interplay with a former lover who does not look like he's aged at all, and the way they look at each other and how Vellitt reflects upon him and their past relationship is just brilliant.

2. Vellitt is "ethnic." Ok, ok, I admit I TOTALLY did not catch this when I was reading the book. Ironically, the two POC in the book club defaulted to thinking Vellitt was white, whereas everyone in the book club who was white was really quick to catch onto the fact that Vellitt had skin "the color of mud" and hair she wore in braids. Oops. I don't think the race component in this book is as strong as it could have been, considering the author pointed out at the end that she wrote it partially to counteract the racism in Lovecraft's book. I feel like if I missed it, it was pretty subtle, but maybe I am just not as attentive a reader as I thought. ALSO, I would say that, based on that description, the cover of this book feels a little white-washed. Maybe that is gray hair, but it's definitely not in braids.

3. The girl who ran away from school is amazing. She doesn't play a huge part, and, seeing as she's a beautiful college student who ran away with a boy, you'd think she'd be pretty flighty and lame. But she is not. She's strong and straight-forward and everything that is great.

4. The setting. Vellitt Boe's world is capricious and mercurial and does not obey the laws of physics. We don't get a ton of detail about the world because, well, the book is 165 pages long. But what we do get is fascinating. For example, the sky is never the same color, it seems to roil and boil all the time. There are exactly 79 stars in the sky. There are gods, and the gods are not very nice. While trying to make my way through Lovecraft's book, I felt like he just kept going ON AND ON with no point at all. While reading Johnson's book, I felt none of that. I am not sure why because really, many of the plot points are the same and Vellitt goes on essentially the same journey as was laid out previously. But I think a lot of it has to do with the way Johnson describes the setting and gives us a little background on the characters that Vellitt encounters.

So, this book! It's great! It's not even very long but so great! I am not sure if it is a great first foray into fantasy and science fiction as it is very dream-like and many characters that show up seem to disappear and then not matter at all to the plot. But if you are ok with that and want to read something that is awesomely feminist but subtly so, then I highly recommend it. And it won't take too long to read, either :-)

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

The One Hundred Nights of Hero, by Isabel Greenberg

I adored Isabel Greenberg's The Encyclopedia of Early Earth, so as soon as I heard about her new book The One Hundred Nights of Hero, I put it on hold at the library. And this book was just what I needed. It's all about women being amazing, about the power of stories, about the importance of resisting, even in the face of inevitable failure, and so much more.

I debated whether I should review this book or not because it's one of those books that I just really loved because it was kind and beautiful. However, The One Hundred Nights of Hero tackles some really big topics in a gloriously feminist way. While The Encyclopedia of Early Earth was complex in its layering of stories within stories, the stories themselves were not super complicated (that I remember) and the story was centered on a man seeking love. The One Hundred Nights of Hero is centered on two women in love. Cherry is married to an imbecile who challenges his friend to seduce her in 100 nights. His friend agrees, and is pretty clear that if seduction doesn't work, force will. Cherry and her love, Hero, come up with a plan to distract the nefarious villain with stories each night. But not just any stories, stories about women and the power of knowledge and the importance of choice.

In none of these stories is there a happy ending of "Girl meets boy, girl marries boy, they live happily ever after." There are stories of love and how beautiful a thing it can be, but Greenberg always stresses that the ability of a woman to choose her fate is equally, if not more, important. Some of the stories end happily because women find ways to live independently. Many of them end sadly because the women featured in them do not fit neatly into the strict definitions that patriarchal societies have set for them.

That makes it sound as though this is a melancholy and depressing book, but it is not that at all. It's absolutely amazing. There is so much humor, so much kindness and friendship and loyalty, and glorious sisterhood. Also, the illustrations are beautiful. And then, of course, there are the stories.

It's an excellent, gorgeous book, and I intend to splurge and buy some Isabel Greenberg for myself for my birthday this year - she's absolutely worth having on your keeper shelf.

I debated whether I should review this book or not because it's one of those books that I just really loved because it was kind and beautiful. However, The One Hundred Nights of Hero tackles some really big topics in a gloriously feminist way. While The Encyclopedia of Early Earth was complex in its layering of stories within stories, the stories themselves were not super complicated (that I remember) and the story was centered on a man seeking love. The One Hundred Nights of Hero is centered on two women in love. Cherry is married to an imbecile who challenges his friend to seduce her in 100 nights. His friend agrees, and is pretty clear that if seduction doesn't work, force will. Cherry and her love, Hero, come up with a plan to distract the nefarious villain with stories each night. But not just any stories, stories about women and the power of knowledge and the importance of choice.

In none of these stories is there a happy ending of "Girl meets boy, girl marries boy, they live happily ever after." There are stories of love and how beautiful a thing it can be, but Greenberg always stresses that the ability of a woman to choose her fate is equally, if not more, important. Some of the stories end happily because women find ways to live independently. Many of them end sadly because the women featured in them do not fit neatly into the strict definitions that patriarchal societies have set for them.

That makes it sound as though this is a melancholy and depressing book, but it is not that at all. It's absolutely amazing. There is so much humor, so much kindness and friendship and loyalty, and glorious sisterhood. Also, the illustrations are beautiful. And then, of course, there are the stories.

It's an excellent, gorgeous book, and I intend to splurge and buy some Isabel Greenberg for myself for my birthday this year - she's absolutely worth having on your keeper shelf.

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

Review-itas: Books that confused me

Guys, Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee confused me so much that I cannot even explain the cover of this book to you. Does it fit with the story? I don't know. I mean, the story takes place in space, so that part is accurate. But what is the spiky thing that dominates the image? I don't know.

As far as I can tell, Ninefox Gambit is set in a civilization that really likes order. There appears to be a massive mathematical algorithm (the "calendar") that oversees every tiny thing, especially in the military. Possibly people exist outside of the military, but it is hard to tell. There is also a very rigid caste system in place, with different groups of people going into different areas of study and conforming to very specific traits. The main character, Cheris, is in the military leading her team and somehow goes against the calendar. This means she's in trouble and she's given a very big, basically impossible task to go kill some heretics, for which she asks for help from this undead ghost who won every battle he ever fought, except he also turned traitor and got an obscene number of people killed.

There was a lot in this book that I did not understand. This book is like all my fears and feelings of intimidation about science fiction coming to fruition. Once I got to the end and things started moving a little faster and became more people-focused than calendar-focused (I still cannot grasp this calendar system, and it DRIVES ME CRAZY), I got more into it. And it certainly ends on a high note that bodes well for the series to follow. So I eventually got the high-level plot, but I could tell you nothing about the setting.

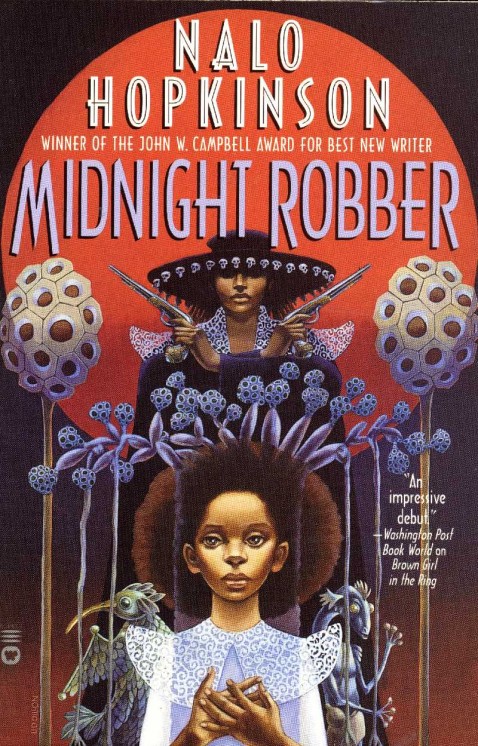

After my appalling showing in 2016 of reading only four books off my TBR list, I was determined to do better in 2017. (To be fair, I set a pretty low bar for myself, so I feel confident I can beat it.) I read and enjoyed Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber, so I decided to give Sister Mine a go. Many of the same elements that I loved in Midnight Robber are present here - a strong cultural identity, humor, and fantastic female characters at the center. Sister Mine is often compared to American Gods or Anansi Gods because it is about a family of demigods. But whereas Neil Gaiman's book is almost entirely about men, Hopkinson's puts women very much at the center of the story. She plays with gender, sexuality, and many other themes while she wreaks havoc with the lives of both humans and gods.

I listened to Sister Mine on audio, and the narrator is excellent. I don't listen to many audiobooks any more, but I was pretty much instantly drawn into this one. I enjoyed many things about this story, but parts of it were just a bit too out there for me, particularly towards the end when things became very convoluted to me. I really liked many of the characters in this book, but with about two hours to go, I was just ready for the book to end. There were plot points that came up that didn't make a ton of sense to me or fit into the rest of the story, and then there was this whole section at the end that I was just... I don't know what was happening. I feel like maybe if I were reading a physical copy of the book instead of listening to an audiobook, it would have been easier for me to understand what was happening. Or maybe I'm just so confused by the real world that fantastical and science fiction worlds go too far for me. Regardless, this was a lighter book than Midnight Robber for sure, with humor and pretty great family dynamics. So if you want to give Hopkinson a try but don't want all the heavy stuff, this could be a good one to start with. But I wouldn't say it's as strong as Midnight Robber.

As far as I can tell, Ninefox Gambit is set in a civilization that really likes order. There appears to be a massive mathematical algorithm (the "calendar") that oversees every tiny thing, especially in the military. Possibly people exist outside of the military, but it is hard to tell. There is also a very rigid caste system in place, with different groups of people going into different areas of study and conforming to very specific traits. The main character, Cheris, is in the military leading her team and somehow goes against the calendar. This means she's in trouble and she's given a very big, basically impossible task to go kill some heretics, for which she asks for help from this undead ghost who won every battle he ever fought, except he also turned traitor and got an obscene number of people killed.

There was a lot in this book that I did not understand. This book is like all my fears and feelings of intimidation about science fiction coming to fruition. Once I got to the end and things started moving a little faster and became more people-focused than calendar-focused (I still cannot grasp this calendar system, and it DRIVES ME CRAZY), I got more into it. And it certainly ends on a high note that bodes well for the series to follow. So I eventually got the high-level plot, but I could tell you nothing about the setting.

After my appalling showing in 2016 of reading only four books off my TBR list, I was determined to do better in 2017. (To be fair, I set a pretty low bar for myself, so I feel confident I can beat it.) I read and enjoyed Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber, so I decided to give Sister Mine a go. Many of the same elements that I loved in Midnight Robber are present here - a strong cultural identity, humor, and fantastic female characters at the center. Sister Mine is often compared to American Gods or Anansi Gods because it is about a family of demigods. But whereas Neil Gaiman's book is almost entirely about men, Hopkinson's puts women very much at the center of the story. She plays with gender, sexuality, and many other themes while she wreaks havoc with the lives of both humans and gods.

I listened to Sister Mine on audio, and the narrator is excellent. I don't listen to many audiobooks any more, but I was pretty much instantly drawn into this one. I enjoyed many things about this story, but parts of it were just a bit too out there for me, particularly towards the end when things became very convoluted to me. I really liked many of the characters in this book, but with about two hours to go, I was just ready for the book to end. There were plot points that came up that didn't make a ton of sense to me or fit into the rest of the story, and then there was this whole section at the end that I was just... I don't know what was happening. I feel like maybe if I were reading a physical copy of the book instead of listening to an audiobook, it would have been easier for me to understand what was happening. Or maybe I'm just so confused by the real world that fantastical and science fiction worlds go too far for me. Regardless, this was a lighter book than Midnight Robber for sure, with humor and pretty great family dynamics. So if you want to give Hopkinson a try but don't want all the heavy stuff, this could be a good one to start with. But I wouldn't say it's as strong as Midnight Robber.

Friday, January 6, 2017

Intisar Khanani's Memories of Ash

I was lucky enough to get an early copy of Intisar Khanani's Memories of Ash back in May when it was first released. I really love Khanani's work, and I fully intended to sit down and read the book as soon as I received it. But things do not often work out as well as you wish, and I never got around to reading this book until over the Christmas long weekend. This ended up working out for the best, though, as I had precious hours in a row to devote to reading and became fully enmeshed in the story.

Memories of Ash picks up about a year after Sunbolt ends. It's been well over two years since I read Sunbolt and I admit that I was foggy on some of the details (and, er, major plot points). I highly recommend that you read Sunbolt before you read Memories of Ash, and if you are the type to re-read when a new book in a series comes out, I recommend you do that, too. I rarely do that and rely solely on memory and chutzpah to get me through, and usually it works fairly well.

Anyway, Memories of Ash begins with Hitomi living a quiet, peaceful life in the country with an older mage, Brigit Stormwind, who is teaching her how to hone her magical skills. But soon people come for Stormwind, accusing her of treason and other trumped-up charges. Stormwind is taken away; Hitomi leaves soon after to go and save her. The rest of the book follows Hitomi as she sets out to accomplish this very difficult task.

One of the greatest things about Khanani as an author, at least to me, is that she rewards her characters for being good people. So often in fiction, people are shown to be unkind or vindictive or two-faced or untrustworthy. In Khanani's books, people are shown to be kind and supportive. They may have different priorities or goals, but they listen to each other and attempt to understand motives. At a time when it feels like people just talk past each other and don't really listen and are not willing to hear anything they don't want to hear, I cannot express how much I treasure this aspect of Khanani's work.

We learn more about Hitomi's past in this book, and while that knowledge adds intriguing depth and great promise to this series, Hitomi herself remains loyal, steadfast and honorable in light of everything she finds out. She's a pretty great lead character, so it's no surprise that she makes some really wonderful friends.

In reading this book, I also understood why Khanani spent so much time writing and editing it. Not only has she constructed a beautifully intricate world and peopled it with a diverse and fascinating cast, but she's also given all of them rich cultural backgrounds and hinted at more to come. There are a lot of politics at play here and Hitomi has to navigate all of that in addition to trying to meet her own goals. She has so much empathy for people, and because of that, she really tries to understand what motivates them and what would make them believe her and help her. If this sounds like manipulation, then I am not describing it well. Hitomi does not pray on people's fears or weaknesses, she looks for common ground.

And this is one of the reasons I love some types of fantasy and really hate others. I prefer the premise that people are good and can see some of themselves in others, that power is a privilege that should be wielded fairly and with integrity. I don't like fantasy that implies that as soon as someone gets power, that person becomes corrupt and savors violence or cruelty (especially towards women). I appreciate that Khanani seems to have that same vision; most of her characters are kind and strong and stand up for what's right, even the ones with smaller roles. And that means a lot. So even if it takes another two years for the next installment in this series to come out, I'll count it worth the wait if it continues this excellent trend.

Memories of Ash picks up about a year after Sunbolt ends. It's been well over two years since I read Sunbolt and I admit that I was foggy on some of the details (and, er, major plot points). I highly recommend that you read Sunbolt before you read Memories of Ash, and if you are the type to re-read when a new book in a series comes out, I recommend you do that, too. I rarely do that and rely solely on memory and chutzpah to get me through, and usually it works fairly well.

Anyway, Memories of Ash begins with Hitomi living a quiet, peaceful life in the country with an older mage, Brigit Stormwind, who is teaching her how to hone her magical skills. But soon people come for Stormwind, accusing her of treason and other trumped-up charges. Stormwind is taken away; Hitomi leaves soon after to go and save her. The rest of the book follows Hitomi as she sets out to accomplish this very difficult task.

One of the greatest things about Khanani as an author, at least to me, is that she rewards her characters for being good people. So often in fiction, people are shown to be unkind or vindictive or two-faced or untrustworthy. In Khanani's books, people are shown to be kind and supportive. They may have different priorities or goals, but they listen to each other and attempt to understand motives. At a time when it feels like people just talk past each other and don't really listen and are not willing to hear anything they don't want to hear, I cannot express how much I treasure this aspect of Khanani's work.

We learn more about Hitomi's past in this book, and while that knowledge adds intriguing depth and great promise to this series, Hitomi herself remains loyal, steadfast and honorable in light of everything she finds out. She's a pretty great lead character, so it's no surprise that she makes some really wonderful friends.

In reading this book, I also understood why Khanani spent so much time writing and editing it. Not only has she constructed a beautifully intricate world and peopled it with a diverse and fascinating cast, but she's also given all of them rich cultural backgrounds and hinted at more to come. There are a lot of politics at play here and Hitomi has to navigate all of that in addition to trying to meet her own goals. She has so much empathy for people, and because of that, she really tries to understand what motivates them and what would make them believe her and help her. If this sounds like manipulation, then I am not describing it well. Hitomi does not pray on people's fears or weaknesses, she looks for common ground.

And this is one of the reasons I love some types of fantasy and really hate others. I prefer the premise that people are good and can see some of themselves in others, that power is a privilege that should be wielded fairly and with integrity. I don't like fantasy that implies that as soon as someone gets power, that person becomes corrupt and savors violence or cruelty (especially towards women). I appreciate that Khanani seems to have that same vision; most of her characters are kind and strong and stand up for what's right, even the ones with smaller roles. And that means a lot. So even if it takes another two years for the next installment in this series to come out, I'll count it worth the wait if it continues this excellent trend.

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Hope Jahren's Lab Girl

One of the things I most missed about blogging while I was in and out this year was discussing books with you guys. Thus, one of the first things I did when I came back to blogging was to plan a buddy read with one of my favoritest and longest-lasting blogging friends, Ana of things mean a lot. We chose to read Hope Jahren's memoir Lab Girl because reading about women rocking the science world seemed like a really nice thing to do after the horrors (that continue) of Brexit and the American Presidential election.

Lab Girl is written by a plant biologist who does research on topics that seem to be quite fascinating (at least at the macro level. At the micro level, it seems like a lot of sorting through dirt). She writes about how she got into biology, her life as a biologist, and her friendship with someone who is hugely important to her personal and professional life. Throughout the book, there are vignettes that describe the life of a tree, from seed to seedling to battling disease and other threats to communicating with other plants. Those vignettes are beautiful.

Unfortunately, Lab Girl wasn't quite what we were expecting, and neither of us loved it as much as we'd hoped. But there were some really great parts! Below is our discussion of the book, if you care to read it:

Lab Girl is written by a plant biologist who does research on topics that seem to be quite fascinating (at least at the macro level. At the micro level, it seems like a lot of sorting through dirt). She writes about how she got into biology, her life as a biologist, and her friendship with someone who is hugely important to her personal and professional life. Throughout the book, there are vignettes that describe the life of a tree, from seed to seedling to battling disease and other threats to communicating with other plants. Those vignettes are beautiful.

Unfortunately, Lab Girl wasn't quite what we were expecting, and neither of us loved it as much as we'd hoped. But there were some really great parts! Below is our discussion of the book, if you care to read it:

Labels:

biography,

contemporary,

non-fiction,

science,

women

Monday, December 5, 2016

All the Single Ladies

I first heard Rebecca Traister when she was interviewed on NPR. She spoke about her book, All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation. I have read (or tried to read) a few non-fiction books on women that just did not work for me - Bachelor Girl and Spinster being two of them. Traister sounded much more up my alley, and so I put her book on my radar.

I mostly read this book after the election this month. I thought it would be difficult and painful to do, but it was more like a balm. Throughout history, people have had to fight, tooth and nail, for their rights. And then they have to keep fighting to keep those rights. It's exhausting. It takes SO LONG to move forward even an inch, and then BAM! someone else comes into office and everything moves backwards again so quickly.

It's strange, admittedly, to describe knowing this as a "balm," but it kind of is. Every time a group fights for recognition and respect and rights, there is another group that feels threatened and fights tooth and nail against it. Often, the group that is threatened wins. Sadly, fear is a huge motivator.

Thus, when you look at civil rights movements throughout history, there is always this back and forth motion. This seems to be particularly true for women's rights, though it might just seem that way to me because I have read more about the women's movements than other ones. I suppose I have accepted that we are now in what appears to be a global backward motion on many civil rights. When I say that I have "accepted" this, I don't mean that I won't fight for those rights. What I mean is that I realize there are highs and lows, and I feel like this is our low. It's our time to fight so that we move even further when we get to the next high. Perhaps knowing that we are at the low and looking at history makes me realize that there are still highs to come.

Back to the book.

I listened to All the Single Ladies on audiobook, so I don't have a lot of quotes to share. That said, there were many quotes in this book, not only from history but from very modern times, about how dangerous and selfish and horrible single women are. This risk of women not reproducing to continue the species (or a very specific portion of the species) seems to threaten people at all levels and at all times and for all reasons.

What I really enjoyed about Traister's approach is that she looked at single women from many perspectives. She talks about how life for women in cities is different than life in suburban and rural areas, about female friendship, about women living on their own. She talks about why women choose to stay single (for work, money, independence, choice), not only rich women but also poor women. She talks about how people assume single women live hugely promiscuous lives when the reality is usually quite different, single moms, and the families that women create for themselves when they are not married.

Right at the start, Traister admits that she has an urban, educated, white slant to her book. That said, she does make some effort to meet and talk to people who have had different experiences. She also cites a lot of evidence about people from many walks of life.

I have been single my whole life, and I have many single female friends, and this book really resonated with me. Contrary to what many people think, I do not spend my nights desperately wishing there was a man in my life (though admittedly, there are some times, usually during engagement parties and weddings and showers, when I do). I also don't go out with dozens of guys a year. I'm not a shrew who is unkind to people (though I admit that I can be quite unkind to people I dislike strongly), and I'm not an anti-social, awkward person who stays at home every night with her books and wine (though I do enjoy evenings by myself just as much as I enjoy spending time with other people). I would be happy to find a guy that I really love and get married, but if I do not meet one, I am pretty sure I will be happy and fulfilled in my life. Except, of course, for everyone always wondering why I am single and what's wrong with me and when I'll finally stop being so picky.

Rebecca Traister understands all of this, and I felt so validated by this book. I think many people would. I love how Traister sets up historical "norms" as completely outside the norm. For example, so many people look back on women getting married young and then having children as being the basis of so much economic growth and prosperity. But even through history, many women have had to work outside the home to make ends meet. And people make it seem as though women are being selfish and thinking only of themselves and putting the world at great risk. But really, they're just making reasonable decisions for themselves, and people who complain about what they're doing should just get over themselves.

This book is not exhaustive by any means, but I don't think Traister is trying to be exhaustive. She shares anecdotes about herself and from her friends, she tells us about the choices women have made through history and now, and what some of the numbers behind the trends mean. I think this book would be a fantastic companion to Gail Collins' books about women in America and the long, winding path that the women's movement has taken. Those books (referenced below) give a bit more breadth to the history whereas Traister's book has a personal and more "everyday woman" feel.

I've been reading a ton of non-fiction lately! Sorry for all the heavy subject reviews. Though really, this book is not heavy by any means - it's a very informative read, and I am glad to add it to my list of books that are refreshing and kind to women who make choices in life that not everyone understands.

Want to dig deeper on this subject? Here are a few links:

Shorter reads -

"On Spinsters," by Briallen Hopper, which is a review of a different book but makes fantastic points

"We Just Can't Handle Diversity," by Lisa Burrell, about how we all have biases and should acknowledge them instead of pretending we are totally objective about stuff

Long reads -

America's Women and When Everything Changed, by Gail Collins; I love these books about the history of women's rights and empowerment in America

Delusions of Gender, by Cordelia Fine; also absolutely amazing

Have a listen -

The Lady Vanishes episode of the Revisionist History podcast

Watch -

"We Should All be Feminists" TEDx video by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

I mostly read this book after the election this month. I thought it would be difficult and painful to do, but it was more like a balm. Throughout history, people have had to fight, tooth and nail, for their rights. And then they have to keep fighting to keep those rights. It's exhausting. It takes SO LONG to move forward even an inch, and then BAM! someone else comes into office and everything moves backwards again so quickly.

It's strange, admittedly, to describe knowing this as a "balm," but it kind of is. Every time a group fights for recognition and respect and rights, there is another group that feels threatened and fights tooth and nail against it. Often, the group that is threatened wins. Sadly, fear is a huge motivator.

Thus, when you look at civil rights movements throughout history, there is always this back and forth motion. This seems to be particularly true for women's rights, though it might just seem that way to me because I have read more about the women's movements than other ones. I suppose I have accepted that we are now in what appears to be a global backward motion on many civil rights. When I say that I have "accepted" this, I don't mean that I won't fight for those rights. What I mean is that I realize there are highs and lows, and I feel like this is our low. It's our time to fight so that we move even further when we get to the next high. Perhaps knowing that we are at the low and looking at history makes me realize that there are still highs to come.

Back to the book.

I listened to All the Single Ladies on audiobook, so I don't have a lot of quotes to share. That said, there were many quotes in this book, not only from history but from very modern times, about how dangerous and selfish and horrible single women are. This risk of women not reproducing to continue the species (or a very specific portion of the species) seems to threaten people at all levels and at all times and for all reasons.

What I really enjoyed about Traister's approach is that she looked at single women from many perspectives. She talks about how life for women in cities is different than life in suburban and rural areas, about female friendship, about women living on their own. She talks about why women choose to stay single (for work, money, independence, choice), not only rich women but also poor women. She talks about how people assume single women live hugely promiscuous lives when the reality is usually quite different, single moms, and the families that women create for themselves when they are not married.

Right at the start, Traister admits that she has an urban, educated, white slant to her book. That said, she does make some effort to meet and talk to people who have had different experiences. She also cites a lot of evidence about people from many walks of life.

I have been single my whole life, and I have many single female friends, and this book really resonated with me. Contrary to what many people think, I do not spend my nights desperately wishing there was a man in my life (though admittedly, there are some times, usually during engagement parties and weddings and showers, when I do). I also don't go out with dozens of guys a year. I'm not a shrew who is unkind to people (though I admit that I can be quite unkind to people I dislike strongly), and I'm not an anti-social, awkward person who stays at home every night with her books and wine (though I do enjoy evenings by myself just as much as I enjoy spending time with other people). I would be happy to find a guy that I really love and get married, but if I do not meet one, I am pretty sure I will be happy and fulfilled in my life. Except, of course, for everyone always wondering why I am single and what's wrong with me and when I'll finally stop being so picky.

Rebecca Traister understands all of this, and I felt so validated by this book. I think many people would. I love how Traister sets up historical "norms" as completely outside the norm. For example, so many people look back on women getting married young and then having children as being the basis of so much economic growth and prosperity. But even through history, many women have had to work outside the home to make ends meet. And people make it seem as though women are being selfish and thinking only of themselves and putting the world at great risk. But really, they're just making reasonable decisions for themselves, and people who complain about what they're doing should just get over themselves.

This book is not exhaustive by any means, but I don't think Traister is trying to be exhaustive. She shares anecdotes about herself and from her friends, she tells us about the choices women have made through history and now, and what some of the numbers behind the trends mean. I think this book would be a fantastic companion to Gail Collins' books about women in America and the long, winding path that the women's movement has taken. Those books (referenced below) give a bit more breadth to the history whereas Traister's book has a personal and more "everyday woman" feel.

I've been reading a ton of non-fiction lately! Sorry for all the heavy subject reviews. Though really, this book is not heavy by any means - it's a very informative read, and I am glad to add it to my list of books that are refreshing and kind to women who make choices in life that not everyone understands.

Want to dig deeper on this subject? Here are a few links:

Shorter reads -

"On Spinsters," by Briallen Hopper, which is a review of a different book but makes fantastic points

"We Just Can't Handle Diversity," by Lisa Burrell, about how we all have biases and should acknowledge them instead of pretending we are totally objective about stuff

Long reads -

America's Women and When Everything Changed, by Gail Collins; I love these books about the history of women's rights and empowerment in America

Delusions of Gender, by Cordelia Fine; also absolutely amazing

Have a listen -

The Lady Vanishes episode of the Revisionist History podcast

Watch -

"We Should All be Feminists" TEDx video by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Labels:

america,

audiobook,

contemporary,

history,

non-fiction,

women

Monday, November 28, 2016

"There's more hunger in the world than love." - Monstress, Volume 1

In case you thought I only reviewed books about gloom and doom in America, DON'T WORRY. I also review books about gloom and doom in fantasy worlds! And Monstress, by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda, is a SUUUUUUUUPER good fantasy comic about gloom and doom.

I had never heard of Monstress before. I went to an indie bookstore for Small Business Saturday, and after we finished at the bookstore, my brother-in-law asked if we could go to a local comic bookstore, too. I said yes. I admit that I usually find comic bookstores quite intimidating, but the people at the one I went to were so nice! And they had this wall of best-selling comics, and it thrilled me to see how many of those best-sellers were ones that featured women. So of course, I felt the need to support both the indie store and female empowerment, and I purchased this book.

I don't know if I would have picked up Monstress if I had known how violent it is. Or how many dark subjects it tackles. But I'm so glad I didn't know those things and picked it up because it was SO GOOD!

(I hope that you are not the same as I am and that knowing the book is violent and dark will not drive you away from it, because that would be a mistake.)

Monstress is about many things, and I admit that I am vague on a lot of the details because it was also a bit confusing. But it doesn't really matter because it is amazing. The artwork is absolutely stunning, and brings to life a world that is complicated and can be difficult to grasp. Takeda puts a huge amount of detail into each panel. The dark color scheme she uses perfectly captures a world in the midst of an endless war. The rich detail in the panels shows the level of sophistication that the civilizations have reached, and the trade-offs between culture and war (and how one can often drive the other). The characters are all beautifully drawn, including a SERIOUSLY ADORABLE little fox named Kippa. Honestly, I feel like a lot of people will judge me for this, but I generally don't find animals that fascinating. Like, I know that puppies and kittens are sweet and cute, and I like looking at them sometimes, too, but I don't get squealy and excited or feel the need to pet them. But Kippa just stole my heart, mostly because of how vulnerable and sweet she was, and how she would hold her tail for security like a blanket. It's a little strange at first to see these doll-like faces (Kippa is not the only one with the perfect, adorable face) on such fierce characters, but hey, heroines come in all forms.

The artwork is great, but when you combine it with the story and the characters, the whole effect is quite pleasing.

I cannot believe I have gotten this far in my review without mentioning that this comic series is all about women. There was probably one main male character in this story (and possibly a male cat, but I'm not sure of the cat's gender). All the "good guys," all the "bad guys" - none of them are guys at all! And it's not a story that's obviously about women the way Lumberjanes is. (Though being obviously about women is totally fine, too! I was just making a comparison in that Lumberjanes is more vocally about women and the role of women vs Monstress is about the story and features women and the fact that it features women is the statement.)

I used to read a lot of epic fantasy, the multi-volume, 500+-page per volume variety that focused a lot on building a world and a lot on sharing that world's history and a lot on character development. I would say that Liu is a pretty amazing epic fantasy storyteller. She populates her world with a complex group of characters, none of whom have clear motivations or loyalties or goals (except the adorable Kippa! She's perfect in every way!). The main character is Maika, who is clearly very, very powerful but who also has a monster living inside her. Maika is trying to learn more about her past and who she is, but she has blackout moments when she must feed this monster inside of her. (With, er, people.) She tries to fight it, but, well, it's a monster (artistically rendered as a lot of tentacles and eyes), and that's hard work.

The monster at first seems like a straightforward villain, but as you get deeper into the story, you realize the monster also is confused and unsure of what to do. Maika works hard to make the right decisions for herself, and the monster works hard to make the right decisions for itself, but the two have to work together to do what is best for both of them. Hopefully, anyway, as no one really knows what is the best course of action. Even at the end of this book, it's unclear whether Maika is being hunted so that people can harness her power or so that she can be killed.

I mentioned a long, on-going war. There is one, and it's about one race exploiting another race for power. This seems pretty standard for a lot of fantasy and science fiction novels, but it's still a very important storyline to drill into people's heads, and I liked Liu's take on it. She has a lot here to develop and nurture over the course of the next several volumes, and I can see this becoming a very rich and rewarding series.

I had never heard of Monstress before. I went to an indie bookstore for Small Business Saturday, and after we finished at the bookstore, my brother-in-law asked if we could go to a local comic bookstore, too. I said yes. I admit that I usually find comic bookstores quite intimidating, but the people at the one I went to were so nice! And they had this wall of best-selling comics, and it thrilled me to see how many of those best-sellers were ones that featured women. So of course, I felt the need to support both the indie store and female empowerment, and I purchased this book.

I don't know if I would have picked up Monstress if I had known how violent it is. Or how many dark subjects it tackles. But I'm so glad I didn't know those things and picked it up because it was SO GOOD!

(I hope that you are not the same as I am and that knowing the book is violent and dark will not drive you away from it, because that would be a mistake.)

Monstress is about many things, and I admit that I am vague on a lot of the details because it was also a bit confusing. But it doesn't really matter because it is amazing. The artwork is absolutely stunning, and brings to life a world that is complicated and can be difficult to grasp. Takeda puts a huge amount of detail into each panel. The dark color scheme she uses perfectly captures a world in the midst of an endless war. The rich detail in the panels shows the level of sophistication that the civilizations have reached, and the trade-offs between culture and war (and how one can often drive the other). The characters are all beautifully drawn, including a SERIOUSLY ADORABLE little fox named Kippa. Honestly, I feel like a lot of people will judge me for this, but I generally don't find animals that fascinating. Like, I know that puppies and kittens are sweet and cute, and I like looking at them sometimes, too, but I don't get squealy and excited or feel the need to pet them. But Kippa just stole my heart, mostly because of how vulnerable and sweet she was, and how she would hold her tail for security like a blanket. It's a little strange at first to see these doll-like faces (Kippa is not the only one with the perfect, adorable face) on such fierce characters, but hey, heroines come in all forms.

The artwork is great, but when you combine it with the story and the characters, the whole effect is quite pleasing.

I cannot believe I have gotten this far in my review without mentioning that this comic series is all about women. There was probably one main male character in this story (and possibly a male cat, but I'm not sure of the cat's gender). All the "good guys," all the "bad guys" - none of them are guys at all! And it's not a story that's obviously about women the way Lumberjanes is. (Though being obviously about women is totally fine, too! I was just making a comparison in that Lumberjanes is more vocally about women and the role of women vs Monstress is about the story and features women and the fact that it features women is the statement.)

I used to read a lot of epic fantasy, the multi-volume, 500+-page per volume variety that focused a lot on building a world and a lot on sharing that world's history and a lot on character development. I would say that Liu is a pretty amazing epic fantasy storyteller. She populates her world with a complex group of characters, none of whom have clear motivations or loyalties or goals (except the adorable Kippa! She's perfect in every way!). The main character is Maika, who is clearly very, very powerful but who also has a monster living inside her. Maika is trying to learn more about her past and who she is, but she has blackout moments when she must feed this monster inside of her. (With, er, people.) She tries to fight it, but, well, it's a monster (artistically rendered as a lot of tentacles and eyes), and that's hard work.

The monster at first seems like a straightforward villain, but as you get deeper into the story, you realize the monster also is confused and unsure of what to do. Maika works hard to make the right decisions for herself, and the monster works hard to make the right decisions for itself, but the two have to work together to do what is best for both of them. Hopefully, anyway, as no one really knows what is the best course of action. Even at the end of this book, it's unclear whether Maika is being hunted so that people can harness her power or so that she can be killed.

I mentioned a long, on-going war. There is one, and it's about one race exploiting another race for power. This seems pretty standard for a lot of fantasy and science fiction novels, but it's still a very important storyline to drill into people's heads, and I liked Liu's take on it. She has a lot here to develop and nurture over the course of the next several volumes, and I can see this becoming a very rich and rewarding series.

Thursday, May 12, 2016

Be kind to yourself

When I was younger, I really hated the word "nice" as a descriptor of people. I thought nice meant boring. I hoped that no one would ever use "nice" as the first word to describe me. I was so much more! Fun and witty and opinionated and all the rest. I wasn't boring. And I didn't want to be thought of as just nice.

I'm in my early 30s now, and my perspective has completely changed. I love nice people. I would be thrilled if someone were to describe me as "just a really, really good person." I can't think of any personality trait that I find more attractive than kindness, except perhaps a sense of humor that is similar to mine.

Sara Eckel's book, It's Not You: 27 (Wrong) Reasons You're Single, is a kind book. It is a longer version of her excellent, very popular Modern Love essay in the New York Times. It's about being kind to yourself, which can often be very difficult, especially if you are a single woman in your 30s or 40s. Inevitably, people think there is something wrong with you. Eckel does not. She says that if you're single, it's not because something's wrong with you. It's because finding someone is hard. It takes a lot of luck. It's about timing. And if it happens, that's great. But if it doesn't, it's not your fault. You are no less worthy of love than other people are.

So many things that Eckel brings up here as the reasons why women are single (you're too picky, you're too intimidating, you're too available, you need more practice, you aren't playing the game, etc.) are things that have been said to me by well-meaning friends and pretty much complete strangers. Eckel takes 27 of the most common reasons self-help books and well-meaning friends tell you that you're single and refutes them. She tells you why vulnerability is a good thing, why you should stand up for yourself. She is just that really wonderful girlfriend who listens to you and doesn't judge you but instead gives you support and a really excellent hug.

I've been single for pretty much my entire life. I have done so many of the things Eckel mentions here. She talks about all the projects and tasks single women take up, trying to make themselves more well-rounded, better, worthier people for relationships. They exercise, they learn to cook, they host dinner parties, they volunteer in their communities, they travel alone, they work really hard to make new friends and keep long-established friendships alive.

And it's true. I am in the best shape of my life right now, I have more friends than I've ever had before, I make sure that I have a full calendar (though I will never use the word "busy" to describe myself as I hate that word), and I put myself out there far more often, and in ways that make me quite a bit more uncomfortable, than I ever would have thought possible even 5 years ago. Being single has made me into a better person, even if being single can be really hard sometimes. But has it made me more "worthy" of finding someone? No.

Eckel talks a lot about self-compassion and Buddhist teachings (though she does not consider herself a Buddhist). This is an idea I have been thinking about quite a bit over the past several months, mostly because I think so many people are kind to others but are not kind to themselves. We do not trust ourselves, we do not give ourselves credit for going out there and giving it the ole college try, we assume there must be something wrong with us. Eckel references a TED Talk by Brene Brown that I looked up after finishing the book. It's about the power of vulnerability, and it is excellent. Brown says, yes, it's hard to make yourself vulnerable. It makes you feel weak, it makes you feel exposed, and it can be horrible when it doesn't go well. But... making yourself vulnerable also opens you up to richer, more wonderful relationships with people. It gives people the opportunity to be vulnerable with you, too. You learn more about someone. Your friendship deepens. You are kinder, gentler, more forgiving. They are, too. And it's worth it. "The people who have a strong sense of love and belonging believe they are worthy of love and belonging. That's it."

Eckel also talks about the whole "ice queen" idea - that if a woman really wants to get a man's attention, she should basically ignore him and pretend she doesn't care about him, because if he realizes she cares, then he'll leave. Of every piece of dating advice out there, this one always comes up. Don't show too much interest. Play the game. Don't respond to his text for like, 8 hours, even though everyone knows you saw the text as soon as it was sent because what are the chances you don't have your phone with you?

I would say this is always the one I struggle with the most because I think it's really bad form and quite rude not to respond to someone who contacts you. I also have very little patience in spending time with people I don't like when I could spend time with people I do like. If I like you, I will make time for you. If I don't, I won't. The idea of not making time for someone that I like is just ridiculous to me. The idea of treating someone I really like unkindly is also very hard to take. As Eckel says,

And that's why I think this book was so great. It was not at all self-help-y, it was not about finding ways to find guys, it was not about anything except feeling good about yourself. And that means a lot.

One of Eckel's single friends, when asked what she wanted in a man (because some people thought she was too picky, and other people thought she just didn't know a good thing when she had it), said something that I think is pretty much perfect, and will be my criteria going forward:

I'm in my early 30s now, and my perspective has completely changed. I love nice people. I would be thrilled if someone were to describe me as "just a really, really good person." I can't think of any personality trait that I find more attractive than kindness, except perhaps a sense of humor that is similar to mine.

Sara Eckel's book, It's Not You: 27 (Wrong) Reasons You're Single, is a kind book. It is a longer version of her excellent, very popular Modern Love essay in the New York Times. It's about being kind to yourself, which can often be very difficult, especially if you are a single woman in your 30s or 40s. Inevitably, people think there is something wrong with you. Eckel does not. She says that if you're single, it's not because something's wrong with you. It's because finding someone is hard. It takes a lot of luck. It's about timing. And if it happens, that's great. But if it doesn't, it's not your fault. You are no less worthy of love than other people are.

So many things that Eckel brings up here as the reasons why women are single (you're too picky, you're too intimidating, you're too available, you need more practice, you aren't playing the game, etc.) are things that have been said to me by well-meaning friends and pretty much complete strangers. Eckel takes 27 of the most common reasons self-help books and well-meaning friends tell you that you're single and refutes them. She tells you why vulnerability is a good thing, why you should stand up for yourself. She is just that really wonderful girlfriend who listens to you and doesn't judge you but instead gives you support and a really excellent hug.

I've been single for pretty much my entire life. I have done so many of the things Eckel mentions here. She talks about all the projects and tasks single women take up, trying to make themselves more well-rounded, better, worthier people for relationships. They exercise, they learn to cook, they host dinner parties, they volunteer in their communities, they travel alone, they work really hard to make new friends and keep long-established friendships alive.

And it's true. I am in the best shape of my life right now, I have more friends than I've ever had before, I make sure that I have a full calendar (though I will never use the word "busy" to describe myself as I hate that word), and I put myself out there far more often, and in ways that make me quite a bit more uncomfortable, than I ever would have thought possible even 5 years ago. Being single has made me into a better person, even if being single can be really hard sometimes. But has it made me more "worthy" of finding someone? No.